August 12, 2014

Admit One: Attorney Wins By Failing to Effectively Communicate to Jury

A complex case goes to trial. The parties, witnesses, jurors and lawyers endure weeks of frantic preparation, arguments and witness testimony. Near the end, the defense lawyer faces the jury to deliver his closing argument. He does not want to let his client down by failing to effectively communicate. However, while articulating his client’s position, he admits a key fact.

A complex case goes to trial. The parties, witnesses, jurors and lawyers endure weeks of frantic preparation, arguments and witness testimony. Near the end, the defense lawyer faces the jury to deliver his closing argument. He does not want to let his client down by failing to effectively communicate. However, while articulating his client’s position, he admits a key fact.

Perhaps his opponent writes this judicial admission down on a legal pad, shifts back in his chair, smiles modestly and relaxes muscles that have been tense for weeks. Defense counsel concludes his argument. The Judge reads instructions to the jurors. After deliberation, the jury returns with a verdict completely in favor of the defendants, contrary to the admission! Surely relief from the verdict is available, at least on the point of the judicial admission? What amount of jury supervision can attorneys and their clients expect from a trial judge in similar situations?

In June 2013, William Nickerson, a Senior Federal Judge in Maryland, faced a similar situation. He ruled that the plaintiff’s lawyer’s failure to move to revise the jury instructions after the closing arguments rendered the defense lawyer’s admission not binding. On August 5, 2014, Federal Court of Appeals upheld this decision. (This appeals court has authority to also hear appeals from federal trial courts in Virginia) This case illustrates how attention to detail and quick decision-making in jury trials challenges even seasoned litigators. An attorney and client should not bring a lawsuit unless they are willing to prepare to take the case to trial. They must also have sufficient risk tolerance to permit the result to be determined by disinterested judges and jurors.

Class Action Against Long & Foster, Wells Fargo Bank & Prosperity Mortgage:

In the facts of Judge Nickerson’s case, Denise Minter and others used Long & Foster to help them purchase homes. Long & Foster has a joint venture with Wells Fargo Bank called Prosperity Mortgage. Prosperity lends home loans on a wholesale line of credit provided by Wells Fargo. Some of Prosperity’s offices are next door to Long & Foster’s. Ms. Minter used Prosperity to obtain a home loan.

This case caught my attention because Long & Foster has a large market share in residential real estate in Northern Virginia. This case held many business relationships in the balance. On a personal note, Long & Foster has been the listing or buyers agent for every real estate transaction I have been personally involved in. Long & Foster has some agents that I would use again (or refer to others) and some that I would not. I’ve never used Prosperity Mortgage.

Ms. Minter and other common customers (but not me) became dissatisfied with the services of Long & Foster and Prosperity and filed a class action lawsuit. They alleged that Wells Fargo and Long & Foster created Prosperity as a “sham” in order to skirt legal prohibitions on “kickbacks” obtained in settlements that were inadequately disclosed to the consumers. They brought their class action under the Federal Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act.

The trial court certified the plaintiffs class action except for certain claims that could only be brought if Prosperity customers were actually referred by Long & Foster. Those potential claims were set aside for a future, separate trial. In order to get a trial on those other claims, the court required a factual finding at the first trial that Long & Foster referred the plaintiffs to Prosperity.

The jury received extensive evidence in the 17 day trial. Near the end, Long & Foster lawyer Jay Veron presented a closing argument, including, “I think the only thing I agree way (sic) for sure is that Long & Foster did refer the named plaintiffs to Prosperity. There’s no dispute about that.” The jury received predetermined instructions from the Judge. These included Verdict Question No. 3:

Have Plaintiffs proved, by a preponderance of the evidence, that Long & Foster Real Estate Inc., referred or affirmatively influenced the Plaintiffs to use Prosperity Mortgage Company for the provision of settlement services.

This question was almost identical to one proposed by the Plaintiffs’ lawyers. After deliberation, the jury answered “No” to Question No. 3.

The consumers’ attorneys moved the court to set aside the jury’s verdict and order a new trial. Counsel argued that Long & Foster’s factual concession during the closing arguments constituted a “judicial admission” that bound Long & Foster in the case.

Judicial Admissions:

What is a Judicial Admission? The Circuit Court opinion explains that under federal evidence law, they are a representations by a party or their agent that are conclusive in the court case unless the judge allows them to be withdrawn. They can occur in pleadings, discovery or at trial. The are not limited to written communications. Judicial Admissions include intentional and unambiguous waivers that release the opposing party from its burden to prove the facts necessary to establish the waived conclusion of law.

For these reasons, lawyers routinely counsel clients with strategies designed to avoid making undesired admissions regarding issues in controversy. Even if an admission does not achieve binding effect, it remains fertile ground for cross-examination and falls outside the protection of a hearsay objection.

Mr. Veron’s decision to tell the jury that there was no dispute whether Long & Foster referred the plaintiffs to Prosperity was significant. Perhaps he thought that the jury would think this anyway and that he needed to concede this in order to maintain credibility. The jury either wasn’t listening, didn’t understand or believe him. In many trials, the jurors’ least favorite parts are when lawyers are talking. Veron achieved a complete victory by failing to effectively communicate what he was trying to say to the jury. In the words of the prison warden in the 1967 film, Cool Hand Luke, “What we got here is a failure to communicate.” In a 17 day trial, there is bound to be some mis-communication.

Post-Trial Motions:

The plaintiffs’ attorney needed the Court to accept Mr. Veron’s admission for the consumers to get another trial on separate, related claims predicated on that admitted fact. Plaintiff’s counsel moved to have the jury verdict set aside as contrary to the admission and the evidence. The Judge Nickerson rejected the motion for a new trial, explaining that:

Trial advocacy involves knowing when to interject with objections and motions and when to allow the case to simply flow on. In this 17 day trial, undoubtedly there were many objections and motions made by both sides calculated to steer the outcome. However, a trial attorney cannot object or make a motion whenever his opponent tries to accomplish anything. Judges and juries become weary of frequent interruptions of the flow of testimony. When Long & Foster’s attorney made this admission to the jury, the consumers’ lawyer may have thought: “Finally, something unobjectionable and consistent with what I have been saying for the past 17 days.” Unfortunately, by not moving to have the jury instructions and verdict forms changed to reflect this stipulated fact, the jury was permitted to decide it. The jury probably was not aware that there was a whole separate trial that could be precluded based on that factual finding. In the end, the joint venture known as Prosperity Mortgage survived this class action assault.

This Minter trial has several takeaways:

- Just because the parties agree doesn’t mean the jury will.

- Juries have been known to ignore things lawyers say.

- Never give up! Always listen for things that require immediate action to avoid waiver. (This does not mean object to each and every thing.)

- Going to trial, especially with a jury, requires risk tolerance.

- When a problem that requires litigation solution, trial experience counts.

- If an attorney prevails because he fails to communicate what he wants to say, then that is still a happy day for him, his law firm, and his client.

I sympathize for the class action plaintiffs lawyer. He showed opposing counsel respect by assuming that the jury would listen to the judicial admission and decide their verdict in accordance with the fact not in controversy. He also exhibited respect for the jurors, whom he assumed would draw the conclusion based on the arguments and weight of the evidence. He also respected the judge’s desire not to have yet another matter to quickly rule on.

