February 25, 2014

Reel Property: “The Attorney” and the Appearance of Justice

(This post is the second and final part in my blog series about the 2013 South Korean film “The Attorney.” Part I can be found HERE)

“The appearance of justice, I think, is more important than justice itself.”

Tom C. Clark explained in an interview why he resigned as a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. President Lyndon Johnson wanted to appoint Clark’s son, Ramsey, as U.S. Attorney General. The Constitution does not forbid a father from sitting on the Supreme Court while his son heads the Department of Justice. Tom Clark observed that although his son may not have anything to do with particular D.O.J. cases before the Supreme Court, the public would associate the outcome of the cases with the father-son relationship. The public develops its perceptions of the justice system more from news reports than personal experience. These perceptions help form the rule of law.

Tom C. Clark explained in an interview why he resigned as a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. President Lyndon Johnson wanted to appoint Clark’s son, Ramsey, as U.S. Attorney General. The Constitution does not forbid a father from sitting on the Supreme Court while his son heads the Department of Justice. Tom Clark observed that although his son may not have anything to do with particular D.O.J. cases before the Supreme Court, the public would associate the outcome of the cases with the father-son relationship. The public develops its perceptions of the justice system more from news reports than personal experience. These perceptions help form the rule of law.

The 2013 Korean film “The Attorney” reminded me of Justice Clark’s interview. This film is loosely based on the 1981 Busan Book Club Trial. In that case, attorney Roh Moo-hyun, the future President of S. Korea, defended a young man against terrorism charges supported by a written confession procured by torture of the defendants. A few days ago, I blogged about the first half of this film which focused on the attorney’s success building a real estate title registration practice. Today’s post explores the court drama at the climax of the movie.

The 2013 Korean film “The Attorney” reminded me of Justice Clark’s interview. This film is loosely based on the 1981 Busan Book Club Trial. In that case, attorney Roh Moo-hyun, the future President of S. Korea, defended a young man against terrorism charges supported by a written confession procured by torture of the defendants. A few days ago, I blogged about the first half of this film which focused on the attorney’s success building a real estate title registration practice. Today’s post explores the court drama at the climax of the movie.

One evening, lawyer Song Woo-seok (pseudonym for Mr. Roh, played by actor Song Kang-ho) entertains his high school classmate alumni at a restaurant managed by his old friend Choi Soon-ae (Kim Young-ae) and her teenage son, Park Jin-woo (Im Siwan). Song gets into a drunken argument with a journalist who defends the motives of student groups protesting the 1979 military coup. Song is a high school graduate who studied for the bar exam at night after working all day on construction sites. He struggles to understand the students’ idealism. Choi and Park are disappointed and angry about the property damage from the fight at their restaurant.

In a later scene, Park Jin-woo attends a book club meeting, where female students flirt with him about romantic content in a novel. The authorities raid the meeting and secretly take the students, including Park, into custody. Mrs. Choi searches for him all over Busan, even visiting the morgue. After many days, the authorities informed her of Park’s pending trial for crimes against national security. Choi begs Song to defend Park. Song’s loyalty to Choi and his journalist classmate overcome his reluctance to accept a perilous, politically-charged criminal case.

1. Personally Investigate the Real Property Before Trial

When attorney Song and Mrs. Choi visit Park in jail, his fatigued body is covered with bruises. Song interviews Park and his co-defendants about their arrest and detention. They describe the sounds of the street they heard from inside the interrogation location. Song locates and explores the mysterious building.

When I started litigating real estate cases, attorney Jim Autry explained to me the importance of a discreet first-hand view of the property at issue, including value comparables supporting an appraisal. Song’s risky investigation of the decrepit building where the police conducted the interrogations reflect his real estate and construction background. This on-site investigation allows him to interpret the documents and witness statements and try the case with confidence.

2. Verdict Preferences Develop Before Conclusion of the Evidence

This trial drama defies a conventional legal analysis because the verdict appears politically predestined. Attorneys going to the theater to see taut repartee under the rules of evidence will be disappointed.

The case is tried without a jury. Beforehand, the judge privately requests that defense counsel refrain from making a lot of objections and motions in front of the news media. The judge makes several early evidentiary rulings against Song and the defendants. Everyone anticipates a show trial imposing the political will of the military junta.

