March 15, 2017

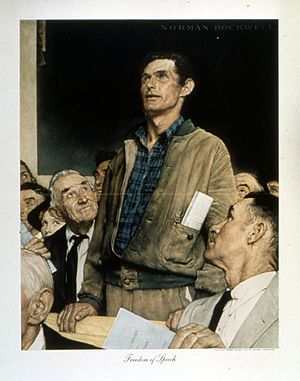

Should Homeowners Bring Complaints Against Contractors Before Courts or Regulators?

Property owners frequently have complaints about construction contractors. Some of these complaints involve thousands of dollars in damage or serious infringement upon the use or value of property. These property owners (and their attorneys) want to know who to turn to. Should homeowners bring complaints against contractors before courts or regulators? This question raises issues about how the government ought to enforce its laws and resolve disputes. There is a perspective that regulatory boards ought to be a welcome forum for owners threatened or damaged by alleged contractor misconduct. In this blog post I will explain why I believe that, for all its imperfections, the judicial system is the best venue for vindication of legal rights in consumer disputes.

In 2015, the Court of Appeals of Virginia decided an illustrative case arising out of a complaint of a home purchaser about the seller’s contractor. Around 2002, Mark Holmes purchased an Alexandria, Virginia home, including an addition constructed by Culver Design Build, Inc. Mr. Holmes was unhappy about defective construction of the addition. He went to the city government, whom the General Assembly tasked with enforcing the building code in his locality. The City Code Administration found extensive water damage caused by construction defects and issued a Notice of Violation to Culver. Holmes was not satisfied with Culver regarding corrective work, so he filed a complaint with the Virginia State Board of Contractors. Holmes asked the Board to suspend Culver’s license until it corrected the violation. Culver Design Build, Inc. argued that Holmes did not have legal standing to seek judicial review of the Board’s ruling because this was a license disciplinary proceeding. The Holmes case also includes issues about how deferential the courts should be to a licensing agency’s administrative rulings. This case is unusual in that Mark Holmes represented himself in his appeal to the Court of Appeals of Virginia. Mr. Holmes acknowledged that unlike the seller, he lacked the privity of contract with the contractor which potentially could be used to go to court in breach of contract. The Court of Appeals agreed with Culver and the Board for Contractors.

When homeowners conclude that a state-licensed contractor or tradesperson committed a wrongful act depriving them of their home or damaging its value, it is easy to see why the aggrieved party would want a governmental agency to help them. Most people deal with governmental agencies much more than courthouses or law offices. Lawsuits require significant commitments to pursue or defend. Public resources go to supporting various agencies that have apparent subject-matter authority. This may appear to be a taxpayer-financed legal authority to go after the professional. However, this strategy often does little more than aggravate the licensed professional, the agency officials and the consumer. The Holmes v. Culver case illustrates one key weakness with homeowners pursuing consumer complaints through the professional licensure and disciplinary board process.

When consumers are harmed by unprofessional conduct, usually what they want is to have the defect corrected, an award of money or the transaction voided. These kinds of remedies are conventionally handled in the court system. The professional regulatory boards focus on licensure. They consider whether a business is properly licensed, should the license be suspended or revoked, should fines be assessed, and so on. Prominent members of the industry typically dominate these boards. For example, licensed contractors sit on the Board for Contractors. Initiating a professional licensure proceeding is a clumsy means of advancing the specific interests of the consumer having a transactional relationship with the business. It is the judiciary that can grant money damages or other remedies arising out of the formation and any breach of the contract. Regulators focus on whether disciplinary action is warranted regarding the registration or licensure of the business. In the Culver Design Build, Inc. case, the Board for Contractors and the Court of Appeals for Virginia agreed that Mark Holmes did not have standing to contest a regulatory decision in favor of the contractor. The board had authority to punish Culver for failing to abate a regulatory violation. However, the board had no authority to order the contractor to take any specific action at the job site. The board did not deny Homes any right or impose upon him any duty in its decision, because its authority revolves around Culver’s licensure. It is the State Building Code Technical Review Board that has the authority to review appeals of local building code enforcement decisions, not the Board of Contractors. One of the appeals judges suggested that if Holmes’ contentions were taken to a logical conclusion, the new buyer of the house could have greater leverage over a contractor than the previous owner, whose remedies may be limited by the contract. In his oral argument, Mark Holmes admitted that trying to resolve his complaints through the Board of Contractors complaint process was, “cumbersome and very long lasting.”

Even if the consumer unhappy with an adverse decision made by a regulatory agency in response to a complaint has standing, her appeal to the courts may encounter other obstacles. The licensure dispute is unlikely to starts afresh on appeal. The courts tend to be receptive to the agency’s interpretation of the legislature’s statutes. In Virginia, courts accord deference to an agency’s reasonable interpretation of its own regulations (as adopted by the board pursuant to the statutes). A consumer’s ability to raise new factual issues may be strictly limited in her attempts to get the courts to overturn the board’s decision. Judicial deference to agency rulemaking is not without controversy. Judge Neil Gorsuch, whom President Trump nominated for the U.S. Supreme Court is a high-profile critic of judicial deference to agencies. In his August 23, 2016 concurrence to a federal appeals decision Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, Judge Gorsuch explained that concentration of both legislative and judicial power in regulatory agencies creates constitutional problems. The constitution protects the public from authoritarianism by separating the government by the type of power, not the subject-matter. Under the constitution, the legislature prescribes new laws of general applicability. Taken to its logical conclusion, doctrine that courts should defer to agencies’ quasi-judicial determinations of what the statutes mean unconstitutionally undercuts the independence of the judiciary. The constitutional problems identified by Judge Gorsuch are illustrated in the arena of housing industry occupational regulation.

Where does this leave an owner when property rights are infringed by regulated professionals? Should everyone should go back to renting? Certainly not! This is what the independent judiciary is there for. Usually owners have privity of contract with the contractor and do not need to go to an agency. They can sue for remedies for breach of contract or deceptive practices. Consumer advocates with an interest in legislation should focus on increasing access to the court system and not promoting an administrative process that may not be a good fit for the homeowner. If you find yourself needing to bring or defend a construction claim, contact my office or a qualified attorney in your jurisdiction.

Case Citations:

Homes v. Culver Design Build, Inc., No. 2091-13-4 (Va. Ct. App. Jan. 27, 2015) (Alston, J.)

HOMES V. CULVER DESIGN BUILD, INC. APPELLATE ORAL ARGUMENT

Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, No. 14-9585 (U.S. Ct. App. 10th Cir. Aug. 23, 2016) (Gorsuch, J.)

Photo Credit:

ehpien Old Town Alexandria via photopin (license)

February 28, 2017

Little Love Lost in Sedimental Affair

A lawsuit for damage to property must be timely filed to prevail in court. In Virginia, the statute of limitations for property damage is five years from accrual of the claim. When an owner suffers damage caused by a neighboring owner, when does this five year time-period start running towards its expiration date? Does the clock start ticking at the time the trespass or nuisance began or some other moment? On February 16, 2017, the Supreme Court of Virginia issued a new decision finding that when the effect of the offending structure is continuous, the claim accrues when damage began. The distinction between “temporary” and “continuous” is potentially confusing and the stakes are high in real property damage cases. Understanding how Virginia courts apply these rules is essential whenever owners and their attorneys discover what is happening.