This case illustrates that any system of justice administered by humans will run the risk of inscrutable results. A qualified trial attorney serves clients by managing these risks arising from unresolved legal disputes. This is accomplished through commitment to client service, zealously pursuing the clearest path to victory while exploring reasonable settlement opportunities.

This is Part One in a series of blog posts about the Minter v. Prosperity Mortgage, et al. case. Part Two is about certain challenges to credibility made in closing arguments.

Case Citations:

Minter v. Wells Fargo Bank, No. 07-3442 (Dist. Md. Aug. 28, 2013)(Nickerson, J.).

Minter v. Wells Fargo Bank, 762 F.3d 339 (4th Cir. 2014).

Photo Credit: Paul L Dineen via photopin cc

July 24, 2014

Tenancy by the Entirety and Creditor Recourse to Marital Real Estate

Last week I focused on first-time home buyers and new opportunities for state tax-exempt estate planning. This week’s post continues on the theme of family. Spouses who own Virginia property together may enjoy special protections against the claims of their individual creditors. This special form of ownership is called “Tenancy by the Entirety.” For this to arise, the husband and wife must own in unity of (a) time, (b) title, (c) interest and (d) possession. These requirements may be inferred if the deed specifically conveys to the husband and wife by tenancy by the entirety or with an intent to create a right of survivorship.

As far as creditors are concerned, the couple jointly owns an undivided 100% interest. This ancient doctrine continues to be applied by Virginia courts in contemporary real estate controversies. This post focuses on ways creditors may succeed in spite of this manner of holding title:

- Joint Consent. Neither spouse may sever the tenancy by his sole act. Likewise, one spouse cannot convey the property unilaterally. This becomes significant if one spouse attempts to mortgage the property without the consent of the other. However, the spouses may cause the termination of the tenancy by the entirety ownership or jointly liability for a lien or judgment. For example, when the owners take out a mortgage, if properly perfected, that lien will persevere against acts of divorce and/or bankruptcy unless exceptions apply. Also, if only one spouse files for bankruptcy, the tenancy by the entirety property remains outside of the Bankruptcy Estate.

- Divorce. Completion of a divorce transforms a tenancy by the entirety into a tenancy in common, the ordinary form of co-ownership. In equitable distribution, a Judge has considerable latitude in dividing up marital property.

- Death. Because of the right of survivorship, no transfer of title occurs to the survivor upon the death of a spouse. Upon death, the interest of the surviving spouse converts from a tenancy by the entirety to a sole ownership interest. At that time, the property then becomes subject to creditor claims.

- Fraud. If the husband and wife attempt to work a fraud on a creditor by improper use of a tenancy by the entirety conveyance, it is unlikely that the court would permit the fraud. However, if the couple sells real estate held in a tenancy by the entirety, the proceeds of that sale automatically also enjoy the same status as the real estate, unless there is an agreement to the contrary. A transfer from the husband and wife holding in tenancy by the entirety to the sole name of one of the spouses does not subject those funds to the claims of the other spouse’s creditors.

The gist of tenancy by the entirety flows intuitively from the legal understanding of marriage. It possesses a seemingly “magical” quality when it comes to protecting against many individual creditor claims. However, it can be difficult applying the doctrine to a family’s individual circumstances. If you have questions about Tenancy by the Entirety, whether as a spouse or a creditor, contact a qualified attorney.

Court Opinions:

In Re Eidson, 481 B.R. 380 (Bankr. E.D. Va. 2012) (interpreting Va. law).

Alvarez v. HSBC Bank USA, 733 F.3d 136 (4th Cir. 2013) (interpreting Md. law).

U.S. v. Parr, File No. 3:10-cv-061 (W.D. Va. Oct. 6, 2011) (Moon, J.) (interpreting Va. law).

In Re Bradby, 455 B.R. 476 (Bankr. E.D. Va. 2011) (interpreting Va. law).

In Re Nagel, 298 B.R. 582 (Bankr. E.D. Va. 2003).

July 2, 2014

Attorneys Fees for Rescission of Contracts Obtained by Fraud

In lawsuits over real estate, attorney’s fees awards are a frequent topic of conversation. In Virginia, unless there is a statute or contract to the contrary, a court may not award attorney’s fees to the prevailing party. This general rule provides an incentive to the public to make reasonable efforts to conduct their own affairs to avoid unnecessary legal disputes. An exception to the general rule provides a judge with the discretion to award attorney’s fees in favor of a victim of fraud who prevails in court. Effective July 1, 2014, a new act of the General Assembly allows courts greater discretion to award attorneys fees for rescission of contracts obtained by fraud and undue influence. The text reads as follows:

This new statute narrowly applies to fraud in the inducement and undue influence claims requesting as a remedy rescission of a written instrument. I expect this new attorney’s fees statute to become a powerful tool in litigation over many real estate matters.

- Obtaining Approval of Written Instruments by Misconduct. This new statute does not focus on the manner or sufficiency of how obligations under a contract or deed are performed. Instead, it concerns remedies where one party obtains the other’s consent on a written instrument by material, knowing misrepresentations made to induce the party to sign (fraud) or abusive behavior serving to overpower the will of a mentally impaired person (undue influence). Fraud and undue influence are usually hard to prove. There are strong presumptions that individuals are (a) in possession of their faculties, (b) are reasonably circumspect about the deals and transfers they make and (c) read documents before signing them. This new statute does not allow for fees absent clear & convincing proof of the underlying wrong. Tough row to hoe.

- Undoing Deals Predicated on Fraud or Undue Influence: This new statute doesn’t help plaintiffs who only want damages or some other relief. The lawsuit must be to rescind the deed or contract that was procured by the fraud or undue influence. Rescission is a traditional remedy for fraud and undue influence, and it seeks to “undo the deal” and put the parties back in the positions they were in prior to the consummation of the transaction. This statute should give defendants added incentive to settle disputes by rescission where a fraud in the inducement or undue influence case is likely to prevail.

- Reasonableness of the Attorney’s Fees Award: When these circumstances are met, the Court has discretion to award reasonable attorney’s fees. Note that the statute does not require that fees be awarded in every rescission case. Under these provisions, on appeal the judge’s attorney’s fees award or lack thereof will be reviewed according to the Virginia legal standard for reasonableness of attorney’s fees.

Prior to enactment of Va Code Sect. 8.01-221.2, defrauded parties had to meet a heightened standard in order to get attorney’s fees. In 1999, the Supreme Court of Virginia held in the Bershader case that even if there is no statute or contract provision, a judge may award attorney’s fees to the victim of fraud. However, in Bershader the Court found that the defendants engaged in “callous, deliberate, deceitful acts . . . described as a pattern of misconduct. . .” The Court also found that the award was justified because otherwise the victims’ victory would have been “hollow” because of the great expense of taking the case through trial. The circumstances cited by the Court in justifying the attorney’s fees award in Bershader show that the remedy was closer to a form of litigation sanction than a mere award of fees. Bershader addressed an extraordinary set of circumstances. Trial courts have been reluctant to award attorney’s fees under Berschader because it did not define a clear standard.

