July 20, 2017

Are Legal Remedies of Owners and HOAs Equitable?

Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy recently wrote in an opinion that, “Property rights are necessary to preserve freedom, for property ownership empowers persons to shape and to plan their own destiny in a world where governments are always eager to do so for them.” Murr v. Wisconsin, 198 L.Ed.2d 497, 509 (U.S. Jun. 23, 2017). This principle goes beyond the eminent domain issues in Murr v. Wisconsin. Many HOAs and condominiums boards or property managers are eager to make decisions for (or ignore their duties to) owners. In the old days, legal enforcement of restrictive covenants was troublesome and uncertain. In recent decades, state legislatures made new rules favoring restrictive covenants. Sometimes owners seek to do something with their property that violates an unambiguous, recorded covenant. I don’t see that scenario as the main problem. What I dislike more is community associations breaching their specific obligations to owners, as enshrined in governing documents or state law. Is the ability to enforce the covenants or law mutual? Are legal remedies of owners and HOAs equitable?

Why HOAs Wanted the Power to Fine:

Take an example. Imagine a property owner decides that it would be easier to simply dump their garbage in the backyard next to a HOA common area than take it to the landfill. Let’s assume that does not violate a local ordinance. Or substitute any other example where a property owner damages the property rights of others and the problem cannot be solved by a single award of damages. Before legislatures adopted certain statutes, the association would have to bring a lawsuit against the owner, asking the court to grant an injunction against the improper garbage dumping. This requires a demand letter and a lawsuit asking for the injunction. The association would have to serve the owner with the lawsuit. The owner would have an opportunity to respond to the lawsuit and the motion for the injunction. An injunction is a special court remedy that requires special circumstances not available in many cases. The party seeking it must show that they cannot be made whole only by an award of damages. The plaintiff must show that the injunction is necessary and would be effective to solve the problem. The legal standard for an injunction is higher than that for money damages, but it is not unachievably high. Courts grant injunctions all the time. However, the injunction requires the suit to be filed and responded to and the motion must be set for a hearing. Sometimes judges require the plaintiff to file a bond. Injunction cases are quite fact specific. The party filing the lawsuit must decide whether to wait for trial to ask for the injunction (which could be up to one year later) or to seek a “preliminary” or “temporary” injunction immediately. If the judge grants the injunction against the “private landfill,” the defendant may try to appeal to the state supreme court during these pretrial proceedings. These procedures exist because property right protections run both ways. Those seeking to enjoin the improper dumping have a right, if not a duty, to promote health and sanitation. Conversely, the owner would have a due process right to avoid having judges decide where she puts her trash on her own property. If the court grants the injunction, the judge does not personally supervise the cleanup of the dumping himself. If an order is disobeyed, the prevailing party may ask for per diem monetary sanctions pending compliance. That money judgment can attach as a lien or be used for garnishments. These common law rules have the effect of deterring the wrongful behavior. This also deters such lawsuits or motions absent exigent circumstances. Owners best interests are served by both neighbors properly maintaining their own property and not sweating the small stuff.

Giving Due Process of Court Proceedings vs. Sitting as both Prosecutor and Judge:

If association boards had to seek injunctions every time they thought an owner violated a community rule, then the HOAs would be much less likely to enforce the rules. The ease and certainty of enforcement greatly defines the value of the right. Boards and committees do not have the inherent right to sit as judges in their own cases and award themselves money if they determine that an owner violated something. That is a “judicial” power. Some interested people lobbied state capitals for HOAs to have power to issue fines for the violation of their own rules. To really give this some teeth, they also got state legislatures to give them the power to record liens and even foreclose on properties to enforce these fines.

Statutory Freeways Bypass the Country Roads of the Common Law:

Let’s pause for a second and pay attention to what these fine, lien & foreclosure statutes accomplish. The board can skip over this process of litigating up to a year or more over the alleged breach of the covenants or rules. Instead, the board can hold its own hearings and skip ahead to assessing per diem charges for the improper garbage dumping or whatever other alleged infraction. Instead of bearing the burden to plead, prove and persevere, they can fast track to the equivalent of the sanctions portion of an injunction case. Instead of enjoying her common law judicial protections, the owner must plead, file and prove her own lawsuit challenging the board’s use of these statutory remedies. Do you see how this shifts the burden? Of course, the HOA’s rule must meet the criteria of being valid and enforceable. In Virginia, the right to fine must be in the covenants. The statute must be strictly complied with. But the burden falls on the owner to show that the fast track has not been complied with.

Owners’ Options:

Statehouse lobbying and clever legal writing of new covenants has helped the boards and their retinue. Let’s take a moment to see what remedies the owner has. Imagine reversed roles. The board decided that they could save a lot of money if they dumped garbage from the pool house onto the common area next to an owner’s property. The board ignores the owners’ request to clean and maintain that part of the common area. Let’s assume that the governing documents require the board to maintain the common area and do not indemnify them against this kind of wrongful action. The owner can sue for money damages. If the case allows, the owner may pursue an injunction against the board to clean up the land and stop dumping trash. The owner must follow the detail-oriented procedures for seeking an injunction. The owner does not have a fast-track remedy to obtain a lien against any property or bank accounts held by the board.

Fine Statutes Should be Legislatively Repealed:

In my opinion, community association boards and owners should both be subject to the same requirements to enforce restrictive covenants. If state legislatures repealed their fine and foreclosure statutes, the boards would not be left without a remedy. They would not go bankrupt. Chaos would not emerge. They would simply have to get in line at the courthouse and play by the same rules as other property owners seeking to protect their rights under the covenants or common law.

“But Community Association Lawsuits are a Disaster:”

Many of my readers are skeptical of leaving the protection of property rights to the courts. They don’t like people who sue or get sued. They argue that whether you are defending or suing, the process is laborious and expensive. The outcome is not certain. I don’t agree that property owners should surrender their rights to associations or industry-influenced state officials. What if there was a controversy-deciding branch of government that the constitution separates from special-interest influence and the political winds of change? Wouldn’t that be worth supporting? I know that there are legal procedures that drive up the time and expense of the process without adding significant due process value. That does not mean that the courts should be divested of the power to conduct independent review and award remedies not available anywhere else.

Judicial Remedies Are Better Options Than Many Owners Think:

Fortunately, owners have many rights that their boards and managers are not informing them about. Many common law protections have not been overruled. In Virginia, restrictive covenants are disfavored. Any enforcement must have a firm footing in the governing documents, statutes and case law. The statutes adopted by the legislature limiting the common law protections are strictly (narrowly) interpreted by the courts. It is not necessary, and may be counterproductive to run to some elected or appointed bureaucratic official. Under our constitutional structure, the courts have the power to enforce property rights. Many owners cannot wait for the possibility that a future legislative session might repeal the fine statutes. If they are experiencing immediate problems (like improper dumping of garbage or whatever) they need help now. In rare cases law enforcement may be able to help. In most cases working with a qualified attorney to petition the local court for relief is the answer.

Photo Credit: duncan Commit no nuisance via photopin (license)

September 29, 2016

What is a Community Development Authority?

Every community is supposed to have a downtown as a destination for people to live, shop and play. The town center ideally keeps retail dollars and tax income from leaving the community. When these developments pop up, you hear discussions about whether “gentrification” helps or harms blue-collar people who live or work there. How does a developer decide where to place a new town center? In many places in Virginia, the local government offers to help finance the project with a special assessment district called a Community Development Authority (“CDA”). A CDA is where millions of dollars are financed through issuance of bonds paid off over many years by owners of real estate in the CDA district. The locality collects the assessments for the Community Development Authority. I take a personal interest in these CDAs because there is one in Fairfax County near me called the Mosaic District. Like many CDAs, Mosaic mixes residential homes and retail development.