Forest Lakes Community Ass’n v. United Land Corp. of America involved property that I have driven by numerous times. I grew up in Orange and Culpeper Counties in Virginia. My family would drive down Route 29 to shop or attend sporting events in Charlottesville. The Charlottesville area prides itself as the home of President Thomas Jefferson and the University of Virginia. Along Route 29 is Hollymead, an artificial lake built from a sediment basin. A sediment basin removes silt or other particles from muddied waterways. Two HOAs, Forest Lake Community Association, Inc. and Hollymead Citizens Association, Inc. jointly own Lake Hollymead.

The defendants included United Land Corp. and other owners and builders of the Hollymead Town Center (“HTC”) upstream from the Plaintiff HOAs’ lake. In 2003-2004, defendant developers constructed three new settlement basins along Powell Creek, the tributary to Lake Hollymead. Owners in the HOAs complained about excessive influx of sediment from the HTC construction into Lake Hollymead. If I bought a home with lake views, I wouldn’t like looking at muddied waters either. The HOAs complained that the defendants caused excessive sedimentation by improperly removing vegetation within the Powell Creek watershed.

If this was a serious problem, how did it get through the county’s permitting process? According to the case opinion, the development complied with state and local regulations regarding retainage of sediment within the three new basins. The county rejected suggestions from downstream owners that upgraded sediment filtration systems be required of HTC. The case doesn’t discuss whether the county’s standards did, or should set a benchmark for the reasonableness of the defendants’ control of sediment. Owners may have a right to sue even when the city or county refuses to intervene in a property damage dispute.

Discussions continued within these HOAs for years. In 2011 they finally filed suit, alleging nuisance and trespass. The HOAs asked for the court to award them money damages and an injunction requiring the defendants to stop the excessive drain of sediment. The HOAs enjoyed standing because they jointly owned Lake Hollymead as a common area. Incursion of sediment into Lake Hollymead began during HTC’s construction. The HOAs argued that intermittent storms caused subsequent separate and distinct sediment incursions, each triggering new causes of action that restarted the five year statute of limitation. This was contradicted by the HOAs’ expert who acknowledged that at least a little sediment incurred continuously. The HOAs also argued that the defendants’ sediment currently sits in Lake Hollymead and will continue to trespass until someone digs it out.

When a case comes to a lawyer for the first time, her initial assessment considers statutes of limitation. Legal claims have a corresponding statute of limitation setting a deadline by which the claim must be brought. Even if the claim is one day late it can be dismissed as time-barred. The HTC defendants sought to have the HOAs’ claims dismissed because they waited over five years after the sediment problem began in the 2003-2004 timeframe. After a day of testimony, Judge Paul M. Peatross found that the statute of limitations barred the claims because they accrued in 2003 and sediment incurred continuously thereafter.

The HOAs sought review by the Supreme Court of Virginia. Their appeal focused on Judge Peatross’ ruling that the claim was barred by the five-year statute of limitation because the continuous damage accrued at construction.

Justice D. Arthur Kelsey explained in the opinion that under Virginia law, a claim for an injury to property accrues when the first measurable damage occurs. Subsequent, compounding or aggravating damage attributable to the original problem does not restart a new limitations period. The court acknowledged that plaintiffs might need to seek a claim for an award for past, present and future damages. This accrual principle applies where the permanent structure causing the injury could be expected to continue indefinitely. I find this confusing, because drainage systems and sediment basins have lifespans. After a number of years, they fail or require repairs. Anything that comes into contact with water is under tremendous pressure. Perhaps what the court means is that the structure causing the injury is “permanent” if it would continue to cause the damage if maintained to continue to function as it did originally. This concept of “permanent structure” implies that its owner will maintain the nuisancing or trespassing feature as it presently exists.

Alternatively, in the facts of a case, a later cause of action might accrue that looks and acts like the earlier one but is a “stand alone” claim that starts a new five year limitations period. This can happen where the structure causes separate, temporary property damage. For example, some dams can be opened or closed. This exception can apply even when the physical structure causing the damage is a permanent fixture.

Justice Kelsey acknowledged the challenges applying these principles to particular cases:

Though easy to restate, these concepts defy any attempts at formulatic applications. Because the underlying issue – determining the boundaries of a cause of action – depends to heaving on the factual context of each case, our jurisprudence has tailored these principles to analogous fact patterns and rights of action.

To resolve these issues, the Supreme Court relied upon the factual finding of the Circuit Court that the three HTC sediment basins discharged into Lake Hollymead on a continuous basis and that the five year statute was not revived by a later, discrete discharge episode.

Ordinarily, on these motions to dismiss a lawsuit, the courts tend to give plaintiffs a benefit of the doubt. Often judges will look to see if the facts are contested so as to warrant a trial. Here, Judge Peatross took a day’s worth of testimony in a pretrial hearing. The HOAs may have appealed on the hope that the Circuit Court short-circuited the case too early and the Supreme Court would rule that they deserved another chance to have their case heard on its merits. This case may embolden more defendants to put on expert testimony in support of a plea of a statute of limitations in the hopes that their cases could be brought to a quick end.

The easiest way to avoid these kinds of statute of limitation problems is to file suit early enough so that either way the court looks at it, it would be deemed timely. Plaintiffs and their lawyers should file early to avoid the necessity of having to litigate such issues in day long evidentiary hearings and on appeal.

Case Citation:

February 6, 2017

The Surface Water Diversion Blame Game

According to the Bible, water is both the fountain of life and a destroyer by flood. Water naturally plots its own course, creating wetlands to store excess storm water. Human development, for better or worse, seeks to maximize the value of property and minimize land set aside for natural wetlands or artificial drainage purposes. The proximity of water can enhance or damage the value of real estate. For example, waterfront properties tend to fetch higher sale values. Sometimes neighbors will improperly channel water off their own land onto that of another in an effort to fend off unwanted surface water diversion. Lawyers and judges describe unwanted surface water as a “common enemy” because both neighbors seek to avoid it. The common law tradition developed a system of rules whereby judges can resolve disputes between neighbors over the reasonableness of surface water diversion.

Sometimes it is not a family or business that owns the uphill parcel that is diverting surface water. A property owner might find herself contending with a governmental or community association neighbor in a surface water diversion dispute. In a recent Southwest Virginia lawsuit, owner Consortium Systems, LLC sued two contractors, Lane Engineering, Inc. & W-L Construction & Paving, Inc. who constructed a sediment pond on a neighboring technology park owned by Scott County Economic Development Authority (“County EDA”). Rural counties like to build technology parks to attract out of town businesses to relocate there. Consortium alleged that the EDA’s contractors built the sediment pond without a proper outlet or outfall.