The new statutory enactment removes the added burden to the plaintiff of showing extraordinary contentiousness and callousness or other circumstances appropriate on a litigation sanctions motion. It is hard enough to prove fraud or undue influence by clear and convincing evidence, and then show reasonableness of attorney’s fees. Why should the plaintiff be forced to prove callousness and a threat of a “hollow victory” if fraud has already been proven and the court is bound by a reasonableness standard in awarding fees? The old rule placed a standard for awarding attorney’s fees in fraud cases to a heightened standard comparable to the one available for imposition of litigation sanctions. Va. Code 8.01-221.2 permits attorney’s fees in a rescission case without transforming every dispute in which deception is alleged into a sanctions case.

case citation: Prospect Development Co. v. Bershader, 258 Va. 75, 515 S.E.2d 291 (1999).

photo credit: taberandrew via photopin cc (photo is a city block in Richmond, Virginia and does not illustrate any of the facts or circumstances described in this blog post)

May 29, 2014

What is a Revocable Transfer on Death Deed?

On May 20th I attended the 32nd Annual Real Estate Practice Seminar sponsored by the Virginia Law Foundation. Attorney Jim Cox gave a presentation entitled, Affecting Real Estate at Death: the Virginia Real Property Transfer on Death Act. Jim Cox presented an overview of this new estate planning tool that went into effect July 1, 2013.

Use of Transfer on Death (“TOD”) beneficiary designations for depository and retirement accounts is widespread. This 2013 Act allows owners of real estate to make TOD designations by recording a Revocable Transfer on Death Deed in the public land records.

The introduction of TOD Deeds is of interest to anyone involved in estate planning or real estate settlements. The following are 8 key aspects of this development in Virginia law:

- Not Really a “Deed.” A normal deed conveys an interest in real property to the grantee. A TOD Deed is a will substitute that becomes effective only if properly recorded and not revoked prior to death. The Act’s description of this instrument as a “deed” will likely be a source of confusion.

- Formal Requirements. A TOD Deed must meet the formal requirements of the statute in order to effect the intent of the owner. It must contain granting language (a.k.a. words of conveyance) appropriate for a TOD Deed. It is not effective unless recorded in land records prior to the death of the transferor. The statute contains an optional TOD Deed form. Due to the formal requirements, I cannot image advising someone to do one of these without a qualified attorney.

- Beneficiary Does Not Need to be Notified. Although a TOD Deed becomes public when filed, the transferor does not need to notify the recipient. The beneficiary may not learn about the designation until after the transferor’s death. At some point, the local government will change the addressee on the property tax bills.

- Freely Revocable. The transferor can revoke the TOD designation at any time prior to death. In fact, a TOD Deed cannot be made irrevocable. A revocation instrument must be recorded in land records.

- Unintended Title Problems. The Act takes pains to avoid creating title defects on the transferor’s title prior to death.

- Can be Disclaimed. The beneficiary can disclaim the transfer after the death of the transferor.

- Subject to Liens. Recording a TOD Deed does not trigger a due-on-sale clause in a mortgage. At the date of death, the beneficiary’s interest is subject to any enforceable liens on the property.

- Creditor Claims & Administration Costs. The beneficiary’s interest in the property is subject to any general claims of the transferor’s creditors or the expenses of the estate administration. Such claims may attach up to one year after the date of the transferor’s death. For this reason, the TOD beneficiary’s interest in the property or the proceeds of its sale will be uncertain until that 12 month period expires. However, taxing authorities, insurance companies, HOA’s and banks will expect payment prior to the end of those 12 months.

Each family has unique estate planning needs. The Va. Real Property TOD Act is a new gadget in the toolbox for crafting a plan that addresses individual desires and circumstances. Combining TOD Deeds with other estate planning tools such as wills and trusts requires careful integration to avoid unintended consequences. Estate planning and real estate practitioners will overcome any initial reluctance to use of TOD Deeds as they become subject to the test of time.

If you learn that you are the beneficiary of a TOD deed and are uncertain as to your rights and responsibilities with respect to the property, contact an experienced real estate attorney.

May 16, 2014

What Difference Does It Make? Technical Breaches By Banks in Foreclosure

If a bank makes a technical error in the foreclosure process, what difference does it make? This blog post explores new legal developments regarding the materiality of breaches of mortgage documents. Residential foreclosure is a dramatic remedy. A lender extended a large sum of credit. Borrowers stretch themselves to make a down payment, monthly payments, repairs, association dues, taxes, etc. If financial hardships present obstacles to borrowers making payments, usually they will do what they can to keep their home.

In order to foreclose, lenders must navigate a complex web of provisions in the loan documents and relevant law. Note holders frequently commit errors in processing a payment default through a foreclosure sale. Sometimes these breaches are flagrant, such as foreclosing on a property to which that lender does not hold a lien. Usually they are less significant in the prejudice to the borrower’s rights. For example, written notices may not follow contract provisions or regulations verbatim, or a notice went out a day late or by regular mail instead of certified mail. Regardless of their significance, these rules were either willingly adopted by the parties or represent public policies reduced to law.

When homeowners challenge foreclosures in Court, lenders frequently argue in defense that the errors committed by the bank in the foreclosure process are not material. One could express this argument in another way by quoting the title lyric to British band The Smiths’ 1984 song, “What difference does it make?” The lenders typically highlight that the borrowers fell behind on their payments, did not come current, and do not have a present ability to come current on their loans. Borrowers face an uphill battle convincing judges to set aside or block foreclosure trustee sales or award money damages for non-material breaches. However, last month, two new court opinions illustrate a trend towards allowing remedies to homeowners for technical breaches. A relatively small award of money damages may not give homeowners their house back, but it may provide some consolation to the borrower and provide an incentive to mortgage investors, servicers and foreclosure trustees to strengthen their compliance programs.

When homeowners challenge foreclosures in Court, lenders frequently argue in defense that the errors committed by the bank in the foreclosure process are not material. One could express this argument in another way by quoting the title lyric to British band The Smiths’ 1984 song, “What difference does it make?” The lenders typically highlight that the borrowers fell behind on their payments, did not come current, and do not have a present ability to come current on their loans. Borrowers face an uphill battle convincing judges to set aside or block foreclosure trustee sales or award money damages for non-material breaches. However, last month, two new court opinions illustrate a trend towards allowing remedies to homeowners for technical breaches. A relatively small award of money damages may not give homeowners their house back, but it may provide some consolation to the borrower and provide an incentive to mortgage investors, servicers and foreclosure trustees to strengthen their compliance programs.

Content of Written Notices Required by Mortgage Documents:

On June 13, 2010, Wells Fargo Bank sent Bonnie Mayo a letter telling her he was in default on her mortgage on her Williamsburg residence. The letter indicated that if she failed to cure within 30 days, Wells Fargo would proceed with foreclosure. The letter informed her that, “[i]f foreclosure is initiated, you have the right to argue that you did keep your promises and agreements under the Mortgage Note and Mortgage, and to present any other defenses you may have.” However, the Mortgage required the lender to state in the written notice the borrower’s “right to reinstate after acceleration and right to bring a court action to assert the non-existence of a default or any other defense of Borrower to acceleration and sale.” Ms. Mayo’s notice did not include this language. She did not bring a lawsuit until after the date of the foreclosure sale.