“The Residences at the Lofts at SodoSopa”

A few days ago the Supreme Court of Virginia issued a new case opinion that provides an example of CDAs’ particular vulnerability to changes in the economy. Before I describe the case, I must first share something from pop culture with insight into recent trends in town center developments. A year ago, the television show South Park aired an episode called “The City Part of Town.” This episode lampooned these kinds of developments. I don’t often watch South Park because of some toilet bowl type humor they employ in other episodes. As a denizen of Northern Virginia, I love this particular episode. In this show, the “socially conscious” leaders of South Park wanted something that would, “Instantly validate us as a town that cares about stuff.” They created a new town center designed to lure Whole Foods Market to South Park. They named the district SodoSopa, shorthand for “South of Downtown South Park”. The episode focuses on a boy named Kenny whose family struggles financially but manage to keep their heads above water. SodoSopa develops around their “historic” home. Hipsters at trendy SodoSopa bars cause nighttime disturbances. The episode also features Mr. Kim and his asian restaurant, City Wok. The residents of South Park lose interest in City Wok when swank new restaurants open in SodoSopa. Mr. Kim takes desperate measures to try to keep City Wok from going out of business. City Wok hires a “child labor force.” Mr. Kim broadcasts commercials for his own restaurant district in an effort to compete with SodoSopa. In classic South Park fashion, the moronic adults engage in foolish behavior in vain attempts to achieve vainglorious objectives. According to Wikipedia.com, Whole Foods Market does open a store in fictional South Park, but not in SodoSopa. South Park’s gentrified district becomes abandoned because it failed to land the desired anchor tenant.

[embedyt] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=miXMWJyOdgw[/embedyt]

CDAs & “Overlapping Debt”

Unfortunately, the cartoon’s satire is not too far from reality. On September 22, 2016, the Supreme Court of Virginia published a new opinion in Cygnus Newport-Phase 1B, LLC v. City of Portsmouth. The case confronted the issue of “overlapping debt” in CDAs. Both bank loans and the CDA bonds finance these developments. If the local government records the CDA ordinance in land records after the bank files their deed of trust, which takes priority in foreclosure? Does the Community Development Authority have “super-priority” over “ordinary” liens? This case is of interest to anyone who conducts real estate settlements, foreclosures or wants to understand what it means to own real estate in a CDA.

New Port CDA

In 2004, Portsmouth Venture One, LLC (“PVO”) acquired a 176-acre developable tract of land in Portsmouth, Virginia. PVO used a Bank of America (“BOA”) mortgage to finance the purchase. In 2005, PVO successfully petitioned the city to set up New Port Community Development Authority. New Port CDA entered into a “Special Assessment Agreement” with PVO for finance of almost $17 million in infrastructure, including roads, utilities and lighting. PVO agreed that the City of Portsmouth could collect the special assessments to pay off the bonds financing the infrastructure improvements. The agreement provided that the special assessments, “does not exceed the peculiar benefit to the Assessed Property … resulting from the improvements,” and that PVO’s successors would be bound by the agreement. In 2006, the CDA’s resolution authorizing the bonds, the city’s ordinance establishing special assessments on the CDA properties and a declaration of notice of special assessment were recorded in the land records. The declaration provided that its provisions would “run with the land” and bind future owners of the subject property. The CDA handed approximately 75% of the bonds proceeds over to PVO to make the infrastructure improvements. PVO then began selling individual lots.

This is a particularly powerful type of financing. CDAs allow a developer to obtain millions of dollars up-front to pay for public infrastructure required in large projects. The Community Development Authority, as a local government entity, issues the bonds. The millions are supposed to be paid back by special assessments owed by the present (and successor) owners of the properties in the CDA. In addition to federal income tax, county property tax, state and local sales taxes, mortgage payments and community association dues, owners in a CDA must pay the special assessments collected by the city or county. Some of New Port CDA’s bonds would not be retired for 30 years.

Mortgage Foreclosure Crisis

2006 was a particularly unfortunate time to undertake an ambitious real estate project. A few years after the mortgage crisis began, PVO defaulted on its debt obligations, eventually losing its investment. In 2011, BOA sold its real estate loans to a company called Cygnus VA, LLC (“Cygnus”). Cygnus instructed the foreclosure trustee to conduct a sale. Cygnus itself purchased the property at the foreclosure sale, thus becoming the succcessor. Cygnus conveyed the property to other holding companies, but for the sake of brevity I will refer to all of them collectively as “Cygnus.”

Once Cygnus acquired these vast tracts, New Port CDA demanded the outstanding special assessments. Cygnus refused, insisting that the foreclosure stripped off the latter-recorded CDA lien that PVO allowed to encumber the property. Not wanting to pay the money or lose the property in a subsequent foreclosure, Cygnus filed a lawsuit. Cygnus argued that the foreclosure sale extinguished the special assessment lien. BOA was never party to the agreements with the CDA and city. Cygnus alleged that, physically speaking, there was very little to show for the millions provided to PVO by the CDA. The property purchased at the foreclosure was largely unimproved by infrastructure. How could New Port CDA claim a lien when there was little or no improvements to the foreclosed property that the new owner would be benefitting from? The circuit court found that this didn’t matter. Circuit Court Judge William S. Moore dismissed the lawsuit on the CDA’s motion. The Supreme Court of Virginia granted Cygnus’ petition for appeal.

Race-Notice Land Recordation & Super-Priority Liens

This New Port CDA case was a closely decided case by a 4 justice majority over 3 dissenters. Virginia appellate law blogger Steve Emmert describes this opinion as a “bar fight” among the members of the Supreme Court. I like his bar fight analogy because it makes me think of South Park’s fictional restaurant districts. The court majority decided that the bank foreclosure did not extinguish what was found to be a “super-priority” CDA lien. Virginia is a “race-notice” jurisdiction as far as real estate law is concerned. This means that between two parties who both recorded liens against real estate, the first one to record has priority. Cygnus appealed the case confidently – its title derived from BOA’s earlier-recorded deed of trust. However, the majority found that a special assessment lien is paramount over other encumbrances including a prior-recorded lien. They explained that a tax lien is superior in dignity because it is made by local governments for purposes of public improvements. The court found that it is not proper for a prior mortgage to defeat the process by which municipalities make property tax liens.

In response to this argument, the dissent points to the sections of the Virginia Code that specifically authorize the attachment of these CDA special assessment liens to real estate. The statutes mirror the “race-notice” rules that apply generally to land recordings. How can these special assessment liens enjoy “super-priority” status if the statute specifically provides otherwise? The Court ruled that because the city filed the ordinance before the foreclosure trustee’s sale, when Cygnus purchased the property, it was on notice of the special assessment liens.

The Shelter Doctrine:

Cygnus’ litigation strategy relied upon what is called the “shelter doctrine,” which has nothing to do with the habitability of any physical construction. Cygnus took title through BOA as a party without notice of any special assessment liens at the time the deed of trust was recorded. Under the “shelter doctrine,” if the mortgage lender’s interest in the real estate had priority over a later-recorded lien, then any party which takes title through the bank foreclosure enjoys the same lien priority. Under the shelter doctrine, the successor in interest of one who purchases the real property in good faith stands in the same position as the good faith purchaser even when the successor had notice of the lien through title examination. The shelter doctrine underlies the nonjudicial foreclosure system in Virginia. The purchaser at the trustee’s sale takes title from the trustee whose authority comes from the deed of trust made to benefit the lender.

The majority remarked that, “To permit such belated challenges would not only be contrary to the [Virginia] Code, it would completely unravel the entire legislative system of local improvements funded by special assessments.” The dissent argued that the majority rewrites the super-priority feature into the special assessment legislation which says otherwise.

“The Villas at Kenny’s House”

Remarkably, a CDA only requires the approval of the locality and 51% of the landowners’ interests in order to set it up. The 51% might be calculated by relative acreage or tax assessment appraised values. If non-consenting landowners oppose formation of the CDA, they have a very short deadline in which to petition the court to block it. In the South Park episode, Kenny’s family owned a small home included within the encompassing SodoSopa district. Of all the townspeople, only Kenny’s family attended a hearing where South Park heard public input on the creation of SodoSopa. If an owner has a larger developable tract as a neighbor, potential imposition of a CDA by the 51% and the county upon other landowners is a legitimate concern. The local government, not the owners, appoint the members of the CDA’s board.