Owning property beside a public or private common area can be an advantage or a risk. Businesses want to locate themselves near parking, amenities and potential sources of customers or vendors. However, if a dispute arises between an owner and a governmental neighbor, the private party may find themselves facing additional legal obstacles. Sometimes governmental entities enjoy sovereign immunity, shortened lawsuit filing deadlines or additional notice procedures. Consortium tried to sue the contractors for negligence, trespass and negligent surface water diversion. The owner argued that the contractors should be liable to damage to neighboring properties because they faultily constructed the drainage facilities on the County EDA property. In his January 9, 2017 ruling on the contractors’ pretrial motions, Judge John C. Kilgore made findings illustrating an owner’s challenges to sue its neighbor’s contractors:

- Common Enemy Doctrine. Because surface water must go somewhere in developed areas, the common law tradition allows neighboring owners to “fight off” the “common enemy” onto neighboring parcels. Virginia, like many states, has an exception requiring surface water diversion to be done, “reasonably and in good faith and not wantonly, unnecessarily or carelessly.” Virginia courts find improper surface water diversion where the neighbor collects water into an artificial channel and redirects it onto someone else’s land.

- Sovereign Immunity. Virginia counties enjoy the sovereign immunity of the commonwealth. Municipal corporations are also entitled to sovereign immunity when exercising governmental functions. This immunity extends to contractors working for a governmental body. However, sovereign immunity does not protect the negligent performance of the government’s contractor. Judge Kilgore found the Economic Development Authority’s construction of the technology park to enjoy sovereign immunity without discussion in his opinion letter. Consortium’s negligence claims had been previously dismissed.

- Who is Responsible, the Neighbor or their Contractor? Judge Kilgore observed that the two defendants, Lane & W-K were working on behalf of the EDA. Generally speaking, the owner of a neighboring parcel is responsible for the acts of its representatives and contractors. The Court did not find authority for holding the neighbor’s contractor liable for the surface water diversion, in this situation.

The court previously dismissed Consortium’s claims for negligence as not being timely brought. In its January 2017 ruling, Judge Kilgore dismissed Consortium’s other claims, which were for trespass and diversion of surface water as barred by sovereign immunity.

The Consortium Systems, LLC v. Lane Engineering, Inc. case contains several surface water diversion takeaways in addition to the judge’s legal rulings. First, when flooding occurs, the suffering owner should investigate the causes and potential remedies for the drainage problem. Sometimes the answer is not obvious. In serious cases, this may require the assistance of an engineer or other expert. Second, all flooding problems should be addressed promptly before additional damage occurs. If a neighbor is to blame, they should be notified promptly. Third, the law may apply a standard of care that is different from what may appear as ground water diversion best-practices. The flooded owner or her attorney may need to consult HOA documents, covenants, deed restrictions, easements, county storm water management guidelines, state case law and other authorities to determine the parties’ relative rights and responsibilities.

Case Citation:

Consortium Systems, LLC v. Lane Engineering, Inc., 2017 Va. Cir. Lexis 2 (Lee Co., Jan. 9, 2017).

Photo Credit:

KevinsImages New 2016 drainage Juniper rd. via photopin (license)(does not depict any facts discussed in blog post)

January 13, 2017

Check Your Privilege, HOA

The attorney-client privilege is frequently misunderstood in the community associations context. When many owners request information, sometimes their board, board’s attorney or property manager asserts the attorney-client privilege. This may seem to obstruct their attempts to assess their property rights or how community funds are being spent. I recently had a conversation with a friend about an issue she raised at a HOA meeting. She asked the directors whether certain assessments were valid under the governing documents. The board consulted with their attorney, who answered them by e-mail. My friend suspected that the attorney advised the board that a judge would deem these assessments invalid. When asked, the board and their attorney refused to disclose the email, claiming attorney-client privilege (“ACP”). Since the board answers to the owners and the attorney works for the HOA, are the owners entitled to the attorney’s answering email? Does it make sense for any non-director owners to pursue copies of the attorney’s email?

In Virginia we have a court decision that addresses this issue that I will discuss. But first, let’s cover the basics. Anyone who deals with lawyers must understand how the ACP generally works. If an owner understands the ACP, she can more effectively pursue the information to which she is entitled and side-step unnecessary quarrels over confidentiality. This blog post will focus on the attorney-client privilege as applied by the courts in Virginia. The basic principles are similar in states across the country. Does this doctrine really allow boards to conceal important plans and communications in a shroud of secrecy? Not really, but it is often, baselessly asserted in many disputes, including HOA and condominium matters.

The purpose of the ACP is to encourage clients to communicate with attorneys freely, without fear of disclosure. This way attorneys can give useful legal advice based on the facts and circumstances known to the client. The Supreme Court of Virginia defines the ACP as follows:

Confidential communications between attorney and client made because of that relationship and concerning the subject matter of the attorney’s employment are privileged from disclosure, even for the purpose of administering justice . . . Nevertheless, the privilege is an exception to the general duty to disclose and is an obstacle to the investigation of the truth, and should be strictly construed.

The burden is on the party asserting the attorney-client privilege to show that it is valid and not waived. The privilege can easily be waived by disclosure of the communications to third parties. Waiver may be intentional or negligent, where the disclosing party failed to take reasonable measure to ensure and maintain the document’s confidentiality. Judges will consider waiver of privilege questions on a case by case basis. In general, the courts are reluctant to weaken the privilege by finding waiver in doubtful circumstances.

Contrary to popular belief, the privilege does not apply to every document or communication transmitted between an attorney and client. For example, if the client sends the lawyer corporate or business documents related to the facts of the case, those items would not be protected by the privilege by the mere act of transfer. It is quite possible that only the cover letter would be privileged. Generally, the privilege covers the seeking and delivery of legal advice.

Related to the attorney-client privilege is the “work-product doctrine.” The work product doctrine protects from disclosure the interview notes, office memoranda, internal correspondence, outlines, mental impressions and strategy ideas of the client’s lawyers prepared with an eye towards litigation.

When the client is an incorporated association and not an individual, questions arise as to which people function as the “client” as far as the privilege is concerned. Corporations can only act by means of their human representatives. This will often extend beyond the officers and directors of the corporation. Courts have found the privilege not waived when employees were privy to the communications. While the privilege is sacrosanct, it is narrow in scope and easily waived.

In Batt, et al. v. Manchester Oaks HOA, a group of owners challenged their board’s policy whereby parking spaces were assigned in a community where some townhouses had garages and others didn’t. Parking is a precious commodity. The plaintiff owners sought correspondence between the HOA’s leaders and their attorney. The owners asked the Circuit Court of Fairfax to order Manchester Oaks to produce the documents. They argued that the directors were fiduciaries of the owners and the suit asserted that the board acted inimically to the owner’s interests. In some other states, this is a judicially recognized exception to the ACP in some contexts. Judge Terrence Ney, who was highly respected within the local bar, declined to adopt the “Fiduciary-Beneficiary Exception” because that would “chill” communications between parties and their attorneys for fear the exchanges could be used against them in the future. I think he got this right. Properly understood, this does not infringe upon owners’ rights. Here’s why:

- Owners Need Boards to Act Competently. Owners need their boards to freely share their concerns with their attorney without fear that someone could later obtain the emails and use them against them. Community associations law is complex. For HOAs to work properly, boards need legal counsel to help them accomplish worthy goals while complying with the law and the governing documents. Owners need the HOA’s lawyer to tell the board what they can’t do, so that they can avoid doing bad things.