Song bravely transforms the case into more than a show of power. In interrogation, the defendants signed confessions that they read British historian E.W. Carr’s “What is History?” in their book club. The prosecution presents an expert who testifies that this book is revolutionary propaganda. On cross-examination, Song shows that this is required reading in the leading universities in South Korea. Song also tricks the prosecution into admitting that the expert’s offices are in the same building as the government’s intelligence service. This challenges the independence of the expert’s opinions.

3. False Confessions

Song calls Defendant Park to testify. Park explains that he signed the confession after many days of torture by the police. When Song presents photographs supporting the witness’s testimony, the prosecution argues that the wounds were self-inflicted.

Even without torture, false confessions are a common problem in criminal justice. Virginia Lawyers Weekly recently reported that 1/4 of all convicted defendants later exonerated by DNA made false confessions. Feb. 17, 2014, “Untruth or Consequences: Why False Confessions Happen and What To Do.” “Good cop/ bad cop” routines intimidating young, vulnerable defendants often lead to “confession” of details introduced by law enforcement during interrogation. Id.

4. Effect of Visceral Reactions of Courtroom Observers on the Trial Proceedings

Park’s testimony about the torture techniques brings the courtroom audience of family members and local media to tears. The authorities replace the families on the next day with a mob seeking a guilty verdict. Song’s examination of the police detective is a failure. The officer evades Song’s questions and lectures him about the threat of terrorism.

Just as the defense seems to peter out, Song and Park get a big break. Song meets the army medic used by the interrogators to keep Park alive during the interrogation. The medic courageously resolves to testify for the defendants about the nature and extent of the injuries. Song’s journalist classmate agrees to contact international media organizations in a desperate attempt to put pressure on the authorities about the medic’s testimony. The outcome hinges on the admission and credibility of the medic’s testimony.

5. Conclusion

Hollywood court dramas indulge their audiences with conclusive vindication. “The Attorney” reminded me that a system of justice is always a work in progress. Song evolves from construction laborer to moneymaking genius to litigator. Finally he becomes a civil rights leader motivated and tempered by his training and experience.

Song voice seemed frequently shrill during the trial. Perhaps a Korean speaker can comment on whether this was persuasive or detracting.

When a case turns into an uphill battle, attorneys sometimes rationalize that, “This could be worse.” The defense counsels’ role in the 1981 Burim trial must have been one of these worst-case scenarios. Average trial lawyers succeed for their clients when they can marshal favorable law and facts through in a legal system that works well. “The Attorney” presents an extreme case showing how courage, intelligence, loyalty and tenacity can earn the respect of colleagues, and in rare cases, a nation.

Perhaps Justice Clark would have respected Roh’s commitment. The villains in “The Attorney” see the criminal justice system as a blunt weapon and propaganda medium for use against critics of the military coup. This ultimately undermines the credibility of the legal system and weakens the rule of law. Attorney Song’s courtroom theatrics aren’t to make money or to cloak his personal insecurities. He takes risks out of deep loyalty to his client. Truth, not bullying, enhances the “appearance of justice.”

February 20, 2014

Reel Property: “The Attorney” (Korean, 2013)

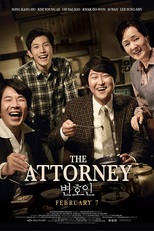

Before Roh Moo-hyun became a human rights advocate and President of South Korea, he was a lawyer in private practice. Director Yang Woo-seok loosely based the 2013 Korean movie The Attorney (Byeon-ho-in) on Mr. Roh’s early career. After a blockbuster run in S. Korea, “The Attorney” now appears in American theaters. On Presidents Day, my wife and I watched this film, coincidentally featuring a foreign president. “The Attorney” has his weaknesses, but captures what it means to be an advisor, entrepreneur and advocate.

Song Kang-ho plays lawyer Song Woo-seok, a fictionalized, young Roh. Mark Jenkins observes that “The Attorney” begins as a comedy about a pioneer in land registration practice in Busan, Korea. Like a lawyer changing focus mid-trial, director Yang shifts gears in the middle of the film. Song accepts the defense of a young waiter who, after brutal torture, “confessed” to fomenting overthrow of the government. See Mark Jenkins, Feb. 6. 2014, Wash. Post, “‘The Attorney’ Movie Review: An Earnest and Instructive South Korean Box-Office Hit.”

Part One of this blog series focuses on Song’s success building a residential settlements practice. Part Two will focus on his trial preparation and advocacy for victims of human rights abuse.

Part One of this blog series focuses on Song’s success building a residential settlements practice. Part Two will focus on his trial preparation and advocacy for victims of human rights abuse.