What Might All of this Mean to Buyers and Owners?

I expect lenders to re-write their commercial loan underwriting and documentation processes in the wake of the Cygnus case. I can’t imagine Bank of America now agreeing to finance a project like this without forcing the developer to agree to obtain lender consent before petitioning for a Community Development Authority, or otherwise protecting their interests in writing. Why would a bank knowingly permit overlapping debt to obtain priority over their mortgage? Look for underwriting standards and loan documentation to tighten. Industry and governmental leaders want town center developments to continue and will want the players to get along.

The term “Community Development Authority” seems like a euphemism, like calling serfs “agricultural interns.” Someone who runs across the term might think that it is in charge of parks, libraries or children’s sport programs. CDAs are more accurately called a Higher Tax Area.

What does this new Cygnus case mean to owners of condos or townhouses in CDAs? An owner in one of these districts must pay the special assessments in order to avoid a sale to satisfy the liens. Like everything else in real estate, the owner must understand what the ordinances, abstracts, agreements and memoranda of liens mean. Owners should not assume that every CDA has the same governing provisions as one elsewhere. Likewise, anyone shopping for real estate should check whether it is located in a CDA and what those assessment obligations might be.

Independent Professionals Can Help with Understanding CDA Documents

Between HOAs, CDAs, mortgages and taxes, property owners have many potentially overlapping obligations and rules. HOAs & CDAs provide developers and local governments with means of shifting burdens to build and maintain common areas and infrastructure off of the county budget. While these strategies may work fine for creating these communities, they don’t always work well for owners, as shown by the South Park episode and the Supreme Court of Virginia opinion.

CDAs are a relatively new and potentially confusing phenomenon. Owners or prospective buyers should seek a qualified attorney to help them understand the obligations that come with the benefit of living in one of these districts. Investors should protect themselves against the potential risks that come with unanticipated responsibilities and town center developments that might fail.

For Further Reading:

Cygnus Newport v. City of Portsmouth, Supreme Court of Virginia, Sept. 22, 2016

Photo Credit:

m01229 The new Target store, coming to Merrifield via photopin (license)

July 15, 2016

Dealing with Memorandum for Mechanics Lien

A disgruntled contractor or supplier may attempt to collect a payment from owners by filing a Memorandum for Mechanics Lien against the real estate. Under Virginia law, claimants (contractors or material suppliers) can interfere with owners’ ability to sell or refinance property by filing a lien in land records without first filing a lawsuit and obtaining a judgment.

A March 2016 opinion by federal Judge Leonie Brinkema shows why purchasers at Virginia foreclosure sales must give care to mechanics liens. In April 2013 and October 2015 Jan-Michael Weinberg filed a Memorandum of Mechanics Lien against a Fairfax County property, then owned by Ann & James High. J.P. Morgan Chase Bank later foreclosed on the High property. In early 2016, Mr. Weinberg brought a lawsuit to enforce the mechanics lien against J.P. Morgan Chase and the property.

If a claimant pursues a Memorandum for Mechanics Lien correctly, the property may be sold to satisfy the secured debt. A Memorandum for Mechanics Lien is a two-page form that anyone can download online for general contractors or subcontractors. The filing fee is a few dollars. By contrast, removal of the lien may require significant time and attention by the owner. Overall, it is best for owners to work with their advisory team to avoid having contractors file mechanics liens in the first place. Sometimes, disputes cannot be easily avoided and owners must deal with recorded liens. A Memorandum for Mechanics Lien differs from a mortgage or a money judgment. Fortunately for the owner, Virginia courts apply strict requirements on contractors pursuing mechanic’s liens. Just because a contractor fills out all the blanks in the form that doesn’t meant it necessarily is valid. This blog post is a brief overview of key owner considerations. The Weinberg case provides a good example because the court found so many problems with that lien.

- Who? The land records system in Virginia index by party names. For this reason, the claimant must correctly list its own name and the name of the true owner of record. The owner’s team will need a title report and the construction contract. Whether the claimant is a general contractor, subcontractor or supplier will determine which form must be used. Mr. Weinberg’s Memorandum for Mechanics Lien claimed a lien of $195,000. Virginia law requires a contractor to have a “Class A” license for projects of $120,000 or more. Judge Brinkema found this Memorandum defective because Weinberg’s claim was not supported by a reference to a Class A license number. In some residential construction jobs, the Virginia Code requires appointment of a “Mechanic’s Lien Agent” to receive certain advance notices of performance of work from claimants that might later become the object of a mechanics lien. This creates an additional hurdle for the contractor, suppliers and subcontractors. In many construction projects, the builder works with the owner’s bank to obtain draws on construction loans. If mechanics lien disputes arise, owners can work with the bank to obtain documents.

- What? The Memorandum for Mechanics Lien must describe the dollar amount claimed and the type of materials or services furnished. The written agreement determines the scope of work, payment obligations and other terms. Generally speaking, only construction, removal, repair or improvement of a permanent structure will support a mechanics lien. Mr. Weinberg claimed that he conducted “grass, shrub, flower care,” “week killer,” “tree removal/cutting,” general property cleanup,” “infrastructure work,” “planting grass,” “site work,” “general household work” and “handy man jobs.” The Court found that this description of work was invalid. The work described was either landscaping or too vaguely connected to actual structures. Where the agreement was for work that could actually be the basis of a mechanics lien, the owner should consider how much of the work the contractor actually performed? Is the work free of defects? Does the Memorandum state the date the claim is due or the date from which interest is claimed?

- When? The contractor or supplier must meet strict timing deadlines for the mechanics lien. Generally speaking, the Memorandum for Mechanics Lien must be filed within 90 days from the last day of the month in which the claimant performed work. Judge Brinkema observed that Mr. Weinberg failed to indicate on the Memoranda the dates he allegedly performed the work. Also, no Memorandum may include sums for labor or materials furnished more than 150 days prior to the last day of work or delivery. Furthermore, the claimant must bring suit to enforce the lien no more than 6 months after recording the Memorandum or 60 days after the project was completed or otherwise terminated. Weinberg’s 2013 Memorandum was untimely because he did not sue to enforce it until 2016. Because Weinberg’s 2015 Memorandum was the same as the 2013 version, they both probably describe the same work on the property.

- Where? The Memorandum for Mechanics Lien must correctly describe the location of the real estate that it seeks to encumber. If it lists the wrong property, the lien may be invalid. Property description problems frequently arise in condominium construction cases because the same builder is doing work in the same building for multiple housing units. The Memorandum must be filed in the land records for the circuit court for the city or county in Virginia where the property is located.

- Why? There is usually a reason why a contractor decides to file a Memorandum for Mechanics Lien instead of pursuing some other means of payment collection. The Highs allegedly didn’t pay Weinberg for his landscaping and handyman services. The Highs’ weren’t able to pay their mortgage either. Weinberg filed for bankruptcy. In order to resolve a mechanics lien dispute with a contractor, an owner should consider how the dispute arose in the first place. Is someone acting out of desperation, confusion, or is the lien a predatory tactic? Could investigation need some other explanation?

- How? The owner must understand how the mechanics lien dispute with the contractor relates to the overall plan for the property. Mr. Weinberg tried to use mechanics liens to collect on debts. At the same time, he went through bankruptcy and the property went through foreclosure. Context cannot be ignored. Few owners can afford to remain completely passive in the face of a dispute with a contractor. The owner may have a construction loan or other debt financing to consider. An unfinished project is difficult to sell at a favorable price. Potential tenants won’t lease unfinished property.