In her post-foreclosure lawsuit, Mayo alleged (among other claims) that this breach entitled her to rescind the foreclosure and receive money damages. Wells Fargo moved to dismiss this claim on the grounds that the difference between the contractually required language and the actual letter was immaterial. In an April 11, 2014 opinion, Judge Raymond Jackson observed that just because a breach is non-material does not mean it is not a breach at all. He reached a conclusion contrary to a relatively recent opinion of another judge in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Virginia courts recognize claims to set aside foreclosure sales for “weighty” reasons but not “mere technical” grounds. Judge Jackson suggested that the bar may be higher for a homeowner to set aside a foreclosure sale after it occurs than to block it from happening in the first place. The Court declined to dismiss this claim on the sufficiency of the notices. Judge Jackson found that the materiality of this breach was a factual dispute requiring additional facts and argument to resolve.

A foreclosure is less susceptible to legally challenge after a subsequent purchaser goes to closing. Thus, the bank’s omission of language informing the borrower of her right to sue prior to the foreclosure carried a heightened potential for prejudice. Whether Ms. Mayo had a likelihood of prevailing in an earlier-filed lawsuit is a different story.

Failure to Conduct a Face-to-Face Meeting Prior to Foreclosure:

In 2002, Kim Squire King financed the purchase of a home in Norfolk, Virginia, with a Virginia Housing Development Authority mortgage. Her loan documents incorporated U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development regulations requiring a lender to make reasonable efforts to arrange a face-to-face interview with the borrower between default and foreclosure. Loss of employment caused King to go into default on her VHDA loan in March 2010. VHDA never offered King a face-to-face meeting. VHDA instituted foreclosure wherein the trustee sold King’s property to a third-party.

King filed a lawsuit seeking money damages and an order rescinding the foreclosure sale. The judge in Norfolk agreed with defense arguments that the error was not grounds to set aside the completed foreclosure or award compensatory damages. The court dismissed the lawsuit. Squire appealed to the Supreme Court of Virginia. The Justices upheld the dismissal of her request to set aside the completed foreclosure sale. The lawsuit failed to allege facts sufficient to show that the sale was fraudulent or grossly inadequate.The Supreme Court distinguished King’s situation from legal precedents where the borrower filed suit prior to the foreclosure. Surprisingly, the Court found that the trial judge erred in dismissing King’s claim for money damages arising out of the failure to arrange the face to face meeting. The Justices remanded the case to proceed on the damages issue.

When mortgage servicers and foreclosure trustees commit technical errors, what difference does it make? These new legal decisions show increasingly nuanced analysis of these particular issues. The materiality of the lender’s breach depends on a number of factors, including:

- The borrower’s apparent ability to reinstate the loan. If it is unlikely that the homeowner will get back on track, denying the bank foreclosure makes less sense.

- Did the borrower file suit before or after the foreclosure sale? A lawsuit can delay a foreclosure until the borrowers enforce their rights under the loan documents and incorporated regulations. However, unless the borrowers have a strategy to work-out the distressed loan or otherwise favorably dispose of the property, a pre-foreclosure lawsuit may only delay.

- The relationship between the technical error and the relief requested by the borrower. For example, if the loan documents require a notice to go out by certified mail and it only goes out by first class mail, but the borrower received it anyway, then there isn’t any prejudice.

- Money damages suffered by the borrower that arose out of the technical breach. Borrowers seek to keep their homes and to pay according to their abilities. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia and the Supreme Court of Virginia show an increasing willingness to hold lenders monetarily responsible for prejudicial lender breaches in the foreclosure process. A legal claim that partially offsets the lender’s judgment for the balance of the loan post-foreclosure may provide some consolation but may not avoid bankruptcy.

Discussed Case Opinions:

Mayo v. Wells Fargo Bank, No. 4:13-CV-163 (E.D.Va. Apr. 11, 2014)(Jackson, J.)

Squire v. Virginia Housing Development Authority, 287 Va. 507 (2014)(Powell, J.)

photo credit: Fabio Bruna via photopin cc

May 6, 2014

Mortgage Fraud Shifts Risk of Decrease in Value of Collateral in Sentencing

On March 5, 2014, I blogged about the oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court in U.S. v. Benjamin Robers, a criminal mortgage fraud sentencing appeal. At stake was how Courts should credit the sale of distressed property in calculating restitution awards. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit interpreted the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act to apply the sales price obtained by the bank selling the property post foreclosure as a partial “return” of the defrauded loan proceeds. Robers appealed, arguing that he was entitled to the Fair Market Value of the property at the time of the foreclosure auction. According to Robers, the mortgage investors should bear the risk of market fluctuations post-foreclosure because they control the disposition of the collateral. See Mar. 5, 2014, How Should Courts Determine Mortgage Fraud Restitution?

Yesterday, the Supreme Court affirmed the re-sale price approach in a unanimous decision. The Court observed that the perpetrators defrauded the victim banks out of the purchase money, not the real estate. The foreclosure process did not restore the “property” to the mortgage investors until liquidation at re-sale.

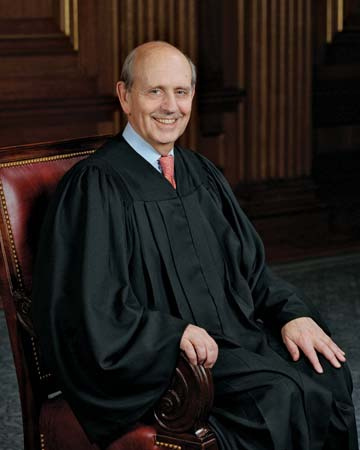

The Court focused on defense arguments that the real estate market, not Robers, caused the decrease in value of collateral between the time of the foreclosures and the subsequent bank sales. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote that:

Fluctuations in property values are common. Their existence (through not direction or amount) are foreseeable. And losses in part incurred through a decline in the value of collateral sold are directly related to an offender’s having obtained collateralized property through fraud.

Breyer distinguished “market fluctuations” from actions that could break the causal chain, such as a natural disaster or decision by the victim to gift the property or sell it to an affiliate for a nominal sum. See Lance Rogers, May 6, 2014, BNA U.S. Law Week, “Justices Clarify that Restitution ‘Offset’ is Gauged at Time Lender Sells Collateral.”

Falsified mortgage applications cause a lender to make a loan that it would not otherwise extend. A restitution award mirroring what the lender would receive in a civil deficiency judgment is inadequate. The defendant’s conduct opened the door for the Court to shift the risk of post-foreclosure market fluctuation from the bank to the borrower. Robers did not single-handedly render the local real estate market illiquid. However, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor mentions in her concurrence, real estate takes time to liquidate. These banks did not unreasonably delay the liquidation process. The Court opinion did not mention the prominent role of origination fraud in the subprime mortgage crisis. The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision strongly rejected defense arguments that downward “market fluctuations” severed the causal connection between the origination fraud and the depressed sales prices obtained by the lenders.

The Court did not discuss the original purchase prices for Robers’ two homes. In many mortgage fraud schemes, loan officers find “straw purchasers” such as Mr. Robers for sellers who agree to provide kickbacks on the inflated sales prices. See Mar. 15, 2009, Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, “Amid Subprime Rush, Swindlers Snatched $4 Million.” The perpetrators do not disclose these kickbacks to the lenders. The mortgage originators also receive origination fees from the lenders on the fraudulent closings. Under this arrangement, the purchase price will naturally reflect the highest sales price the bank’s appraiser will support. The bank is defrauded both by the fictitious qualifications of the borrower and the exaggerated sales prices.