1. Don’t Give Up – Re-calibrate and Move On:

Song pulls himself by his boot straps by maintaining a positive outlook. Before Song conducted legal settlements of homes, he literally built them. When I watched this film, I personally identified with the title character. After a day on the job, Song washes the construction site grime off his hands and starts to study. Your humble blogger worked as a laborer for a construction company during his college years. Song studied law in the evenings in neighborhood restaurants and unfinished buildings. I attended law school in an evening program while working a normal day job. A few years ago, I discovered culinary gems in Northern Virginia’s Korean restaurants. The restaurant scenes in the movie made me feel hungry!

After dinner at a restaurant managed by Choi Soon-ae, Song skips out on the bill. The dinner money goes to buy back his pawned law books. Song motivates himself by writing “Never Give Up” on the textblock of his books and into concrete facades at work sites. Song has little education or money to support his family or pay his debts. He uses “Never Give Up” to reinforce a positive outlook in the face of adversity. Writing or sharing a constructive affirmation can overcome self-doubt or the negativity of others.

2. Fearless Niching & Frequent Networking:

After passing the bar, Song receives a judgeship. Struggling to support his family, he resigns to found a real estate registration practice. This practice is similar to that performed by title companies and settlement agents in the U.S. Song capitalizes on a rule change authorizing attorneys to do work previously restricted to notaries public. Initially, his bar association colleagues scorn him for doing work they consider beneath them. At a bar meeting, he overhears them gossiping as they sit down to eat at his table. They complain that he is out meeting people and handing out business cards. Unperturbed, Song introduces himself and hands out his cards.

After Song finds financial success, his rivals follow him into this practice area, competing for the same customers. He reinvents himself again as a tax law advisor. Song’s vision and lack of pretension distinguish him from his colleagues. He fit his own background and talents with a high-volume consumer practice. Years after failing to pay the dinner bill, the new attorney returns to Mrs. Choi’s stew-house to repay his debt. She refuses, with motherly joy for a prodigal patron, insisting that he become a regular customer.

“The Attorney” features a foreign legal system and a different culture. I relied on the subtitles to follow along. In spite of cultural and linguistic barriers, the first half of the movie shows universal entrepreneurial strategies. Another WordPress blogger, Seongyong, has great photos from the film in his post.

In the first part of the film, the director develops Song’s character as worldly, warm & family-oriented. In the second half, Song puts his career, reputation and safety on the line to oppose anti-terrorism charges based on confessions procured by torture of the client. Stay tuned to the next blog post!

February 14, 2014

George Clooney, Ken Shigley & Legal Case Selection

“Accept only cases you would be willing to take to trial.” Ken Shigley, past president of the Georgia Bar, included this in his 10 Resolutions for Trial Lawyers in 2014. There are millions of ways that lawyers convince themselves to accept a questionable case:

- “The case might lead to larger, stronger cases in the future.”

- “I’ll settle it if it seems weaker when I learn more of the details.”

- “The client seems to have an ability to pay.”

- “I don’t normally take these types of cases, but any generalist could handle it.”

- “I’ll withdraw if the client relationship deteriorates.”

Every client with a meritorious case deserves a lawyer committed to zealous advocacy. To the lawyer, the case represents an investment of time, reputation and firm resources. The larger the case, the greater the professional investment. Unfortunately, in a competitive marketplace, lawyers frequently feel pressure to accept cases that aren’t a good fit for them. However, it might be easier to agree to take a weak case than to favorably withdraw or settle it later.

In many ways, Shigley’s #1 Resolution applies to clients as well. A client may go to a lawyer with a problem. The lawyer may respond with questions, insights and a litigation proposal not anticipated by the client. Moving forward with a real estate lawsuit is usually a major decision, requiring substantial investment of time and resources that tends to escalate over the months or years prior to resolution. An expert faces the same challenges.

How does a client, lawyer or expert know whether she is willing to commit to take a case through trial (and beyond, if necessary)? This is particularly important in real estate cases where the remedy may involve more than an award of damages to one side or the other. Present and future property interests may be at stake.

In the movie theater, lawyers like fixer “Michael Clayton” or divorce attorney Miles Massey from “Intolerable Cruelty” have glib answers. George Clooney, the actor portraying both of these fictional attorneys, recently gave an interview with the Washington Post to promote his latest film, “The Monuments Men.” Ann Hornaday, February 6, 2014, “George Clooney Uses His Star Power to Keep Part of Old Hollywood Alive.” Although Ms. Hornaday seems too glowing at times in praise of Clooney, I agree with her basic assessment:

“There might not be another actor alive who so thoroughly personifies movie stardom, or deploys it so adroitly — as commodity, means of production and public trust.”