On March 15, 2016, Judge Brinkema denied Mr. Weinberg’s motion to amend his lawsuit and dismissed the case. When a contractor or supplier files a Memorandum of Mechanics Lien against property, the owner must carefully consider whether to pay the contractor directly, deposit a bond into the court in order to release the lien and resolve the dispute with the contractor later, bring suit to invalidate the lien on legal grounds or simply wait 6 months to see if any suit is brought in a timely fashion to enforce the lien. Fortunately for owners, there are strict requirements on contractors for them to take advantage of mechanics lien procedures. A Virginia property owner should consult with qualified legal counsel immediately upon receipt of a Memorandum of Mechanics Lien to protect her legal rights.

Case Citation: Weinberg v. JP Morgan Chase & Co. (E.D. Va. Mar. 15, 2015)

Photo Credit: Views from a parking garage via photopin (license)

July 7, 2016

What is a Summons for Unlawful Detainer?

This blog post discusses the role of the Summons for Unlawful Detainer in Virginia foreclosures. “Unlawful Detainer” is a legal term for the grounds for eviction from real estate. The foreclosure trustee and new buyer go to a real estate closing a few days after the foreclosure sale. Upon settlement, the title company records the Trustee’s Deed of Foreclosure in the local land records. In most land transfers, the giver and recipient of the ownership of the real estate participate voluntarily. In a foreclosure, the borrower may contest the validity of the foreclosure transaction and the Trustee’s Deed. The Trustee’s Deed is necessary to the new buyer to pursue eviction proceedings against the occupants of the property. The Trustee’s Deed is the buyer’s legal basis for filing the Summons for Unlawful Detainer form. A copy of what this form looks like is available on the website for the Virginia court system.

Post-foreclosure evictions are not the only reason anyone files a Summons for Unlawful Detainer. Unlawful Detainer suits get into court in different situations. The most common is where a tenant fails to pay rent or defaults on the lease. However, it can be used for a variety of situations where an occupant entered onto the property with lawful authorization (such as a deed or lease) but has continued to occupy the premises after his right to do so ended. Every landlord knows that each month that the tenant holds over without paying is rental income that will likely never be collected. The General Assembly enacted legislation to streamline property owner’s rights to evict tenants and other persons unlawfully detaining possession of the real estate. This prevents an unfair result that might occur if a tenant could use lengthy court proceedings to live in the premises rent free when he may not have money to pay a judgment at the end. The buyer of the foreclosure property has made a financial commitment to own the property. Foreclosure investors want to evict the borrower, make any necessary repairs as soon as possible so that the property can be rented out or re-sold. So the summons for unlawful detainer form is a powerful, attractive tool for the new buyer in a foreclosure.

The investor or their attorney typically files the Summons for Unlawful Detainer in the local Virginia General District Court (“GDC”) after receiving the Trustee’s Deed. The GDC is the local court in Virginia most people are familiar with. This is where Virginians go for traffic ticket cases and suits for money under $25,000.00. The GDC has a “Small Claims Division” where parties litigate without lawyers. The Sheriff’s Office serves the Summons for Unlawful Detainer on the borrower and any other occupants. Upon receipt of the Summons for Unlawful Detainer, the borrower faces a “fight or flight” decision. Experienced lenders, trustees and purchasers know that the Trustee’s Deed of Foreclosure can be used as a weapon to try to crush the borrower’s opposition to the foreclosure. The Bank, trustee, and new buyer are can pursue these legal matters without the threat of having being evicted out of their base of operations. The borrower would not be in a foreclosure matter if there wasn’t a difficulty making payments. Once the Deed is in land records and the Summons is filed with the GDC, the borrower also has to mount a legal defense to keep possession of the home. A borrower is well advised to seek qualified legal counsel in his jurisdiction to help deal with these matters.

The Summons for Unlawful Detainer Summons must contain the name, address and point of contact for the new owner seeking to evict him. This will tell the borrower whether the property is now owned by the bank that requested the foreclosure or an unrelated investor. The Summons sets out when and where the borrower or his attorney must appear to contest the eviction proceeding. Every form states, “If you fail to appear and a default judgment is entered against you, a writ of possession may be issued immediately for possession of the premises.” A writ of possession is a document signed by the judge that authorizes the Sheriff’s Office to go out to the house and remove the people and belongings found there and turn it over to the new buyer and their locksmith.

What can a borrower do who has been wrongfully foreclosed upon and received a Summons for Unlawful Detainer? The earlier the borrower engages with legal counsel, the more there is that the attorney can do to help. On June 16, 2016, the Supreme Court of Virginia initiated legal reforms which dramatically shift the balance of power in these post-foreclosure evictions. If properly defended, the borrower may have an opportunity to get the dispute over the validity of the foreclosure decided before ordering eviction. This is good news. Prior legal precedent required many borrowers to defend against a Summons for Unlawful Detainer at the same time he pursued his own wrongful foreclosure claims against the bank and trustee. I discussed this new case in greater detail in my blog post, “The Day the Universe Changed” and in a radio show interview available in the “On the Commons” podcast library. While borrowers will continue to receive these “Summons for Unlawful Detainer” forms, they now have better options.

Unless the borrower does not intend to contest the eviction and foreclosure, borrowers receiving a Summons for Unlawful Retainer from the buyer of the foreclosure property should immediately seek qualified legal counsel in order to explore available options. The Virginia General Assembly is anticipated to enact new legislation in its next session to clarify the jurisdiction of the GDC and the appropriate court procedures when a borrower contests the validity of a foreclosure related to the eviction proceeding. With assistance, borrowers may be able to take advantage of these legal reforms.

photo credit: GEDC1290 s via photopin (license)

July 6, 2016

What is a Notice of Trustees Sale?

Bankers and lawyers send many notices, letters and statements to borrowers struggling with their mortgage. The purpose of such paperwork is to collect on the mortgage debt. In Virginia, the Notice of Trustees Sale is very significant. In Virginia, the bank does not have to go to court first in order to obtain a foreclosure sale. The law permits the property to be sold by a trustee in a transaction outside of the direct supervision of a judge. The Foreclosure Trustee cannot conduct a valid foreclosure in Virginia without sending a proper Notice of Trustees Sale. The Trustees Sale is a public auction of the property to the highest bidder, usually on the courthouse steps. In order to protect her rights against abusive foreclosure tactics (examples discussed elsewhere on this blog), the borrower must understand the role this Notice of Trustees Sale plays. Borrowers exploring the possibility of contesting the foreclosure should retain qualified legal counsel when they receive the Notice of Trustees Sale.

When borrowers go to closing on the purchase or refinance of Virginia property, they review and sign a loan document called a Deed of Trust. Virginia judges treat Deeds of Trust as the “contract” between the borrower, lender and trustee regarding any foreclosure. The Deed of Trust imposes specific requirements on the lender if they want to foreclose. The bank is required to follow these requirements regardless as to whether the borrower is in default on the loan or not. Deeds of Trust describe what the Notice of Trustees Sale must include, who it must be sent to, requirements for it to be published in the newspaper, etc. The Virginia Code also has specific requirements about the Notice of Trustees Sale and its newspaper publication. The Notice of Trustees sale is more than a tool to intimidate the borrower or provide a courtesy to someone about to lose their home. The Notice is an essential building block. Absent this, the foreclosure is not valid.

Upon receiving the Notice of Trustees Sale, Borrowers must take seriously the trustee’s stated intention to foreclose on the property at the date written. For various reasons, lenders and trustees will cancel or postpone trustee’s sale, but they won’t do this simply upon request by the borrower. If the lender or trustee indicates that the sale has been temporarily cancelled or postponed, the borrower may request for written confirmation.