- The Director’s Fiduciary Duties Are Primarily Defined by the Governing Documents. If a fiduciary-beneficiary exception applies to a communication, that would be shown in the covenants, bylaws or perhaps a statute.

- The Board’s Lawyer is Not the Community’s Judge. When new owners visit HOA meetings and see directors defer to the association’s counsel on legal matters, this may lead to a misconception that the written opinions of the HOA’s lawyer are the “law of the land,” subject only to review by a judge. The opinions of the board’s attorney are simply her advice. Sometimes attorneys are wrong. Trial judges and appeals courts exist to make final determinations on contested legal disputes.

- “What Did the Board’s Attorney Advise” is Not the Best Question. This is really the most important point here. Requesting the HOA to disclose its attorney-client communications is not the best question to ask. Instead, the owner should ask the board to explain its authority to adopt or enforce a resolution. A HOA or condominium’s legal authority is public. It is written in a declaration, covenant, bylaw, statute, etc. The written legal authority and the official policy cannot be privileged. If the owner and board were to end up in litigation, sooner or later this would have to be spelled out in court. Chasing after what the attorney confidentially advised the board is not the direct path to solving the owner’s problem. If the board or its managers object on grounds of privilege when an owner asks them to point to the section in the governing documents that undergirds the policy, then the owner needs a lawyer of her own.

Ultimately the owners challenging the directors’ parking policy in the Manchester Oaks HOA case prevailed in Court, invalidating the board’s parking resolution. They didn’t need the attorney’s advice letter to achieve this. In other cases, owners don’t need to invade the board’s privilege, when it is properly invoked. However, it is very common for corporate parties to try to abuse the attorney client privilege in litigation. When someone invokes the attorney-client privilege in a HOA dispute, that is a good time to retain qualified legal counsel. If a party doesn’t back down when called out on an improper invocation of privilege, the dispute can be put before a judge. This “Check Your Privilege, HOA” blog post is the first in a series about how the attorney-client privilege is used and misused in the community association context. In future installments, I plan on discussing a couple hot topics. Does the Property Manager qualify as the client for purpose of the ACP or is it waived if the manager participates in the discussions with the attorney? Are the HOA’s lawyers’ billing statements protected from disclosure to the owners by the ACP or are they fair game?

For Further Reading:

Batt v. Manchester Oaks Homeowners Ass’n, 80 Va. Cir. 502 (Fairfax Co. 2010)(Ney, J.)(case reversed on appeal on other issues).

Walton v. Mid-Atlantic Spine Specialists, P.C., 280 Va. 113 (2010).

Michael S. Karpoff, “The Ethics of Honoring the Attorney-Client Privilege” (CAL CCAL Seminar Jan. 31, 2009)

Photo Credit:

December 12, 2016

Construction Defect Warranty Claims

Construction defect warranty claims are a frequent source of conflict between contractors and new home buyers. Builders feel pressure to get the purchasers through closing so they can pay their employees, subcontractors and suppliers. For the past few years there has been a severe shortage of experienced tradespeople and supervisors. This makes the contractor’s quality control efforts more challenging. Inexperienced buyers can get frustrated with delays. They may wonder what would happen if they try to back out of the deal. When consumer complaints about construction defects are not resolved amicably, the parties often find themselves pursuing or defending lawsuits or arbitration proceedings.

New home buyers feel pressure from the contractor and the circumstances of their lives to go to closing. Later, they may discover decreased responsiveness to their customer service inquiries to the builder. What should parties do to prevent construction defect litigation from becoming necessary? How are these cases won and lost? I took up these issues in an October 14, 2015 blog post entitled, “Common Misconceptions about Home Builder Warranties” On November 21, 2016, the Circuit Court of Norfolk, Virginia decided a case that provides some valuable insights for contractors and purchasers.

In April, 2007, Benjamin Bessant and Dorothy Horne contracted with Dey Street Properties, LLC for the construction of a new home in Norfolk, Virginia. The buyers got the standard new home warranty pursuant to Va. Code § 55-70.1. Dey Street impliedly warranted that the home was constructed in a workmanlike manner and free from structural defects for one year from settlement or possession. The implied new home warranty includes a strict requirement that the buyer give the seller written notice of the alleged defects. This notice must be properly submitted to the seller within the one-year warranty period.

During construction of the home, Mr. Bessant purchased $650 in floor tile out of his own pocket and delivered it to the jobsite for an upgrade. Unfortunately, someone stole this tile while Dey Street maintained control over the premises. Because Dey Street failed to complete the project by the agreed upon delivery date, Bessant and Horne had to stay in a hotel for three weeks. On August 15, 2007, the purchasers moved in.

Shortly after move-in, the purchasers discovered several construction defects. Bessant mailed Keith Freeman (principal of Dey Street) a notice letter on September 5, 2007. Not getting much of a response, on December 20, 2007, the purchaser’s attorney sent another letter, this one addressed to “Freeman Homes, Inc.” Enclosed with the attorney letter was the purchaser’s September 5, 2007 letter with the list of defects. Dey Street proceeded to do some warranty repairs.

Note the confusion regarding who the purchasers were dealing with. In the facts of the case, the purchasers signed a contract with Dey Street. However, many contractors provide consumers with different pieces of correspondence that have different business names. Judge David Lannetti found that the buyers only had privity of contract with Dey Street Properties, LLC. However, because Mr. Freeman also sent correspondence to Bessant on Freeman Homes, Inc. letterhead, the court found that notices actually received by Mr. Freeman put the Dey Street company on actual notice of the warranty claim.

These parties were not able to amicably resolve these construction defect damages issues. Bessant and Horne sued Dey Street. This family experienced some struggles preparing for trial. The homeowners had certain damages excluded from the jury because they failed to submit a timely expert witness designation. Also, the owners failed to disclose the details of certain defects in response to the builder’s pretrial discovery requests.

Judge Lannetti’s opinion only talks about certain items at issue post-trial: $1,500 for flooring defects, $200 for subfloor repairs, $2,000 for the drainage and concrete problems on the porch and $200 for a porch column. The owners also wanted reimbursement for the stolen tile and the hotel stays. I suspect that there were additional defects claimed in the lawsuit but because pretrial disclosure deadlines weren’t met, the owners were prejudiced to assert them at trial. For purchasers, properly documenting the defects and the estimates to repair is not always easy. In most cases this requires finding another contractor to assess and estimate it.