In the interview, Clooney describes how he learned the hard way which movie roles to accept or decline.

1. Choose the “Screenplay,” Not Just a Role:

In 1997, Clooney starred in “Batman & Robin,” an admittedly disastrous installment in an otherwise successful franchise: “Until [Batman & Robin], I had just been an actor . . . I had only been an actor in a TV series, and then I got ‘E.R.'” E.R. made Clooney a household name. Batman set his reputation back:

“And after I got killed for ‘Batman & Robin,’ I realized I’m not going to be held responsible just for the part anymore, I’m going to be held responsible for the movie. And literally, I just stopped. And I said, It now has to be only screenplay. Because you cannot make a good film from a bad screenplay.”

Prior to Batman, he simply looked at the part offered to him in a film. Batman taught him how being a leader or a star requires a larger commitment.

A lawyer must present his client’s case compellingly for the jury at trial. Preparing for trial requires roles: client representative, witnesses, testifying experts, jury consultants, first-chair litigator, second-chair litigator, legal assistant, general counsel, insurance counsel, and so on. The litigation equivalent to a screenplay is the outline containing all of the arguments, statements and examination questions. Unlike movies and T.V., a lawyer cannot script the behavior of any actor in the drama other than himself. Neither the lawyer or the client have a complete trial outline to go over in the initial client interview. At that point, the lawyer may receive some anticipated witness testimony and exhibit documents, but probably not all of the facts and issues. The initial case evaluation is extremely important. There is no better way to make a preliminary evaluation than in an opening memorandum.

The challenges of initial case evaluation illustrate the value of a specialized litigator to the client. Preparing a detailed proposal or opening memorandum is a feasible time investment to a professional in a niche. Reducing the initial case evaluation to a written summary allows the lawyer and client to visualize the proposed role within the larger “screenplay” and the likelihood of a win-win. BIind acceptance of larger roles in big budget matters may lead to a “Batman & Robin” result.

2. Leading a Team Through the Darkness:

Law schools do not focus on leadership and management in the core curriculum. Law firms typically structure around collegial authority, originations and billable hours. How can lawyers become great leaders and team-builders?

In addition to choosing films based on the screenplay, Clooney forged relationships with great directors such as the Coen brothers and Steven Soderbergh. In 2006, Clooney and his partners formed Smokehouse Pictures for the purpose of making movies missing from Hollywood’s contemporary repertoire. “We want it to be low-budget, dark, screwy…..We like that world a lot.” These personnel decisions may not be based on the easiest way to fill roles. Nor are they dependent upon celebrity and institutional relationships. Creative partnerships and budgets lay the groundwork for success.

3. The Lawyer’s Niche and Initial Assessment:

What can be learned from Ken Shipley and George Clooney’s resolutions? Neither of them say, “Only accept roles that guarantee or promise success.” The decision to accept or decline a role hinges on commitment to the project and others, especially the client. A litigator niched in a particular jurisdiction and practice area is best positioned to make this commitment. He is more prepared to develop a preliminary “screenplay” and draw from a network of other professionals.

photo credit: Josh Jensen via photopin cc

February 12, 2014

Court Sentences Son for Storing Inoperable Vehicles at Mom’s House in Harrisonburg

I grew up in a rural county in Virginia. Seeing broken-down cars parked in front of a house was part of the landscape. The perfect backdrop for the Blue Collar Comedy Tour. If you are waiting to get the money to fix it, where else would you store a car that doesn’t work?

In college, a friend of mine lent me his car. A tire went flat in a church parking lot. The church got tired of having a broken down car out front, week after week. The priest and I tried to change the tire. No matter how hard we pried, we just couldn’t get the wheel off. Later I learned from the owner that the wheels were welded on! I then felt like less of a wimp.

A car can be the apple of the owner’s eye. But when vehicles break down, they become an eyesore to the community. Many local governments have zoning ordinances against storing multiple inoperable vehicles outside homes without a covering screen or wall. Harrisonburg, Virginia, a college town in the Shenandoah Valley, has one of these ordinances.