The Notice of Trustee’s Sale is an invitation to make an offer to enter into a contract for the property with the purchaser at the sale. The two main documents in a Trustees Sale are the Memorandum of Sale and the Trustee’s Deed of Foreclosure. The Memorandum of Sale is a written contract between the trustee and the new buyer. Some Deeds of Trust require that the trustee and the buyer make their contract on the terms set forth on the Notice of Trustee’s Sale. Sometimes trustees put additional terms into these Memoranda which create other contractual rights which may be of interest to the borrower. The Trustee’s Deed is the document conveying ownership of the property to the new buyer. A borrower investigating the validity of the foreclosure should carefully review the Deed of Trust, Notice of Trustees sale, Memorandum of Sale and Trustee’s Deed to determine whether any of the latter documents breach of the Deed of Trust. If the trustee refuses to provide a copy of the Memorandum of Sale, the borrower should seek the assistance of qualified legal counsel. Both the borrower and any potential purchasers are generally entitled to rely upon the terms of the Notice of Trustees Sale in making informed decisions about it. If the lender and trustee sell the property on terms and methods contrary to the Notice of Trustees Sale, then the Trustee’s Deed may be invalid. The validity of the Foreclosure Trustee’s Deed is an issue of great interest to any victim of wrongful foreclosure.

Many homeowners fighting foreclosure observe many contradictions between their loan documents, mailings received from the bankers and their lawyers, and the things they are told on the phone by the bankers and the banker’s lawyers. The banks have experienced foreclosure attorneys whom they may have instructed to aggressively pursue the foreclosure and eviction. The Notice of Trustees Sale is one of the essential “gears” in the “foreclosure factory” borrowers contend with. Receipt of this document may be the best time to contact qualified legal counsel to discuss your rights and options available for keeping your home.

Relevant Statute: Va. Code § 55-59.1. Notices required before sale by trustee to owners, lienors, etc.; if note lost.

July 1, 2016

False Promises of Loan Modifications in Fraudulent Foreclosure Cases

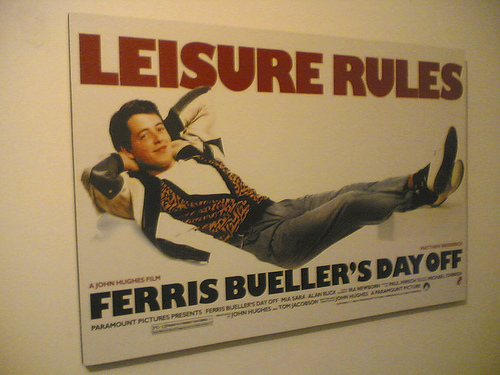

In the classic comedy, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Ferris’s mother meets with the assistant principal to discuss his absenteeism. She had no idea he took 9 sick days. The school official bluntly explains: “That’s probably because he wasn’t sick. He was skipping school. Wake up and smell the coffee, Mrs. Bueller. It’s a fool’s paradise. He is just leading you down the primrose path.” Mothers of truant teenage sons aren’t the only ones succumbing to the temptation of wanting to believe that everything is fine when it isn’t. Owners busy with their jobs and families would like for their home to be worry-free. Unfortunately, the Ferris Bueller’s of the world sometimes grow up to service mortgages, manage HOA’s and handle customer service for home builders. The real estate and construction industry has some predators who lead consumers on the “primrose path.” We are not talking here about mere “sales talk” and “puffery” (for example, someone merely says that they will “treat you like family”). Promissory Fraud is when someone makes promises with no intent to follow-through but with every desire for the listener to rely upon it. In the past few years, borrowers have sued mortgage servicers for false promises of loan modifications in fraudulent foreclosure cases. Loan servicers stand in the shoes of the original mortgage lender as far as the borrower is concerned. Servicers send out the loan account statements, collect the payments and make disbursements. These cases allege that the servicers used “primrose path” tactics to conduct foreclosure fraud.

Leading along the primrose path is a powerful ploy because of the psychological roller-coaster the consumer experiences. Financial struggles, default notices and foreclosure letters causes stress and troubles that impact owners’ resources, time and relationships. Promises of time extensions, foreclosure avoidance and loan modifications are spellbinding. They invite the consumer to the much-missed happy place of living their life without threat of catastrophic financial loss. If the servicer says just the right thing, the borrower will very naturally want to let down their guard and forego more arduous tasks of forging a legal and financial solution to the problems. The false sense of security is intoxicating. When the borrower later experiences foreclosure instead of the promised modification, they are left trying to pick up the pieces.

Randolph Morrison vs. Wells Fargo Bank:

Mortgage servicers often get away with this because borrowers don’t always pay close attention to what they are actually being told. When borrower listen and take notes, they protect themselves. In 2014, a federal judge in Norfolk considered a claim for fraud based on telephone misrepresentations that Wells Fargo Bank allegedly made in the foreclosure context. When Virginia Breach homeowner Veola Morrison died in 2009. Her family received a notice that the property would be foreclosed on January 19, 2011. Veola’s son Randolph offered to assume the mortgage and requested an interest rate reduction. On January 12, 2011, a Wells Fargo employee told Randolph that he was approved for a loan modification and that the January 19, 2011 foreclosure would not take place. Wells Fargo sent Randolph a letter dated January 14, 2011 offering him a special forbearance agreement, requiring him to make his first payment on February 1, 2011. A “forbearance” is when the lender agrees to hold off on foreclosure and collection activities for a period of time in anticipation that the borrower will resolve short-term cash flow difficulties. They said that the foreclosure would be suspended so long as Randolph kept to the terms of the agreement. In spite of these representations, Wells Fargo Bank’s substitute trustee conducted the foreclosure sale anyway on January 19, 2011. In his suit, Randolph alleged that he reasonably relied upon a telephone statement by Wells Fargo that the January 19, 2011 foreclosure would not occur. He relied upon the subsequent letter saying when he had to make his next monthly payment. Relying on these representations, Randolph did not take other actions to prevent foreclosure such as hiring an attorney. After he discovered what happened, Randolph sued Wells Fargo. The Court denied Wells Fargo’s initial motion to dismiss the case and allowed Randolph’s claim for promissory fraud to proceed in Court. The case settled before trial.

Mortgage servicers often get away with this because borrowers don’t always pay close attention to what they are actually being told. When borrower listen and take notes, they protect themselves. In 2014, a federal judge in Norfolk considered a claim for fraud based on telephone misrepresentations that Wells Fargo Bank allegedly made in the foreclosure context. When Virginia Breach homeowner Veola Morrison died in 2009. Her family received a notice that the property would be foreclosed on January 19, 2011. Veola’s son Randolph offered to assume the mortgage and requested an interest rate reduction. On January 12, 2011, a Wells Fargo employee told Randolph that he was approved for a loan modification and that the January 19, 2011 foreclosure would not take place. Wells Fargo sent Randolph a letter dated January 14, 2011 offering him a special forbearance agreement, requiring him to make his first payment on February 1, 2011. A “forbearance” is when the lender agrees to hold off on foreclosure and collection activities for a period of time in anticipation that the borrower will resolve short-term cash flow difficulties. They said that the foreclosure would be suspended so long as Randolph kept to the terms of the agreement. In spite of these representations, Wells Fargo Bank’s substitute trustee conducted the foreclosure sale anyway on January 19, 2011. In his suit, Randolph alleged that he reasonably relied upon a telephone statement by Wells Fargo that the January 19, 2011 foreclosure would not occur. He relied upon the subsequent letter saying when he had to make his next monthly payment. Relying on these representations, Randolph did not take other actions to prevent foreclosure such as hiring an attorney. After he discovered what happened, Randolph sued Wells Fargo. The Court denied Wells Fargo’s initial motion to dismiss the case and allowed Randolph’s claim for promissory fraud to proceed in Court. The case settled before trial.