U.S. v. Robers may result in stricter, more consistent restitution awards in mortgage fraud cases. I wonder how it will be applied in cases where the defendant presents stronger evidence that the victims acted unreasonably in liquidating the property. The opinion seems to leave discretion to District Courts to determine whether a bank’s conduct or omissions breaks the connection between the mortgage fraud and the sales price.

May 2, 2014

Sterling v. Stiviano: Spouse Sues Paramour Over Title to Property

Earlier this week, the National Basketball Association imposed a lifetime ban on Donald Sterling, owner of the Los Angeles Clippers. Adventuress Vanessa Stiviano recorded racist and demeaning statements made by Sterling about Basketball Hall of Famer Earvin “Magic” Johnson. The recordings subsequently leaked to the public.

In 1991, I watched the first NBA Finals for the first time. Magic Johnson led the Lakers against Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls. The 1991 Finals made me a basketball fan. Magic was one of my favorite professional athletes. The news about Don Sterling is offensive and bizarre. Why is this scandal happening?

On March 7, 2013, Sterling’s wife, Rochelle, filed a lawsuit against Ms. Stiviano. The lawsuit alleges that Stiviano seduced Don for money. According to Rochelle, Stiviano used marital funds to purchase a $1.8 Million dollar duplex home in Los Angeles in December 2013. Rochelle seeks a court order reforming the deed to identify herself and her husband as the proper owners.

The LA Times reports that Mr. Sterling told Clippers President Andy Roeser that Stiviano said that she would “get even” with Rochelle for filing the lawsuit. Apr. 26, 2014, Bettina Boxall, Sterling’s Wife Describes Alleged Mistress as Gold Digger in Lawsuit. I wonder if Stiviano has additional embarrassing Sterling recordings that she has not yet leaked. There is a controversy over whether the recordings were consensual. How are these leaked recordings related to the lawsuit?

Rochelle alleges that Donald Sterling provided the money for Stiviano to purchase the duplex, “with the understanding that the Property would be owned by [Donald and Rochelle Sterling] and title would vest in the name of [Rochelle] and D. Sterling.” Curiously, Donald is not a Plaintiff or Defendant to this lawsuit where the spouse sues paramour. Rochelle alleges that, “D. Sterling either gifted said Property to Stiviano, without the knowledge, consent or authorization of Plaintiff, or, in the alternative, Stiviano fraudulently and wrongfully caused title to the Property to vest in her name.”

Stiviano’s response focuses on the confusing and contradictory nature of Rochelle’s pleading. Her lawyer makes a few key arguments on demurrer:

- The transfers made from Donald to Stiviano were gifts.

- Rochelle and Donald are not in divorce proceedings.

- Rochelle does not allege that any of the transfers were thefts.

- Mr. Sterling is an, “on the top of his game infamous real estate mogul.”

- Rochelle knew of Donald’s reputation for “gold plated dalliances” in general and his relationship with Stiviano in particular.

Don Sterling’s health history is an issue. ESPN reports today that Mr. Sterling has prostrate cancer.

I try to avoid predicting the outcome of pending motions, especially those in California, where I do not practice law. Can a California Judge base a ruling on new facts introduced by a defendant on demurrer?

Rochelle alleges that she and Donald are the real owners of the duplex because either:

- Donald and his wife were supposed to be the grantees on the deed, and somehow the name got switched to Stiviano; or

- Donald secreted the funds to Stiviano out of the family estate without Rochelle’s knowledge.

These allegations seem contradictory. In the first case, there was an intention for the paramour to be the nominal purchaser for the benefit of the husband and wife. Did Rochelle condone Don’s relationship with Stiviano? The alternative alleges waste of marital assets, but outside a divorce proceeding. The “constructive trust” remedy sought by Rochelle is a flexible one. However, a spouse usually cannot invalidate transfers to a “other woman” absent theft, fraud, incapacity or other conduct that voids the intent of the philanderer.

This demurrer is set for hearing on July 8, 2014. Many things could happen before then. Don Sterling’s health is an issue. The media will shift their focus to other sports after the NBA Finals and Draft wrap up in late June. Will the NBA successfully force Sterling to sell the Clippers? His lawyers will research the admissibility of the Stiviano tapes thoroughly. Regardless as to how deep they go into the playoffs, the Clippers will have an eventful off-season.

March 20, 2014

“Is This a Film?” Video Within Video in the Justin Bieber Deposition

How is technology used in deposition and trials? Last week I attended Technology in Fairfax Courtrooms: Come Kick Our Tires!, a Continuing Legal Education seminar sponsored by the Fairfax Bar Association. This program interested me because real estate and construction cases are rich in photographs, plats, large drawings, sample construction materials and other visual evidence. Courts across Virginia are installing high-tech equipment for use in presenting pictures, video, audio and other media in trials. This seminar is a useful overview of the technological sea change in trial practice, including presenting audio and visual recordings of depositions at trial.

The credibility of a party’s testimony is at the heart of any trial. Sometimes parties and other witnesses will change their testimony. Lawyers use deposition records to test credibility on cross-examination. A video or audio recording can recreate the deposition vividly for the jury. Impeachment by video is not a feature of most trials because of significant time and expense associated with use of the technology.

At the courtroom technology seminar, someone mentioned pop music superstar Justin Bieber’s March 6th video deposition. This video leaked to the news media. The lawsuit alleges that Mr. Bieber’s entourage assaulted a photojournalist. I usually avoid following the news about celebrities’ depositions. I am familiar with the usual witness behavior. I’ve taken depositions of parties, experts and other witnesses. A celebrity may not be any more prepared for a deposition than an ordinary person. I watched excerpts of the Justin Bieber deposition on YouTube to see if it illustrated any new strategies.

In one excerpt, attorney Mark DiCowden shows a video of a crowd of people next to a limousine. Mr. Dicowden asked Bieber to look at the “film” on a screen behind the witness. The witness glances at the screen, turns back to DiCowden and evasively responds, “Is this a film?” DiCowden tried to focus Bieber on the video to establish a foundation for questions. As a viewer, I struggled watching the screen within a screen while following the examination. To capture Justin Bieber’s interaction with the video, the court reporter zoomed out, making both the video and Bieber smaller. If counsel tried to use this at trial, I imagine the jurors, sharing monitors, would struggle with this as well, with the added distraction of live court action. Justin Bieber’s evasive remarks and body language stand out here in what might otherwise be a disjointed use of technology. Since only excerpts are available, it is difficult to determine whether he went on to actually answer substantive questions about the video.

I wonder whether Plaintiff’s decision to incur the expense of this video deposition (and any related motions) will ultimately be useful for settlement or resolving the case in the courtroom. How will the deposition record look to the jury weighing the credibility of the witness? The Justin Bieber deposition provides some insight into use of video exhibits within a video recorded deposition. Getting an adverse witness to alternatively focus on questions and a video playing behind him is a challenge.

Even if your case does not involve celebrities, a practice run helps to prepare you for a video deposition. For example, the attorney taking the deposition could experiment with different layouts for the camera, people, screen and other visual exhibits to see how they look on replay. On the other side, the witness may learn something from viewing a video of himself answering practice deposition questions. Retain a lawyer with trial and deposition experience with evidence similar to your dispute.

featured image credit: Steven Wilke via photopin cc

March 6, 2014

How Should the Courts Determine Mortgage Fraud Restitution?