The City of Harrisonburg convicted Terry Wayne Turner of violating a zoning ordinance by storing four inoperable vehicles on property owned by his mother. Terry owned the four vehicles. Although he lived with his mother, he did not own or lease her property. Harrisonburg cited him with a zoning violation for storing the four inoperable vehicles. Terry Wayne Turner v. City of Harrisonburg, No. 1197-12-3 (Va. Ct. App. Oct. 8, 2013)

At trial in the Circuit Court of Rockingham County, Terry argued that he was not liable under the zoning ordinances because he did not have title or lease to the property where he stored the cars. He argued that he was not a proper defendant in a land use case because the regulations apply to real property and their owners, not personal property like automobiles. The Court convicted Turner of a misdemeanor, ordered him to remove the vehicles and sentencing him to jail time and probation.

Mr. Turner appealed this conviction to the Court of Appeals of Virginia. He conceded that the storage of the vehicles rendered the property non-compliant with the land use restrictions. Turner focused on the fact that he was an invitee, and not an owner or tenant of his mother’s home. He argued that the scope of the zoning ordinances cannot extend to the ownership of personal property like automobiles. The Court of Appeals noted that zoning laws regulate the use and occupancy of land, not merely its lease or ownership. The ordinances do not contain specific limitations to owners or lessees of real estate. “Any person…found in violation of this chapter… shall be guilty of a class 1 misdemeanor.” The Court observed that if someone conducts a zoning violation on the property of another, that could thwart the purposes of land use restrictions.

On appeal, Mr. Turner brought up a new argument that his mother, not him, is the proper defendant in this case. She was the one who properly held a duty to make the property conform to the zoning regulations. The Court refused to consider this argument because Turner did not preserve it for appeal by presenting it to the trial judge. It is difficult from the text of the opinion to determine what role, if any, his mother played in this dispute. The Court may have found a belated attempt to shift the blame onto a family member unsavory.

Turner provides some food for thought:

- What renders a car “inoperable” for purposes of a zoning inspection? A road test? A log of how long it as been since it was moved? Removal of license plates or certain parts? Signs of wear?

- If buying a functioning car, paying for storage or taking the inoperable car for extensive repairs is outside a family’s budget, how can they maintain ownership of an automobile until they have the ability to repair it?

- Which is a greater eyesore in a residential neighborhood: (a) inoperable vehicles, or (b) walls or screens covering the area where they are parked?

- Can similar ordinances provide leverage against owners who abandon inoperable vehicles on commercial property?

- Generally, how far can zoning laws reach beyond the owners and improvements of the property to non-real estate matters before they infringe on civil liberties?

Terry Turner filed a Petition for Appeal with the Supreme Court of Virginia. As of this blog post, the Supreme Court has not yet decided whether to allow further appeal.

photo credit: lewsviews via photopin cc (Does not depict Mr. Turner’s vehicle – apparently this photo was taken in Rappahannock County)

February 5, 2014

They Might Be Mortgage Giants: Fannie & Freddie’s Tax Breaks

On January 3, 2014, the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau published a request for input from the public about the home mortgage closing process. 79 F.R. 386, Docket CFPB-2013-0036. The CRPB requested information about consumers’ “pain points” associated with the real estate settlement process and possible remedies. The agency asked about what aspects of closings are confusing or overwhelming and how the process could be improved.

The settlement statement is an explanatory document received by the parties at closing. The statement lists taxes along with other charges. The settlement agent sets aside funds for payment of both (a) the county or city’s property ownership taxes and (b) transfer taxes assessed at the land recording office. The property taxes are a part of a homeowner’s “carrying costs.” The recording taxes are part of the “transaction costs.” Typically, neither the buyer nor the seller qualify for a recording tax exemption.

The federal government advances policies designed to increase consumers’ access to affordable home loans. The Federal National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (“Freddie Mac”) provide a government-supported secondary market. They purchase some home mortgages from the lenders that originate them. The Federal Housing Finance Agency regulates these chartered corporations. In 2008, FHFA imposed a conservatorship over Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac.

In the years leading up to the crisis of 2008, Fannie and Freddie used their government sponsorship to purchase some of the higher-rated mortgage-backed securities. See Fannie, Freddie and the Financial Crisis: Phil Angelides, Bloomberg.com. As the secondary-market purchaser of these home loans, Fannie and Freddie have foreclosure rights against defaulting borrowers and distressed properties. These corporations participate in the home mortgage process from origination, through purchase post-closing, and, in many cases, subsequent foreclosure-related sales.