Alan & Jackie Cook vs. CitiFinancial, Inc.:

Just because a false reassurance is not in writing doesn’t mean that the borrower can’t sue for fraud. Virginia Federal Judge Glen Conrad considered this question in 2014. Jackie & Alan Cook owned a property in Lovington, Virginia. In September 2011, Mr. Cook explained to his lender CitiFinancial, Inc. that he was current on his loan but struggling to make payments. The branch manager suggested that he pursue a loan modification through the Home Affordable Modification Program (“HAMP”). The manager told Mr. Cook that if he stopped paying, the lender would “have to modify the loan” and it would probably be able to cut the interest rate and principal owed. Mr. Cook became leery and asked questions. The manager reiterated that he should just stop making payments and ignore the bank’s letters until he received a notice with a date for the foreclosure sale. The customer services rep told Mr. Cook that once he got the foreclosure notice he could call the number on it and get started. Per the manager’s instructions, Mr. Cook stopped making payments and ignored the servicer’s default letters.

On June 17, 2013, Cook received a notice that on July 17, 2013, foreclosure trustee Atlantic Law Group would sell his Nelson County property in foreclosure. Remembering what CitiFinancial originally said, Cook tried to call the loan servicer 20 times, receiving no answer or he was hung up on. Finally, on July 11, 2013, Mr. Cook got ahold of CitiFinancial who told him what information they needed for a loan modification. When Mr. Cook talked to another employee of the servicer, he was told that his case would remain on “pending/hold status” for 30 days in order for him to obtain the necessary documents, and that the scheduled foreclosure would be postponed during that time. On July 17, 2013, the noticed day of foreclosure, one employee of the servicer told him on the telephone the “great news” that he was awarded a loan modification. Later that day, he talked to another employee of the servicer who told him that the foreclosure would indeed proceed as originally scheduled, because he failed to provide them with necessary documents. When Mr. Cook asked her about the 30-day hold period that he was previously given, she replied that “she had never heard of such a thing” and that there was nothing to be done to stop the foreclosure sale. Notice how the servicer used a new misrepresentation about the 30-day period to keep Mr. Cook on the “primrose path” even after he struggled to communicate with him after defaulting per their instruction. Mr. Cook rushed to an attorney’s office but by the time the trustee received the attorney’s letter the sale had already occurred. Use of the primrose path strategy is particularly damaging because the new buyer can use the foreclosure trustee’s deed to initiate eviction proceedings. Citi bought this property at the trustee’s sale and brought eviction proceedings against Mr. Cook. Cook filed suit, basing fraud claims on the servicer’s false promises. CitiFinancial initially moved for the court to dismiss the lawsuit, arguing that Cook could not have reasonably relied upon the false oral representations because the promissory note and deed of trust provided unambiguous terms for foreclosure in the event of default. Citi seemed to be saying that only things that are in writing are official in the mortgage context. Judge Glen Conrad rejected this argument because the question of whether Cook was justified to rely upon Citi’s oral statements was an evaluation of the credibility of witnesses at trial.

Jackie & Alan Cook’s case settled before trial. An agreed order reversed the foreclosure sale. While a servicer misrepresentation doesn’t have to be in writing to constitute fraud, the dispute may come down to a “he-said she-said” at trial. Few borrowers will take careful notes at the time these discussions take place. While defendants may be required to make document disclosures, homeowners can’t count on getting copies of servicer notes and internal messages during the litigation. Search warrants are not available in civil cases.

The experiences of the Morrisons and Cooks are common amongst different lenders all across the country. It’s best for homeowners struggling with their mortgages avoid the “primrose path” promises made by some servicers, foreclosure trustees and foreclosure rescue scams. If it sounds too good to be true, then it deserves thorough review and consideration. However, there are many situations where relying upon the representations of a lender or trustee is the only reasonable option. Once the foreclosure trustee’s deed is recorded, the borrower may face eviction proceedings. If a trustee or servicer breaches the mortgage documents or makes misrepresentations in conducting a foreclosure, the borrower should contact qualified legal counsel immediately.

Case Citations:

Morrison v. Wells Fargo Bank, 30 F. Supp. 3d 449 (E.D. Va. 2014)

Cook v. CitiFinancial, Inc., 2014 U.S. Dist. Lexis 67816 (W.D. Va. May 16, 2014)

Photo Credit:

June 21, 2016

The Day the Universe Changed

My parents are retired schoolteachers. Growing up, we watched our share of public television. I remember watching a British documentary by James Burke called, “The Day the Universe Changed.” This program focused on the history of science in western civilization. Scientific developments affect public perceptions of man’s place in the world. Each episode dramatically built up to a momentous change in scientific perception. For example, when scientists determined that the earth circles the sun (and not the opposite), it felt as though the “universe changed.” The title of the final episode was, “Worlds Without End: Changing Knowledge, Changing Reality.” Provocative stuff for 1985. I went on to study the history of science for four years in liberal arts college.

Property: Ownership & Possession:

In the law there is a difference between the reality of how people think and act in real life, on the one hand, and the reality of courthouse activities on the other. For example, people frequently lie when under the stress of questioning. Courts developed a comprehensive set of evidence rules to determine what documents and testimony are acceptable. The rules of evidence are not a formalization of the way people ordinarily evaluate truth-claims. As another example, outside of Court, non-lawyers understand the difference between the right of ownership and the right to possess or occupy any property. The right of ownership is superior to, and often includes the right to possess. These rights are distinct but unseverably connected. Attorneys and nonlawyers understand the difference between being an owner, a tenant, or an invited guest. By contrast, since before the Civil War, Courts in Virginia enforced the conceptual separation between the right to claim ownership and the right to evict an occupant and gain exclusive possession. The courts did this by not allowing an occupant to raise a competing claim of ownership as a defense in an eviction suit. In many cases, attorneys would have to “lawsplain” why a borrower could not effectively assert the invalidity of the foreclosure in the eviction case brought by the new buyer. Practically speaking, the borrower had to defend the eviction case while also filing another, separate lawsuit of her own to raise her claims to rightful title to protect her property rights. The rules required a financially struggling borrower to litigate overlapping issues in two separate cases at the same time against overlapping parties. If you are reading about this and think that it makes no sense, you are right, it doesn’t. But this was the way that the Virginia eviction world worked for a very long time.

Instant Legal Reform:

And then June 16, 2016 was the day the entrenched worldview of foreclosure contests and evictions in Virginia changed forever, or at least until the General Assembly holds its next session. The Supreme Court of Virginia published a new opinion overturning 150-200 years of precedent in this area. This opinion is important to anyone who lives or works in any real estate with a mortgage on it. Virginia appellate law blogger Steve Emmert observed that this decision represents a “nuclear explosion” and that “. . . dirt lawyers are going to erupt when they read . . .” This case is a game-changer that unsettles much of real estate litigation in Virginia.

My Professional Interest:

Since the foreclosure crisis exploded in 2008, I have litigated foreclosure cases in Virginia on behalf of borrowers, lenders and purchasers. Before June 16, 2016, few expected the rules of the road to change dramatically. The Supreme Court of Virginia has hundreds of years of precedent underlying the existing state of affairs. The banking industry maintains an effective lobbying presence with the General Assembly. Victims of foreclosure abuses play the game of survival; few become activists. Yet, common-sense would dictate that having two separate lawsuits (the eviction case and ownership dispute) proceeding through the court system at the same time wastes resources for everyone. This impacts borrowers the most because they are in the least favorable position to pursue multiple lawsuits at the same time.

Parrish Foreclosure Case:

Teresa and Brian Parrish took out a $206,100 deed of trust (mortgage) on a parcel of real estate in Hanover County, Virginia. This deed of trust’s provisions incorporated certain federal regulations into its terms. These regulations prohibited foreclosure if the borrower submitted a complete loss mitigation application (a.k.a., loan modification application packet) more than 37 days before the trustee’s sale. Federal National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”) had an interest in the home loan. The Parrishes timely submitted their application packet. Regardless, in May 2014, ALG Trustee, LLC sold the Parris property to Fannie Mae at the foreclosure sale. Fannie Mae then filed an unlawful detainer (eviction) lawsuit against the Parrishes in the General District Court (“GDC”). The GDC is the level of the court system that most Virginians are familiar with. People go to the GDC for traffic tickets, collection cases $25,000.00 or less, evictions and “small claims” cases. In the GDC, the Parrishes did not formally seek to invalidate the foreclosure sale. Instead, they argued that they were entitled to continue to possess the property because ALG conducted the foreclosure sale while the loan modification application was pending. The GDC judge took a look at the Trustee’s Deed that ALG made to Fannie Mae and ordered the sheriff to evict the Parrish family. The Parrishes appealed the case to the Circuit Court. The Circuit Court granted a motion affirming the lower decision in Fannie Mae’s favor. The Parrishes sought review of the case by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court of Virginia’s June 16th opinion is a mini-treatise for the new landscape of foreclosure legal challenges.