James Lytle and Martin Valadez ran a mortgage fraud operation. They submitted falsified applications and loan documents to mortgage lenders to finance the sale of real estate to straw purchasers. For procuring the purchasers and loans, Messrs. Lytle & Valadez obtained kickbacks from the sellers out of proceeds of the sales. See Mar. 15, 2009, “Amid Subprime Rush, Swindlers Snatch $4 Million.” Benjamin Robers was one of these “straw men.” Mr. Robers signed falsified mortgage loan documents for the purchase of two homes in Walworth County, Wisconsin. Lytle & Valadez paid Robers $500 per transaction.

Robers soon fell into default under the loans. A representative of the Mortgage Guarantee Insurance Corporation (“MGIC”) testified about its losses and those of Fannie Mae regarding one of the properties. American Portfolio held the lien on the other property. Robers pleaded guilty (as did Lytle & Valadez). In Robers’ sentencing, the Federal District Court based the offset value of the real estate on the prices obtained by the financial institutions in the post-foreclosure out-sales. The court ordered restitution of $166,000 to MGIC and $52,952 to American Portfolio.

What is restitution? Restitution is the restoration of the property to the victim. The term also encompasses substitute compensation when simply returning the defrauded property is not feasible. For mortgage fraud restitution, the outstanding balance on the loan is easy to calculate. More difficult is adjusting the loan balance for the foreclosure. In a criminal case, how much of an off-set is the defendant entitled for the home when the bank forecloses on it? On February 25, 2014, lawyers argued this question before the U.S. Supreme Court. Later this term, the Court will decide how to offset the foreclosure against the loan amount. Defendant Robers argues that the proper amount is the fair market value of the property on the date of the foreclosure. The government and the victim banks maintain that it should be the price that the bank actually sells the property to the next owner.

U.S. v. Benjamin Robers:

These questions came before the Court in Benjamin Robers’ an appeal from the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals and the Eastern District of Wisconsin. Robers argued that the Court wrongfully held him responsible for the decline in value of the homes between the dates of the foreclosure and the out-sales. He wants the Fair Market Value (“FMV”) of the property on the date of the foreclosure to serve as the proper off-set amount in the restitution award.

U.S. Mandatory Victims Restitution Act:

Under the Federal Mandatory Victims Restitution Act, when return of the property to the victim is impractical, the monetary award shall be reduced by, “the value (as of the date the property is returned) of any part of the property that is returned.” 18 U.S.C. section 3663A(b)(1). In mortgage fraud, the real estate is collateral. Usually the lender does not convey real estate to the defendant in the original sale. Rather, the defendant defrauded the lender out of the purchase money. At what point during the foreclosure process is the “property” “returned” to the victim? In oral argument, some of the Justices didn’t seem entirely convinced that the statutory return of the property language even applies. Justice Scalia observed that the banks were not actually defrauded out of money; the money went to the sellers. The banks thought they were getting a borrower who was more likely to repay over the course of the loan than he actually was.

Robers argues that since title passes to the lender at the foreclosure, that is the “date the property is returned” for purposes of calculating restitution. He argues that Fair Market Value of the property at the time of the foreclosure is the proper off-set amount. This is consistent with decisions of some federal appellate courts.

Foreclosures in Virginia:

Note that in Virginia, and in some other states also practicing non-judicial foreclosure, formal title does not pass at the foreclosure sale. That is when the auction occurs and the bank or other purchaser acquires a contractual right to the auctioned property. The bank or other purchaser disposes of the property after obtaining a deed from the foreclosure trustee.

Government Sides with Victimized Lenders:

In Robers, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the government and the financial institutions. The court pointed out that banks are in the money business, not the real estate investment business: “The two cannot be equated. Cash is liquid. Real estate is not.” Obtaining title to the real estate collateral at the foreclosure sale gives the bank something that it must take further steps to liquidate into cash that can be re-invested elsewhere. As the new owner of the property, the lender must cover management, taxes, utilities, insurance and other carrying costs. Any improvements to the property likely suffer depreciation during any unoccupied period.

The Seventh Circuit observed that the Courts which adopt a contrary position ignore, “the reality that real property is not liquid and, absent a huge price discount, cannot be sold immediately.” What is the relationship between the liquidity of real estate and a Fair Market Value appraisal? Federal law contains a definition of FMV:

‘The fair market value is the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or to sell and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.’ 26 C.F.R. Sect. 20.2031-1(b), cited in, U.S. v. Cartwright, 411 U.S. 546, 551 (1973).

The FMV of property, “. . . is not determined by a forced sale price.” 26 C.F.R. Sect. 20.2031-1(b) The price to liquidate property immediately would be a forced sale, and hence not represent FMV. An appraisal seeks to value real estate in cash terms. If the seller makes dramatic compromises on price to sell a property immediately, that same is not a good comparable sale in a FMV approach.

The Seventh Circuit decided that “Robers, not his victims, should bear the risks of market forces beyond his control.” A bank agrees to accept real estate as collateral for a loan on the premise that the loan application is not fraudulent. A bank is in the real estate investment business when it lends money under these circumstances. The risk that it may become saddled with a foreclosure property later is managed in its underwriting process. In the case of fraud, the “you asked for collateral, now you get collateral” defense is not appropriate. Participants in organized mortgage fraud will not be deterred if the restitution award includes no more than a deficiency judgment awarded in a civil case.

The Seventh Circuit equates “FMV at the foreclosure date” with “liquidation at the foreclosure date.” However, the FMV approach seeks to avoid the downward pressures on price associated with compelled liquidation. The Seventh Circuit does not discuss the FMV method in detail. They likely inferred that the financial institution lenders would incur carrying costs between the foreclosure and the future date when the market allows the property to be sold for near FMV. When a neighborhood suffers from a rash of foreclosures, appraisers may struggle finding useful comparable sales that aren’t short sales, deeds-in-lieu or foreclosures.

Daniel Colbert, blogger for the American Criminal Law Review, points out that the bank has greater control over how market changes affect the out-sale price than the defendant’s fraud. Nov. 26, 2013, Foreclosing Restitution: When Has a Lender’s Property Been Returned? If the victim still owns the foreclosed property at the time the court sentences restitution, does it get both the house and the full restitution award? Such a result seems unlikely with most institutional lenders. Justice Breyer suggested that in such a case, the court would require an appraisal if the lender doesn’t want to sell within 90 days after sentencing.

Interest of Mortgage Investors in U.S. v. Robers:

Unfortunately, mortgage fraud schemes like Lytle & Valadez’s occurred in Virginia as well. Financial institutions holding mortgages on distressed properties cannot wait upon the outcome of a mortgage fraud prosecution. They must timely represent the interests of their investors. When to foreclose and re-sell the property is a business decision. A Supreme Court decision in favor of the government would strengthen mortgages as an investment. Tougher restitution awards would deter perpetrators of mortgage fraud. Mortgage investors can mitigate their losses in mortgage fraud cases by documenting the expenses they incur as a result of the fraud. To the extent such a borrower has any ability to pay, he will heed a restitution sentence more than an ordinary deficiency judgment.

photo credit: Marxchivist via photopin cc

February 25, 2014

Reel Property: “The Attorney” and the Appearance of Justice

(This post is the second and final part in my blog series about the 2013 South Korean film “The Attorney.” Part I can be found HERE)

“The appearance of justice, I think, is more important than justice itself.”