Congress exempts Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from state and local taxes, “except that any real property of [either Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac] shall be subject to State, territorial, county, municipal, or local taxation to the same extent as other real property is taxed.” 12 U.S.C. sections 1723a(c)(2) & 1452(e). Which local real estate taxes does this exception apply to? The ownership tax, transfer tax, or both? The statute does not specifically distinguish between the two. Fannie and Freddie concede that they are not exempt from the tax on property. However, they decline to pay the transfer taxes assessed for recording deeds and mortgage instruments in land records. This is one advantage they have over non-subsidized mortgage investors. Local governmental entities and officials from all over the U.S. challenge Fannie & Freddie’s interpretation of the exemption statute since it represents a substantial loss of tax revenue. This blog post focuses on two recent opinions of appellate courts having jurisdiction over trial courts sitting within the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Virginia:

Jeffrey Small, Clerk of Fredericksburg Circuit Court, attempted to file a class action against Fannie & Freddie in federal court on behalf of all Virginia Clerks of Court. Small v. Federal Nat. Mortg. Ass’n, 286 Va. 119 (2013). Mr. Small challenged their failure to pay the real estate transfer taxes. The Defendants argued that the Clerk lacked standing to bring the suit for collection of the tax. A Virginia Clerk of Court’s authority is limited by the state constitution as defined by statute. In the ordinary course of recording land instruments, the Clerk’s office collects the transfer tax at the time the document is filed. One half of the transfer taxes go to the state, and the other half goes to the local government.

To resolve the issue, the Supreme Court of Virginia found that if the taxes are not collected at the time of recordation, then the state government has the authority to bring suit for its half, and the local government to pursue the other half. The Virginia clerks do not have the statutory authority to bring a collection suit for unpaid transfer tax liability. Because they lack standing, the court dismissed the clerk’s attempted class action against Fannie and Freddie for the transfer taxes.

Maryland & South Carolina:

Montgomery County, Maryland and Registers of Deeds in South Carolina brought similar federal lawsuits challenging Fannie and Freddie’s non-payment of recording taxes. See Montgomery Co., Md. v. Federal Nat. Mortg. Ass’n, Nos. 13-1691 & 13-1752 (4th Cir. Jan. 27, 2014). The Fourth Circuit also hears appeals from federal Courts in Virginia. This case proceeded further than Mr. Small’s. The Appeals Court found that:

- Property taxes levy against the real estate itself. Recording taxes are imposed on the sale activity. The federal statute allows states to tax Fannie and Freddie’s ownership of real property. The statute exempts Fannie and Freddie from the transfer taxes.

- Congress acted within its constitutional powers when it exempted Fannie and Freddie from the transfer taxes, because this may help these mortgage giants to stabilize the interstate secondary mortgage market.

- The exemption does not “commandeer” state officials to record deeds “free of charge,” because the states are free to abandon their title recording systems. By this analysis, the exemption is not a federal unfunded mandate on state governments because the decision to include a land recording system as a feature of property law is not federally mandated.

Some federal courts in other parts of the country have reached analogous conclusions. e.g., Dekalb Co., IL v. FHFA (7th Cir. Dec. 23, 2013)(Posner, J.). This legal battle wages on in the federal court system, but the results so far favor Fannie and Freddie.

Discussion:

Is abandoning the land recording system a realistic option? In Greece and other countries lacking an effective land recording system, property rights are uncertain and frequently brought before the courts for hearing. See Suzanne Daily, Who Owns This Land? In Greece, Who Knows?, New York Times. Like Fannie & Freddie, land recording systems advance the policy interests of stabilizing private home ownership.

Fannie and Freddie aren’t required to pay locally collected recording taxes. Their “share” of the overhead for maintaining the land recording system come from other sources. This includes the recording fees paid by ordinary parties in real estate closings across the country. Does this give the mortgage giants an unfair competitive advantage over other institutional investors in the re-sale of foreclosed homes?

Are these differing tax treatments properly considered in the CFPB’s discussion about the “pain points” in closings? Settlement statements provide clarity regarding the charges listed. The transfer and property taxes assessed in real estate closings are confusing and overwhelming, in part because they represent hidden costs. These hidden costs include the exemptions afforded Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The purpose of these institutions is to help mortgage consumers. Should the tax loophole should be closed or the hidden costs be disclosed to consumers? Perhaps one of these change would advance the CFPB’s “Know Before You Owe” initiative.

photo credit: J.D. Thomas via photopin cc. (not particular to any of the cases discussed herein)