Questions of Ownership and Occupancy Are Inextricably Intertwined:

The Justices directly addressed the question of the GDC’s jurisdiction. Unlike the Circuit Court, the GDC does not have the statutory legal authority to decide competing claims to title to real estate. That said, in each post-foreclosure unlawful detainer case the GDC must base its decision on whether the presentation of the Trustee’s Deed of Foreclosure is sufficient evidence of title to grant the eviction. Under longstanding legal precedent, the Parrishes’ contention about their loan modification application would not be heard in the unlawful detainer case because the borrowers can’t invalidate the foreclosure deed in the GDC. But on June 16, 2016 that all changed. The majority found that the validity of the foreclosure purchaser’s claimed right to possess the premises cannot be severed from the validity of that buyer’s claimed title because that title is the only thing from which any right to occupy flows. “The question of which of the two parties is entitled to possession is inextricably intertwined with the validity of the foreclosure purchaser’s title.”

From this insight, one must call to question the practical requirement for the borrower to bring his own separate lawsuit against the buyer, trustee and lender to reverse the foreclosure, confirm the right to possess and other relief. Why not have a procedure where all of the related claims can be combined?

What Are Lawyers to Do Now?

Okay, now the “universe has changed.” How do borrowers raise this issue in defense of post-foreclosure evictions? Is there anything that the foreclosure buyer can do about this? The Supreme Court recognizes many reasons why a borrower might have a legitimate claim that the foreclosure sale was legally defective, including but not limited to:

- Fraud (by the lender and/or foreclosure trustee)

- Collusion (between the trustee and the purchaser)

- Gross Inadequacy of Sale Price (so low as to shock the conscience of the judge)

- Breach of the Deed of Trust (for example the regulations about the loan modification application)

The Supreme Court’s new opinion states that the homeowner could allege facts to put the validity of the foreclosure deed in doubt. By the court’s new standard, if the borrower sufficiently alleged such a claim, the GDC becomes “divested” of jurisdiction. When the judge determines that he has no jurisdiction because there is a bona-fide title dispute, he must dismiss the entire case. From there, the new buyer would have to re-file the case in the Circuit Court where the parties would then litigate everything.

I expect that the General Assembly will enact new legislation in its next session that will clarify the jurisdiction of the GDC and the procedures for post-foreclosure unlawful detainers. At least until then, purchasers and lenders will not have the same ability to use the unlawful detainer suit as a weapon in their struggles with borrowers in foreclosure contests. Homeowners’ abilities to fight foreclosures will be streamlined. Justice McClanahan wrote a dissent where she explained the meaning of this in remarking that the majority of justices,

practically eliminated the availability of the summary [i.e. expedited] proceeding of unlawful detainer to purchasers of property at foreclosure sales. The majority’s new procedure for obtaining possession operates to deprive record owners of possession until disputes over “title” are adjudicated after the record owner has sought the “appropriate” remedy in circuit court.

The Supreme Court of Virginia reversed the decision of the Circuit Court and dismissed the unlawful detainer proceeding brought against the Parrishes.

Conclusion:

I welcome the Court’s recognition that the rights of title and possession are “inextricably intertwined”. In post-foreclosure disputes between the borrower, purchaser, lender and trustee, bona fide ownership claims should certainly be decided in court before the sheriff kicks anyone out of their house. Eviction procedures should not be used as a weapon to railroad homeowners out of their houses. It makes no sense for there to be more than one legal case about the same thing. Hopefully the General Assembly will adopt new legislation accepting these revelatory developments while clarifying and streamlining court jurisdiction and procedures so that the parties need not litigate any more than is necessary to properly decide who has the right to own and possess the foreclosure property. The universe has changed, and we are closer to a future where the court procedures do not unfairly burden one side over the other and it is easier for each case to be decided on its merits and not who runs out of money first.

UPDATE: I was interviewed by Shu Bartholomew on her radio show/podcast, “On the Commons” about this Parrish v. Fannie Mae case. The podcast is now available.

Case Citation: Parrish v. Federal National Mortgage Association (Supr. Ct. Va. Jun. 16, 2016)

Photo Credit: 2012/11/12 OOFDG Defending Jodie’s Home via photopin (license)(does not depict the property discussed in this article)

April 22, 2016

Milwaukee is in a Tussle with Banks over Zombie Foreclosures

When an owner defaults on her mortgage, sooner or later she must determine if she is willing and able to keep the property. In my last blog post, I considered a situation where an owner might find their HOA attempting to force the bank to expedite a delayed foreclosure. In my opinion, neighbors and HOAs should not interfere with an owner’s bona fide efforts to save their home and avoid foreclosure. However, the owner does not always desire to keep the property. Some owners want their property to be sold to cut off their obligations to maintain the property, pay taxes, and HOA assessments. What rights does an owner have to force a lender to expedite the foreclosure? What interest does the city or county have to hurry up foreclosure? In Wisconsin, the City of Milwaukee is in a tussle with banks over zombie foreclosures. On February 17, 2015, the Supreme Court of Wisconsin decided that where a bank files suit to foreclose and when the court determines that the property is abandoned, the sale must occur within a reasonable period of time. The banking industry would prefer to postpone completing foreclosure if expediting things would force them to pay fees to acquire property they don’t actually want. Wisconsin Assembly Bill 720 currently sits on Governor Scott Walker’s desk, which if signed would give banks greater flexibility in delaying or abandoning foreclosures. Why are the banks seeking to amend the foreclosure statutes in response to this judicial opinion?

As Fairfax attorney James Autry says, an abandoned home is a liability, not an asset. Unoccupied residences can be victimized by vandals, squatters, arsonists, and infested by vermin. In the winter the pipes can burst, causing thousands of dollars of damage. Local governments struggle to collect taxes on the property and HOAs are not able to collect assessments and fines for the home. The abandoned homes may become an eyesore and affect neighboring property values. The hallmark of truly “zombie” properties is that no one wants them because their costs and liabilities exceed their value.

The subprime mortgage crisis transformed many properties in Milwaukee into “zombie foreclosures”. On April 11, 2016, Mayor Tom Barrett published an op/ed stating that there are currently 341 properties in Milwaukee that are simultaneously vacant and in foreclosure proceedings. He fears that if the governor signs the new legislation, the city would be forced to conduct tax sales and take ownership of the properties to remove the blight. In these situations, neither the owner, the bank, nor the city are interested in maintaining the home or expediting a sale. These homes are so distressed that the city and the banks are fighting over who doesn’t have to assume responsibility for them.

The subprime mortgage crisis transformed many properties in Milwaukee into “zombie foreclosures”. On April 11, 2016, Mayor Tom Barrett published an op/ed stating that there are currently 341 properties in Milwaukee that are simultaneously vacant and in foreclosure proceedings. He fears that if the governor signs the new legislation, the city would be forced to conduct tax sales and take ownership of the properties to remove the blight. In these situations, neither the owner, the bank, nor the city are interested in maintaining the home or expediting a sale. These homes are so distressed that the city and the banks are fighting over who doesn’t have to assume responsibility for them.