After a two-day trial, the jury returned a verdict of $15,000.00 in favor of the owners. After the jury returned its verdict, the contractor moved to invalidate or set it aside the jury verdict. First, Dey Street argued that the owners waived their implied warranty claim because the first notice letter was never received and the second one was sent to Freeman Homes, Inc. and not Dey Street Properties, LLC. Virginia law requires the purchaser to send the written notice letter to the seller by hand delivery with retention of a receipt or by certified mail. The court found the certified letter to Freeman Homes, Inc. to be sufficient. The court observed that the owner of Dey Street used Freeman Homes, Inc.’s name and address in correspondence to the buyer. At trial Mr. Freeman admitted on the witness stand that he actually received the second notice letter and its enclosures. The owners are lucky that Mr. Freeman did not simply deny receiving anything. Because they have the burden of proof, the owners should take care to follow all formalities required in the contract or statute so that they don’t have to rely upon their opponent’s moment of candor in court.

Dey Street also argued that the evidence was insufficient to support a verdict of $15,000.00. Judge Lannetti found this argument more persuasive. Since the implied new home warranty statute doesn’t say anything about negligent security for the tile or consequential damages like hotel room bills, those items were thrown out. The court could not figure out how the jury could possibly have added the remaining evidence of defect damages could total $15,000.00. The judge recognized in his opinion that he was not permitted to substitute his own independent assessment of damages for the jury award, and could only look to what the maximum verdict that the evidence would support. Judge Lannetti reduced the $15,000 verdict and entered a judgment against Dey Street for $3,900. A tough result for owners when their jury was convinced that they were owed much more. If larger dollar amounts were at stake I would not be surprised if the owners petitioned to appeal the case.

Lessons from Bessant v. Dey Street include the following:

- Who Are the Parties? Purchasers should be clear about what party they are in contract with so that they can correspond with and sue the proper entity. Contractors must take care to ensure that everything is done in the name of the contractor identified in the written agreement to avoid personal liability.

- Formalities of Notice. When lots of money are at stake, parties shouldn’t rely upon their opponents to follow through on oral demands or representations. Notice requirements in statutes should be carefully followed. Assume that at trial the judge will expect proof of notice and one’s opponent will deny receipt of the written notice.

- Use Professionals. Engage with a construction litigator and independent expert witnesses early so that legal formalities can be observed and deadlines met to maximize results.

- Be Prepared to Deal with Delays & Headaches. Purchasing a home that hasn’t been built yet can be an exciting, and even cost-saving means of acquiring one’s dream home. It also carries with it significant risks of delays, defects and added expenses which may be difficult to get reimbursed for.

When legal disputes appear on the horizon, contractors and purchasers should seek the assistance of qualified counsel to preserve and protect their rights.

Legal Authorities:

Va. Code § 55-70.1 (Implied warranties on new homes)

Bessant v. Dey Street Properties, LLC (Norfolk Cir. Ct. Nov. 21 2016)(link available to VLW subscribers only)

Photo Credit:

Jason OX4 B-R Corridor at Sunset via photopin (license)(disclaimer: does not depict anything discussed in blog article)

November 15, 2016

Attorneys Fees Awards Against HOAs

In this blog and in my law practice, I focus on practical solutions to clear & present legal dangers to property rights of owners of properties in HOAs, condominiums or cooperatives. Many raise questions about getting attorneys fees awards against HOAs. This is an interesting topic in community associations law, where the outcomes of many disputes have a direct or precedential impact on other owners in the community. In my last blog post, I discussed a couple of 1990’s Virginia court opinions where owners’ counsel used an old English common law doctrine to solve modern HOA litigation problems. The doctrine of “virtual representation” allows individual owners to bring to complaints of general concern without naming every owner in the community as a plaintiff or defendant. Where the actual, named parties to the lawsuit fairly represent the interests of other members who are too numerous to add to the court case, the judge can nonetheless render a decision that binds all impacted parties. For example, a “representative” owner may bring a court case challenging an election or the validity of board resolution and the final order binds all members impacted by the election or board action. The doctrine of “virtual representation” solves a couple obstacles to owners gaining effective access to the legal system.

Today’s post discusses the problem of “free-riders” who may reap a benefit from other owners virtually representing them and footing the bills. In litigation, HOA boards draw upon the benefit of insurance policies, loans or assessment income to finance their legal expenses. The board may protract the dispute in a desire for a precedential effect or to simply wear down the owner. There is a case presently before the Supreme Court of Virginia where an owner accuses her association of the latter. Martha Lambert had a claim for $500.00 for reimbursement for certain repairs she made herself that were the responsibility of Sea Oats Condominium Association, Inc. The board’s lawyers defended the claim with time consuming motions and discovery normally used in cases where the amount in controversy is much larger than $500.00. Ms. Lambert “won” in the Circuit Court of Virginia Beach on what the judge described as a “close call.” The judge told the owner’s lawyer he did a “magnificent job” and reasonably pursued the case. However, the court only awarded $375 in attorney’s fees out of the full $9,568.50 amount Ms. Lambert incurred in the case. The only reason Ms. Lambert didn’t get the full amount was because the trial judge wanted to make an attorney’s fees award smaller than the $500 principal judgment. The Supreme Court accepted the appeal to determine whether the statute allowing for “reasonable” attorney’s fees required the Circuit Court to reduce the award to an amount in a nexus to the principal judgment awarded. Lambert accuses Sea Oats of engaging in “stubborn & obstructionist tactics.” Kevin Martingayle, Counsel for Ms. Lambert describes the trial judge as punishing the homeowner for vindicating her rights and discouraging others from doing the same when necessary. At stake is whether one party can get away with not performing their covenanted obligations because a lawsuit would add insult to injury. Lawyers practicing in the community associations arena around the state will watch to see what the Supreme Court does with this case.

The outcome of Lambert vs. Sea Oats only appears to directly impact the association and Ms. Lambert. In other HOA lawsuits, the rights of other owners are directly impacted by the outcome. What if, hypothetically speaking, a condo association caused injury to an entire floor of condominium units. One owner decides to sue. A plaintiff may find herself shouldering the burdens of similarly situated owners (“free riders”) not joining the suit or otherwise helping to pay for the legal expenses incurred by the plaintiff. Under many HOA governing documents and state statutes, the prevailing party at trial is entitled to an award of reasonable attorney’s fees against their opponent. What about the portion of a prevailing owner’s legal expenses which is attributable to representing the interests of similarly situated fellow members who are not official parties to the lawsuit? Would this provide a separate basis for an award of attorney’s fees reflecting the realities of “virtual representation?”

Since the 19th century, Virginia’s common law tradition of judicial precedents protects representative plaintiffs from the burden of the “free rider” problem. In “virtual representation” cases, the prevailing party may recover in their attorney fee award for legal expenses incurred in achieving the common benefit:

It is a general practice to require, when one creditor, suing for himself and others, who may come in and contribute to the expenses of suit, institutes proceedings for their common benefit, that those who derive a benefit shall bear their proportion of the expense and not throw the whole burden on one. This is equitable and just. But it only applies to those creditors who derive a benefit from the services of counsel in a cause in which they are not specially represented by counsel. If a creditor has his own counsel in a cause, he cannot be required to contribute to the compensation of another. Stovall v. Hardy, 1 Va. Dec. 342 (1879), quoted in, DuPont v. Shackelford, 235 Va. 588 (1988).