Tom C. Clark explained in an interview why he resigned as a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. President Lyndon Johnson wanted to appoint Clark’s son, Ramsey, as U.S. Attorney General. The Constitution does not forbid a father from sitting on the Supreme Court while his son heads the Department of Justice. Tom Clark observed that although his son may not have anything to do with particular D.O.J. cases before the Supreme Court, the public would associate the outcome of the cases with the father-son relationship. The public develops its perceptions of the justice system more from news reports than personal experience. These perceptions help form the rule of law.

Tom C. Clark explained in an interview why he resigned as a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. President Lyndon Johnson wanted to appoint Clark’s son, Ramsey, as U.S. Attorney General. The Constitution does not forbid a father from sitting on the Supreme Court while his son heads the Department of Justice. Tom Clark observed that although his son may not have anything to do with particular D.O.J. cases before the Supreme Court, the public would associate the outcome of the cases with the father-son relationship. The public develops its perceptions of the justice system more from news reports than personal experience. These perceptions help form the rule of law.

The 2013 Korean film “The Attorney” reminded me of Justice Clark’s interview. This film is loosely based on the 1981 Busan Book Club Trial. In that case, attorney Roh Moo-hyun, the future President of S. Korea, defended a young man against terrorism charges supported by a written confession procured by torture of the defendants. A few days ago, I blogged about the first half of this film which focused on the attorney’s success building a real estate title registration practice. Today’s post explores the court drama at the climax of the movie.

The 2013 Korean film “The Attorney” reminded me of Justice Clark’s interview. This film is loosely based on the 1981 Busan Book Club Trial. In that case, attorney Roh Moo-hyun, the future President of S. Korea, defended a young man against terrorism charges supported by a written confession procured by torture of the defendants. A few days ago, I blogged about the first half of this film which focused on the attorney’s success building a real estate title registration practice. Today’s post explores the court drama at the climax of the movie.

One evening, lawyer Song Woo-seok (pseudonym for Mr. Roh, played by actor Song Kang-ho) entertains his high school classmate alumni at a restaurant managed by his old friend Choi Soon-ae (Kim Young-ae) and her teenage son, Park Jin-woo (Im Siwan). Song gets into a drunken argument with a journalist who defends the motives of student groups protesting the 1979 military coup. Song is a high school graduate who studied for the bar exam at night after working all day on construction sites. He struggles to understand the students’ idealism. Choi and Park are disappointed and angry about the property damage from the fight at their restaurant.

In a later scene, Park Jin-woo attends a book club meeting, where female students flirt with him about romantic content in a novel. The authorities raid the meeting and secretly take the students, including Park, into custody. Mrs. Choi searches for him all over Busan, even visiting the morgue. After many days, the authorities informed her of Park’s pending trial for crimes against national security. Choi begs Song to defend Park. Song’s loyalty to Choi and his journalist classmate overcome his reluctance to accept a perilous, politically-charged criminal case.

1. Personally Investigate the Real Property Before Trial

When attorney Song and Mrs. Choi visit Park in jail, his fatigued body is covered with bruises. Song interviews Park and his co-defendants about their arrest and detention. They describe the sounds of the street they heard from inside the interrogation location. Song locates and explores the mysterious building.

When I started litigating real estate cases, attorney Jim Autry explained to me the importance of a discreet first-hand view of the property at issue, including value comparables supporting an appraisal. Song’s risky investigation of the decrepit building where the police conducted the interrogations reflect his real estate and construction background. This on-site investigation allows him to interpret the documents and witness statements and try the case with confidence.

2. Verdict Preferences Develop Before Conclusion of the Evidence

This trial drama defies a conventional legal analysis because the verdict appears politically predestined. Attorneys going to the theater to see taut repartee under the rules of evidence will be disappointed.

The case is tried without a jury. Beforehand, the judge privately requests that defense counsel refrain from making a lot of objections and motions in front of the news media. The judge makes several early evidentiary rulings against Song and the defendants. Everyone anticipates a show trial imposing the political will of the military junta.

Song bravely transforms the case into more than a show of power. In interrogation, the defendants signed confessions that they read British historian E.W. Carr’s “What is History?” in their book club. The prosecution presents an expert who testifies that this book is revolutionary propaganda. On cross-examination, Song shows that this is required reading in the leading universities in South Korea. Song also tricks the prosecution into admitting that the expert’s offices are in the same building as the government’s intelligence service. This challenges the independence of the expert’s opinions.

3. False Confessions

Song calls Defendant Park to testify. Park explains that he signed the confession after many days of torture by the police. When Song presents photographs supporting the witness’s testimony, the prosecution argues that the wounds were self-inflicted.

Even without torture, false confessions are a common problem in criminal justice. Virginia Lawyers Weekly recently reported that 1/4 of all convicted defendants later exonerated by DNA made false confessions. Feb. 17, 2014, “Untruth or Consequences: Why False Confessions Happen and What To Do.” “Good cop/ bad cop” routines intimidating young, vulnerable defendants often lead to “confession” of details introduced by law enforcement during interrogation. Id.

4. Effect of Visceral Reactions of Courtroom Observers on the Trial Proceedings

Park’s testimony about the torture techniques brings the courtroom audience of family members and local media to tears. The authorities replace the families on the next day with a mob seeking a guilty verdict. Song’s examination of the police detective is a failure. The officer evades Song’s questions and lectures him about the threat of terrorism.

Just as the defense seems to peter out, Song and Park get a big break. Song meets the army medic used by the interrogators to keep Park alive during the interrogation. The medic courageously resolves to testify for the defendants about the nature and extent of the injuries. Song’s journalist classmate agrees to contact international media organizations in a desperate attempt to put pressure on the authorities about the medic’s testimony. The outcome hinges on the admission and credibility of the medic’s testimony.

5. Conclusion

Hollywood court dramas indulge their audiences with conclusive vindication. “The Attorney” reminded me that a system of justice is always a work in progress. Song evolves from construction laborer to moneymaking genius to litigator. Finally he becomes a civil rights leader motivated and tempered by his training and experience.

Song voice seemed frequently shrill during the trial. Perhaps a Korean speaker can comment on whether this was persuasive or detracting.

When a case turns into an uphill battle, attorneys sometimes rationalize that, “This could be worse.” The defense counsels’ role in the 1981 Burim trial must have been one of these worst-case scenarios. Average trial lawyers succeed for their clients when they can marshal favorable law and facts through in a legal system that works well. “The Attorney” presents an extreme case showing how courage, intelligence, loyalty and tenacity can earn the respect of colleagues, and in rare cases, a nation.

Perhaps Justice Clark would have respected Roh’s commitment. The villains in “The Attorney” see the criminal justice system as a blunt weapon and propaganda medium for use against critics of the military coup. This ultimately undermines the credibility of the legal system and weakens the rule of law. Attorney Song’s courtroom theatrics aren’t to make money or to cloak his personal insecurities. He takes risks out of deep loyalty to his client. Truth, not bullying, enhances the “appearance of justice.”

February 20, 2014

Reel Property: “The Attorney” (Korean, 2013)

Before Roh Moo-hyun became a human rights advocate and President of South Korea, he was a lawyer in private practice. Director Yang Woo-seok loosely based the 2013 Korean movie The Attorney (Byeon-ho-in) on Mr. Roh’s early career. After a blockbuster run in S. Korea, “The Attorney” now appears in American theaters. On Presidents Day, my wife and I watched this film, coincidentally featuring a foreign president. “The Attorney” has his weaknesses, but captures what it means to be an advisor, entrepreneur and advocate.