AB 720 came as a response to the very pro-municipality court decision BNY Mellon v. Carson. This case provides a good example of a “zombie” foreclosure. Shirley Carson put up her home on Concordia Avenue in Milwaukee as collateral to borrow $52,000 from Countrywide Home Loans. Wisconsin is a judicial foreclosure state where the bank has to file a lawsuit as a prerequisite to obtaining a foreclosure sale of the property. However, merely filing the foreclosure lawsuit does not transfer title to the distressed property. In Wisconsin, the court needs to order a sale. When Ms. Carson defaulted on her mortgage, the Bank of New York, as trustee for Countrywide filed a lawsuit for foreclosure.

The bank attempted to serve the lawsuit on Carson at her residence. The process server could not find her. He observed that the garage was boarded up, snow was un-shoveled and the house emptied of furniture. The property was burglarized. Vandals started a fire in the garage. The City of Milwaukee imposed fines of $1,800 against Carson because trash accumulated and no one cut the grass. The bank obtained a default judgment against Carson. Even 16 months after the default judgment, the bank still had not scheduled the foreclosure sale. At this point, Carson filed a motion asking the court to deem the property abandoned and ordering a sale to occur within 5 weeks. Carson supported her motion with an affidavit admitting the abandonment and describing the property’s condition. The opinion does not explain why Ms. Carson filed the motion. However, I assume that she did not want any more fines from the city. She probably wanted the sale to cut off her liability to maintain the property. The local judge denied the motion, deciding that Ms. Carson didn’t have standing to ask the court to expedite the foreclosure sale date contrary to the desires of the bank.

On appeal, the Supreme Court took a hard look at Wis. Stat. § 846.102, the foreclosure statute that applies when a property is abandoned. The bank insisted that the statute allowed them to conduct the sale at any time within five years after the five-week redemption period. The Supreme Court rejected this view and determined that the procedures were mandatory, not permissive. The local court has the authority to order the bank to bring the property to sale soon after the five-week deadline despite any preference of the bank. The court stated that the trial court shall order such sales within a “reasonable” time after the five-week redemption period. The appellate court did not specifically define what a reasonable period of time would be. However, Mayor Barrett’s op/ed suggests that this means much less than 12 months.

The Supreme Court of Wisconsin stated that the statute was intended to “help municipalities deal with abandoned properties in a timely manner.” It is not clear whether foreclosure sales would be expedited by the courts’ case management procedures or on the motions of the owners, lenders, or municipalities. This opinion does grant Ms. Carson the relief she requested. However, it was mostly a victory for local governments in their crusade against the Zombie Foreclosure Apocalypse by shifting its burden to the banks. In cases where the borrower contests a finding of abandonment, this opinion might strengthen the hand of the locality and weaken the borrower’s ability to contest the foreclosure proceeding.

Justice David Prosser wrote a concurring opinion which agrees with the majority’s outcome. However, Justice Prosser remarked that “the majority opinion radically revises the law on mortgage foreclosure” by the following:

- The majority did not disavow the view that the local court’s authority to expedite foreclosure arises out of its power to hold parties in contempt of court. Owners should be concerned about broadening of courts’ discretion to impose sanctions on banks for not expediting foreclosure proceedings. Cases should generally be decided on their merits.

- Prosser observed that the plain meaning of the statute does not permit a municipality to bring an action to obtain the foreclosure sale because the statute limits the local government’s role to providing testimony or evidence. The new legislation AB 720 specifically gives the bank or municipality, but not the owner, standing to move for the property to be deemed abandoned. The government already has authority to foreclose for failure to pay property taxes. If the municipality also gets standing to intervene to expedite bank foreclosures, this raises questions about government intrusion into contract and property rights.

- Even with the majority’s opinion, nothing would stop lenders from thwarting the municipalities’ desire that they expedite foreclosures simply by delaying filing the foreclosure lawsuit to begin with.

- Prosser points out that other Wisconsin statutes provide standing to owners to petition the courts to exercise equitable principles to order a judicial sale of real estate. Ruling in favor of Carson in this case could have relied upon established principles of law instead of expanding substantive policy interests of municipalities at the expense of owners and banks.

Sometimes “solutions” to a short-term crisis can create greater problems later. In BNY Mellon v. Carson, the majority’s interpretation of the statute opens the door for potential abuse of foreclosure procedures. A bank or locality could try to use this improperly to quickly foreclose on a borrower who has a willingness and ability to rectify the loan default. A crack in a window, a delay in mowing grass, or a temporary un-occupancy should not be used as a pretext in order to expedite foreclosure.

The fundamental question posed by BNY Mellon v. Carson and AB 720 is who should bear the burdens of acquiring and holding these “zombie” properties. The banks’ interests in the properties are defined by the mortgage documents. They don’t want their rights to be diminished by the localities’ activities in the courts or legislature. The City of Milwaukee doesn’t want to budget to foreclose on properties it doesn’t want. Owners want to either save their home from foreclosure or give it up without facing more fines or HOA assessments. Justice Prosser’s concurrence appears to point to balancing these competing interests through the proven equitable principles that courts have applied to address crises for hundreds of years. Perhaps this can be used to protect the interests of owners. It will be interesting to see if Scott Walker signs the bill.

Laws provide local government with the power to foreclose on properties for failure to pay real estate taxes. If these localities want to expedite foreclosure, the could use those statutes or even lobby to have them streamlined. On March 1, 2016, the Virginia General Assembly enacted new legislation to address the issue of “zombie” foreclosures in the Old Dominion (thanks to Jeremy Moss & Leonard Tengco for alerting me to this). Senate Bill 414 authorizes local governments to create “land bank entities” that would use grants or loans to purchase, hold, and sell real estate without having to pay property taxes. These land banks can be set up as governmental authorities or nonprofit corporations. I’m interested to see how prevalent land banks will become and who will ultimately benefit from their participation in the real estate market.

UPDATE: Check out my April 23, 2016 “On the Commons” podcast with HOA attorney Jeremy Moss and Host Shu Bartholomew. We discuss the Zombie Foreclosure phenomenon and what it means for HOAs and owners.

Case Citation: Bank of N.Y. Mellon v. Carson, 2015 WI 15 (Wisc. Feb. 17, 2015).

Photo Credits:

MILWAUKEE via photopin (license)

Scott Walker via photopin (license)

April 4, 2016

HOAs Prepare for a Zombie Foreclosure Apocalypse

In the contemporary dystopia, property ownership provides ordinary people with space in which to live, work and play in peace, safety, and freedom. Americans also see real estate as an investment. My high school friend Tom was one of my first classmates to purchase a home. Years ago, he explained that the great thing about a home is that it is an investment and you also get to live in it. Unfortunately, there are many predators in the marketplace seeking to capitalize on consumers’ commitment to home ownership. Some loan servicers, debt collectors, and contractors see owners as opportunities. Their trade groups lobby state capitals. Owners have to stick up for themselves in Court and with their elected representatives to protect themselves from becoming someone else’s cash drawer. Sometimes unscrupulous people get what they want by conceptually framing a crisis to shape the perceptions of decision-makers. Fear is one of the easiest emotions to manipulate. Owners should be skeptical of how the housing industry describes the Zombie Foreclosure Apocalypse.

In a recession, financial struggles can render owners unable to make payment obligations to mortgage lenders and HOA’s. In many cases, these personal crises are temporary. Job loss or illness of the owner or a family member can cause a temporary but acute financial crunch. The problems may be fixable by a new job or resuming work after addressing a family member’s needs. Unfortunately, lenders and HOA’s tend to treat all defaults in payment obligations the same. In the past few years, HOA’s have waited for assessment income when banks delayed foreclosing on homeowners. In these so-called “zombie foreclosures,” banks delay completing foreclosures for years because there is little economic incentive to adding the distressed property to their own real estate inventory. If they buy the property, they become responsible for it as the new owner. Usually the owners stop paying their HOA dues around the time they can’t pay their mortgage. The HOA industry sees themselves suffering financial losses at the hands of loan servicers who fail to timely foreclose and put a new owner in the property with the willingness or ability to pay the HOA assessments.