Virginia courts apply this “common fund” doctrine in awarding attorney fee awards in creditor suits, securities lawsuits, civil rights cases, trust & estate litigation and other representative litigation. In 1999, the Circuit Court of Winchester applied it in the context of a dispute among members of a defunct nonstock corporation over the proceeds of liquidated assets. Most community associations in Virginia are incorporated under the Virginia Nonstock Corporation Act.

The Supreme Court of Virginia recognized that the common fund doctrine serves to eliminate “free rides” that would unfairly burden litigants in cases that directly impact a class of represented parties not retaining counsel in the lawsuit:

The essence of the common fund doctrine is that it would be unfair to permit one party to retain counsel, to file suit, to secure a benefit that all will share, yet to leave the full cost of the effort upon the one party who initiated the suit while others who will share the proceeds make no contribution. If others are to sit idly by and reap the benefits of one litigant’s labors, the idle parties should share in the cost of those labors. In short, the common fund doctrine is aimed at preventing “free rides.” See J. P. Dawson, Lawyers and Involuntary Clients: Attorneys’ Fees From Funds, 87 Harv. L. Rev. 1597, 1647 (1974), quoted in, DuPont v. Shackelford, 235 Va. 588 (1988).

The common fund doctrine extends beyond cases where there is an actual “fund” of money to included cases where there may be some sort of injunctive, declaratory or equitable remedy that does not have a specific dollar amount associated with it.

I am not aware of any published judicial opinions where a judge has considered the “common fund” doctrine in representative plaintiff litigation specifically involving HOAs or condominiums. However, the Property Owners Association Act and the Virginia Condominium Act provide for “prevailing party” attorney’s fees. Is there any reason why the common fund doctrine should not be applied to avoid free riding of representative plaintiff litigation against community associations? I see no obstacle to use of this doctrine for such in a proper case.

Update July 20, 2022:

I have a new 2022 blog post about Attorney fee awards in HOA and condominium law cases. “Awards of Attorney’s Fees in Community Association Litigation.” This blog post addresses the issue of attorneys fees in these cases more generally, with greater focus on the procedural aspects of such claims.

In 2017 I posted an article more particularly about the Lambert v. Sea Oats Condo. Ass’n, Inc. case, “Condo Owner Prevails on Her Request for Attorney’s Fees.”

Case Citations:

Du Pont v. Shackelford, 235 Va. 588 (1988).

Turner v. Yeatras, 49 Va. Cir. 395 (Winchester 1999).

Photo Credit:

Jason OX4 Il Radicchio at the Border via photopin (license)(for illustrative purposes – does not depict anything from any case discussed)

November 3, 2016

Lawsuits Against HOAs Potentially Benefit Other Owners

In many HOA disputes, only one (or a small handful of) owners desire to challenge board actions that negatively impact a larger class of owners in the community. If the court finds that the board action was invalid, then the court decision would materially impact everyone, not just the plaintiff owners and the HOA. Today’s post is about how plaintiffs lawsuits against HOAs potentially benefit other owners. Usually, a plaintiff must name everyone materially impacted by a potential outcome as parties to the lawsuit. Must a homeowner join all owners as plaintiffs or defendants in a lawsuit against a HOA seeking judicial review of a board decision? What flexibility does the law allow for one or more owners to bring a representative claim against the association to benefit themselves and other similarly situated owners? How should attorney fees be handled in cases with “free riders”? The answers to these questions show tools for owners to enjoy greater access to justice in community association disputes.

Mass claims by owners may be brought against community associations in several ways. A group of interested owners can split the cost for one law firm to sue on their behalf. Alternatively, owners may bring separate suits and have the claims consolidated in court. Filing a class action may be a feasible option in many states. Is there any other way that claims can be brought to benefit both the named plaintiffs and other similarly situated owners? Can this somehow make lawsuits against HOAs more affordable?

There are good examples of such representative actions in Virginia. Ellen & Stephen LeBlanc owned a house in Reston, a huge development in Fairfax County, Virginia. Reston is a locally prominent example of where the community association model largely replaces the town or city local government. Most Restonians live under a Master Association and a smaller HOA or condo association. Such owners must pay dues and follow the covenants for both the master and sub association.

There are good examples of such representative actions in Virginia. Ellen & Stephen LeBlanc owned a house in Reston, a huge development in Fairfax County, Virginia. Reston is a locally prominent example of where the community association model largely replaces the town or city local government. Most Restonians live under a Master Association and a smaller HOA or condo association. Such owners must pay dues and follow the covenants for both the master and sub association.

The LeBlancs owned non-waterfront property near Reston’s Lake Thoreau. In 1994, the Master Association decided that henceforth, only waterfront owners would be permitted to moor their watercraft directly behind their properties. This would substantially inconvenience the LeBlancs’ boating activities. The LeBlancs’ lawyer Brian Hirsch filed a lawsuit in the Circuit Court of Fairfax County challenging the validity of the master HOA’s decision on both constitutional and state law grounds. The association retained Stephen L. Altman to lead their legal defense.

Roger Novak, Judy Novak, Rex Brown and Dalia Brown all owned waterfront properties on this lake. These families did not want the LeBlancs or other non-waterfront Reston owners mooring their boats behind their houses. I can’t blame them for wanting a tranquil aquatic backyard all to themselves. The Novaks and Browns hired lawyer Raymond Diaz to bring a motion to intervene. The Browns and Novaks became parties to the suit. These intervenors asked the judge to force the LeBlancs to name all the owners in Reston as parties or dismiss the case for lack of necessary parties.

In general, a lawsuit must be dismissed if the plaintiffs fail to name all parties that are necessary for the case to be properly litigated. A suit on a contract or land record usually must include all parties named in the contract or instrument. The Novaks and Browns wanted to block people like the LeBlancs from enjoying mooring privileges on the lake. They wanted the LeBlancs to name all the parties subject to the covenants recorded in the registry of deeds for the Reston Association. If the LeBlancs had to litigate against the hundreds of owners, then the case could quickly become uneconomical, even if most were friendly. The Court denied the intervening parties’ motion, upholding an exception from well-established legal precedents in non-HOA Supreme Court of Virginia opinions:

Necessary parties include all persons, natural or artificial, however numerous, materially interested either legally or beneficially in the subject matter or event of the suit and who must be made parties to it and without whose presence in court no proper decree can be rendered in the cause. This rule is inflexible, yielding only when the allegations of the bill disclose a state of case so extraordinary and exceptional in character that it is practically impossible to make all parties in interest parties to the bill, and, further that others are made parties who have the same interest as have those not brought in and are equally certain to bring forward the entire merits of the controversy as would the absent persons.

The Circuit Court found this exception to apply:

In the case at bar, it is impracticable to join the estimated 400 to 500 homeowners surrounding Reston’s five lakes in this action. Likewise, the interests of these persons are the same as those of the parties to this action, and said parties are certain to bring forward all of the merits of the case as would the absent persons.