Song Kang-ho plays lawyer Song Woo-seok, a fictionalized, young Roh. Mark Jenkins observes that “The Attorney” begins as a comedy about a pioneer in land registration practice in Busan, Korea. Like a lawyer changing focus mid-trial, director Yang shifts gears in the middle of the film. Song accepts the defense of a young waiter who, after brutal torture, “confessed” to fomenting overthrow of the government. See Mark Jenkins, Feb. 6. 2014, Wash. Post, “‘The Attorney’ Movie Review: An Earnest and Instructive South Korean Box-Office Hit.”

Part One of this blog series focuses on Song’s success building a residential settlements practice. Part Two will focus on his trial preparation and advocacy for victims of human rights abuse.

Part One of this blog series focuses on Song’s success building a residential settlements practice. Part Two will focus on his trial preparation and advocacy for victims of human rights abuse.

1. Don’t Give Up – Re-calibrate and Move On:

Song pulls himself by his boot straps by maintaining a positive outlook. Before Song conducted legal settlements of homes, he literally built them. When I watched this film, I personally identified with the title character. After a day on the job, Song washes the construction site grime off his hands and starts to study. Your humble blogger worked as a laborer for a construction company during his college years. Song studied law in the evenings in neighborhood restaurants and unfinished buildings. I attended law school in an evening program while working a normal day job. A few years ago, I discovered culinary gems in Northern Virginia’s Korean restaurants. The restaurant scenes in the movie made me feel hungry!

After dinner at a restaurant managed by Choi Soon-ae, Song skips out on the bill. The dinner money goes to buy back his pawned law books. Song motivates himself by writing “Never Give Up” on the textblock of his books and into concrete facades at work sites. Song has little education or money to support his family or pay his debts. He uses “Never Give Up” to reinforce a positive outlook in the face of adversity. Writing or sharing a constructive affirmation can overcome self-doubt or the negativity of others.

2. Fearless Niching & Frequent Networking:

After passing the bar, Song receives a judgeship. Struggling to support his family, he resigns to found a real estate registration practice. This practice is similar to that performed by title companies and settlement agents in the U.S. Song capitalizes on a rule change authorizing attorneys to do work previously restricted to notaries public. Initially, his bar association colleagues scorn him for doing work they consider beneath them. At a bar meeting, he overhears them gossiping as they sit down to eat at his table. They complain that he is out meeting people and handing out business cards. Unperturbed, Song introduces himself and hands out his cards.

After Song finds financial success, his rivals follow him into this practice area, competing for the same customers. He reinvents himself again as a tax law advisor. Song’s vision and lack of pretension distinguish him from his colleagues. He fit his own background and talents with a high-volume consumer practice. Years after failing to pay the dinner bill, the new attorney returns to Mrs. Choi’s stew-house to repay his debt. She refuses, with motherly joy for a prodigal patron, insisting that he become a regular customer.

“The Attorney” features a foreign legal system and a different culture. I relied on the subtitles to follow along. In spite of cultural and linguistic barriers, the first half of the movie shows universal entrepreneurial strategies. Another WordPress blogger, Seongyong, has great photos from the film in his post.

In the first part of the film, the director develops Song’s character as worldly, warm & family-oriented. In the second half, Song puts his career, reputation and safety on the line to oppose anti-terrorism charges based on confessions procured by torture of the client. Stay tuned to the next blog post!

January 28, 2014

Divorce, Family Homes and Elliot in the Morning

On my Friday morning commute, I heard a guest on the radio show, Elliot in the Morning talking about his parents’ divorce, marriages and the legal fate of a family home. I rarely partake of EITM, but this time I stopped to listen (relevant portions of recording between minute marks 8:20-16:30 on YouTube).

Tommy Johnagin on Elliot in the Morning: Comedian Tommy Johnagin explained that when he was seven, his mother divorced his previous stepfather and married Johnagin’s current stepfather (none of this takes place in Virginia). The families lived in a small town. The current stepfather previously built a home with his own hands for himself and his ex-wife. When the current stepfather and his ex-wife divorced, the ex-wife got the house. Johnagin’s mother’s previous husband then married her current husband’s ex-wife (confused yet?). So Johnagin’s previous stepfather is now living in the home built with the sweat of the current stepfather’s brow. Johnagin commented to Elliot Segal: “I don’t even understand how this works.” In this portion of the interview, I was impressed with how Johnagin weaved some earthy insights into family life with funny personal narrative, such a recent chance encounter with the previous stepfather in the checkout line at the local Wal-mart.

What are the ways a family home can possibly reach this kind of outcome in divorce? Although the facts are different, the Supreme Court of Virginia published a January 10, 2014 opinion, Shebelskie vs. Brown, that discusses a possible route.

Betty & Larry Brown in the Virginia Court System: Betty and Larry Brown completed a divorce in Florida. One of their homes was Windemere, a landmark Tudor mansion in Richmond. (V.L.W. subscribers see July 22, 2013, “A Partition Suit Blows Up,” Virginia Lawyers Weekly) Sometimes, when an out-of-state divorce requires divvying up Virginia property, the parties will file an Equitable Distribution action in Virginia and the house matter will be referred to a court-appointed Commissioner. For reasons not discussed in the court opinion, this phase of the Brown divorce did not proceed this way. Instead, Larry filed a partition suit in Richmond, seeking an order that Windemere be sold.

In Virginia, when co-owners of real estate cannot agree on what to do with real estate, one party may file with the court a request for Partition and a Judicial Sale. See, Va. Code section 8.01-81, et sec. Partition traditionally involves dividing the parcel equitably into smaller parcels. When the land cannot conveniently be divided into smaller chunks because that would destroy the value of any improvements, the Court will usually grant a sale of the entire property. The monetary proceeds of the sale are then divided. Lawyers try to use partition suits as a last resort because they are a very expensive way to sell a house and more likely to lead to further title litigation. The deputy clerk called the Browns’ names week after week on the Richmond Circuit Court motions’ docket. The Court ordered a Judicial Sale. Finally, Betty obtained confirmation from the Court that she could go to closing on the house to buy-out Larry. The facts suggest that spousal support owed by Larry would end up helping to pay for the buy-out.

In the trial court, the parties litigated over attorneys’ fees and awards of sanctions issued by the judge against some of the attorneys. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Virginia reversed the sanctions award. (I invite my trial lawyer readers to take a look at the Court’s interpretation of the term, “motion” in the sanctions statute)

The Stepfather’s House, Revisited: How does the house that one man built for himself and his family end up in the possession of his ex-wife and his current wife’s ex-husband? Most likely, the home was part of the marital estate in the divorce and went to the ex-wife either in a settlement or by court order.

In a way, Tommy Johnagin’s current stepfather should be flattered that both his ex-wife and her subsequent husband desired the house he built. As a builder, he can construct another one.

In the interview, Johnagin commented that he felt content with the stepfather he got in the step-parent “lottery.” In the end, a good stepfather makes a bigger difference in someone’s life than title to a mansion or an appellate court victory.

photo credit: » Zitona « via photopin cc