Hundreds of other owners are materially impacted by the case’s outcome. But this exception allows the case to proceed without adding them as necessary. Other individual owners are not barred from suing or become party to the LeBlancs’ case. The other owners weren’t necessary for the practical consideration of the sheer number of the affected class. The court found the LeBlancs sufficient to represent the case against the exclusive moorings rule, and the Novaks, Browns and the HOA competent to defend the board’s action favorable to the waterfront owners. The LeBlanc’s case was permitted to proceed without adding hundreds of affected owners. This “virtual representation” procedure is significant because the court’s ruling on the validity of the board’s resolution would affect all owners, not just the parties.

Hundreds of other owners are materially impacted by the case’s outcome. But this exception allows the case to proceed without adding them as necessary. Other individual owners are not barred from suing or become party to the LeBlancs’ case. The other owners weren’t necessary for the practical consideration of the sheer number of the affected class. The court found the LeBlancs sufficient to represent the case against the exclusive moorings rule, and the Novaks, Browns and the HOA competent to defend the board’s action favorable to the waterfront owners. The LeBlanc’s case was permitted to proceed without adding hundreds of affected owners. This “virtual representation” procedure is significant because the court’s ruling on the validity of the board’s resolution would affect all owners, not just the parties.

At trial, the Court upheld the Board’s decision to regulate boating activity on Lake Thoreau as a valid exercise of powers granted in the covenants. The LeBlanc’s case was dismissed. The Supreme Court of Virginia declined to reverse the decision. However, the principle that one or more owners can virtually represent the interests of a large class of homeowners in a contest over the validity of HOA rulemaking has not been overturned.

In 1996, the Circuit Court for the City of Alexandria applied the same principles in a homeowner challenge to a condominium election of directors. The Colecroft Station Condo Unit Owners Association Board asked the court to dismiss the judicial review of the election because not all owners were listed as plaintiffs. The judge rebuffed demands that all owners be added as parties, citing the same exception as used in LeBlancs’ case.

This exception that all materially affected parties need not be named as a plaintiff or defendant in the lawsuit is important to homeowners’ rights for several reasons. It gives an individual or small group of owners the ability to proceed with a lawsuit even when their neighbors might be friendly but uninterested in litigating. It gives owners another option when their rights are threatened and are not effectively redressed by board of directors’ elections or initiatives to amend the governing documents. Certain types of claims may be brought where class actions are not permitted or unfeasible. One brave owner could get a court to overturn an invalid board decision infringing upon the rights of many. This “virtual representation” doctrine advances the cause of homeowner access to justice in HOA and condo cases.

One challenge in these “virtual representation” cases is the notion of “free-riders.” The HOA’s attorney’s fees are paid for by the board’s accounts receivable: assessments, fees, loans and/or fines. Representative plaintiffs leading the challenge might find themselves “carrying water” for similarly situated owners who would stand to potentially benefit from the outcome of the case but aren’t paying lawyers. Is it fair for the challenging owners to pay for the legal work undertaken to achieve a benefit to both the plaintiff and the larger class? Are they entitled to an award of attorney’s fees reflecting the benefit conferred on behalf of other interested parties not named as plaintiffs? I will address this question in a future blog post focusing on the doctrine of “common fund” or “common benefit” in attorney fee awards and how this might apply in community association cases.

Case Citations:

LeBlanc v. Reston Homeowners’ Ass’n, 38 Va. Cir. 83 (Fairfax Co. 1995)

Cobble v. Colecroft Station Condo. Unit Owners’ Ass’n, 40 Va. Cir. 105 (Alexandria Cty. 1996)

Photo Credits:

pnyren35 20160131_Reston Trail Walk-187.jpg via photopin (license)

andrewfgriffith Flight Over the Town Center via photopin (license)

Bill Schreiner Dec15707 via photopin (license)

October 25, 2016

Virginia Consumer Protection Claims Against Contractors

There is a lot of litigation and arbitration in the construction contracting industry. Most of these cases are disputes over whether the contractor did the work and if so, whether it has been appropriately compensated under the terms of the agreement. Some construction disputes include allegations of deceptive practices. Virginia law approaches unprofessional practices in the construction contracting industry in two ways: First, construction contractors must obtain licenses to do business here. A builder is subject to professional sanction if the Board for Contractors finds that the conduct violated regulations. There is a fund managed by the board, from which unsatisfied claims may be paid if certain criteria are met. Second, owners, general contractors, subcontractors and other parties can bring lawsuits (or where agreed, arbitration claims). Can residential owners bring Virginia consumer protection claims against contractors? Parties unfamiliar with these rules often need help navigating the legal system to protect their rights.

VCPA & License Regulation:

In the 1970’s, the General Assembly adopted the Virginia Consumer Protection Act (“VCPA”). The main purpose of the VCPA is to make it easier for consumers (including homeowners) to bring legal claims against suppliers for deceptive practices. Before the VCPA, consumers had to prove fraud. Suing for fraud is attractive because a court may award attorney’s fees or punitive damages for fraud. However, fraud carries a higher standard of proof and many defenses that the consumer must overcome. In a proper case, the VCPA allows for tripled damages and attorney’s fees. The legislature has exempted certain types of real estate related business activity from the VCPA, including regulated lenders, many landlords and licensed real estate agents. What about contractors? Are contractors subject to professional regulation and exempt from the VCPA? Last month, the Circuit Court of Loudoun County considered this question in a lawsuit arising out of a residential custom contracting dispute.

Closing the Sales Process for the Custom Residential Construction Project:

On May 20, 2015, licensed contractor Interbuild, Inc. made a written agreement with Leslie & John Sayres for the construction of a large recreational facility on their property. The Sayres agreed to pay $399.624.00 for what would include a batting cage, swimming pool, exercise area and bathroom. According to the Sayres, they relied upon certain false representations by Interbuild in their decision to move forward with the contract. They allege that Interbuild told them the following:

- Interbuild had been established since 1981.

- The project did not require a building permit.

- The contractor already priced things out with subcontractors.

- Interbuild would supervise construction full-time.

- The project would be completed in 16 weeks.

- 4000 PSI concrete would be used.

- The building would be constructed upon an agreed upon area.

On October 20, 2016, attorney Chris Hill discusses this Sayres opinion in his Construction Law Musings blog. He observes that many of the alleged misrepresentations sound like things that would be specifications or terms of the contract. Hill raises concerns expressed by Interbuild’s lawyers that the Sayres complaint attempts to transform a breach of contract case into a fraud claim. I agree that this fraud in the inducement claim will be a challenge to pursue. However, I think that some of the fraud claims described in the Sayres counterclaim sound more like promissory fraud than anything else. Under Virginia law, promissory fraud occurs when one party makes a promise to the other that they have no intention of keeping, and the listener relies upon this empty promise to their detriment. In July, I blogged about this in the foreclosure context. If a false promise remains fraud even after reduced to a contract, then the Sayres fraud in the inducement claims make more sense.

Some of these alleged misrepresentations appear potentially more serious than others. While contract management experience is important, the Sayres contracted with Interbuild for a certain result. The experience was not an end unto itself. A missing permit could become a problem if the county later decided that the construction was not code-compliant and wanted substantial, costly corrections. The subcontractor pricing could become an issue if it could be proven that Interbuild was effectively unable to complete the job from the get-go. A contractor is required to provide adequate supervision regardless of what is represented. Rarely will you see a written agreement that absolves a contractor of this. In a proper case, courts will award damages for delay. However, the Sayres would have to prove that they relied upon the agreed delivery date. I suspect that this lawsuit is not about the Sayres inconvenience of continuing to exercise in a different place. The strength of the concrete raises serious structural questions, but would require proof by expert testimony. Building the project on the spot where the customer wants is indeed a fundamental issue. However, it might be shown that the location under the contract is unfeasible due to site conditions or that the difference is only slight. In general, the damages must flow from the misrepresentations. Courts are reticent to award a windfall to purchasers if the lies are of minimal consequence.

After paying most of the purchase price but before completion, the Sayres terminated the contract. Interbuild sued for work that was allegedly performed but not paid for. The Sayres filed counterclaims for fraud in the Inducement, VCPA and breach of contract.

Fraud in the Inducement:

Interbuild sought a court ruling on whether the Sayres could move forward with their fraud in the inducement and VCPA claims. The Contractor argued that the fraud claim should be thrown out. Interbuild maintained that the fraud claim was not proper because the customer only alleges that their expectations under the contract were disappointed. In its September 8, 2016 opinion letter, the Court dispensed with this argument, distinguishing between fraud inducing formation of the contract and fraud in the performance of the contract. The court found that the counterclaim clearly alleged that the misrepresentations were made to convince the Sayres to sign the contract. Because the alleged fraud occurred before the contract came into being, the claim is not alleging disappointed contractual expectations.

When legal disputes arise, owners and contractors frequently focus their attention on things that were most recently said or done. A contractor may be unhappy about an owner’s hands-on attitude about a project. Customers may take offense at the contractor’s customer service. However, the case might be about fraud in the inducement issues that come from the sales process. In the Sayres case, the judge allowed the fraud in the inducement claim to move forward.

The VCPA:

Interbuild adopted a different approach in its attempt to get the Sayres’ VCPA claim dismissed. The contractor argued that since it is subject to regulation as a licensee of the state contracting board, it is exempt from the consumer protection statute. While the VCPA does not specifically name contractors as exempt, it does exclude “any aspect of a consumer transaction which aspect is authorized under laws or regulations of this commonwealth. Va. Code § 59.1-199. Contractors are subject to state regulation by Va. Code § 54.1-1000, et seq. In his opinion, Judge Douglas L. Fleming, Jr. followed judicial precedents distinguishing between consumer transactions that are specifically sanctioned by law vs. those that are merely regulated. The absence of a prohibition of a particular practice does not constitute authorization of that practice. Since the professional regulations do not specifically cover the particular types of business practices at issue, this statutory exemption does not protect the contractor from suit. The court found that the alleged misrepresentations are the kind of practices that are actionable under the VCPA. This is consistent with other rulings made by Virginia courts in cases between consumers and construction contractors.

The VCPA also provides that a consumer may sue a contractor for not having a license. Interbuild argued that because it had an active contracting license it was exempt from the VCPA. Since Interbuild is subject to license revocation for conduct that violates professional regulations, that should be the sole remedy under the state statutes. Judge Fleming rejected this argument, observing that the state’s licensure regulations do not, “inferentially cloak licensed contractors with VCPA immunity if they are shown to have committed deceptive practices.” In short, a professional license does not include with it a privilege to engage in fraudulent behavior.

News reports frequently raise public policy questions about professional regulation. Each year, more occupations become subject to licensure requirements. Usually this means that the leaders in that industry regulate its participants by means of a state board. Too often, self-regulating industries use these boards to protect prominent members against competition. Consumers look to the boards for relief from predatory practices, but are often frustrated by the results. Interbuild’s arguments seem to appeal to this notion that as a licensee, its customers should have to go through the board if they want a special remedy. Bear in mind that there is a public demand for housing prices to go down. Builders have a more organized lobby than consumers regarding professional regulation and limiting liability for extra damages in lawsuits. Given market demands, I wonder how close the General Assembly is to exempting contractors from the VCPA. The construction industry provides many jobs to Virginia. However, I think that the public’s interests would not be served if quality and service were sacrificed for job creation and affordability concerns. A defect-riddled house is the most unaffordable of investments to its owner and doesn’t help the “property values” of others.

All the September 8, 2016 opinion decided was that Interbuild’s counterclaims may move forward in litigation. Even under the lower standards and enhanced remedies of the VCPA, claims based on deception are difficult to prove and obtain an award of damages.

When disputes arise over custom construction contract projects, the parties cannot rely upon the board of contractors or the county’s permitting office to advocate or mediate for them. When payment issues, construction defects or other disputes arise, the services of an experienced construction litigator are necessary to protect one’s best interests.

For Further Reading:

Photo Credit:

Phil’s 1stPix Too Many Tonka Toys? via photopin (license)

October 13, 2016

High Court Upholds Public Policies Against Restrictive Covenants

The issue of restrictive covenants often comes up in news or social media stories where a HOA or condominium demands that an owner take down an addition, a shed, a statue or some other architectural feature on the grounds that it offends the rules. The board claims that the rule is found in (or derived from) a document recorded in the land records encumbering all of the properties in the community. The board’s assertion of the restriction may come as a surprise to the owner. In a recent blog post, Does an HOA Disclosure Packet Effectively Protect a Home Buyer?, I wrote about how the existing legal framework fails to adequately disclose to the purchaser what it means to live in a HOA. That post started some great conversations with attorneys, realtors and activists about how consumers could be better protected during the sale process. Today’s post focuses on what the legal requirements are for a contractual relationship to arise between the community association and a resale purchaser who did not sign off on the restrictive covenants originally.

Restrictive covenants that bind future owners are a legal device that predate HOAs and condominiums by hundreds of years. Community associations derive their power to collect $$$ from and enforce rules against their owners through restrictive covenants. However, many owners are not aware that enforcement of restrictive covenants are disfavored by Virginia courts on public policy grounds.

Restrictive covenants are contract terms which, if enforceable, follow the property or the person around even after the contract between the original parties is over. They aren’t limited to real estate. For example, a pest control company may ask an employee to sign an agreement not to compete against the employer even after leaving the company. Courts are skeptical of contracts that restrict the ability of a worker to make a living in the future. For public policy reasons, workers should be able to reasonably put their skills to use in the marketplace regardless of what a written agreement might say. The courts enforce only very narrowly tailored covenants-not-to-complete in the employment context. Judicial precedent and the uncertainties of litigation make many businesses reluctant to sue former employees now working as rivals.

Courts disfavor restrictive covenants on real estate for similar policy reasons. Covenants that bind future owners narrow the usefulness of the property. Labor and property should be freely marketable without short-sighted, unreasonable restrictions. Such a policy protects property values and market liquidity.

The Supreme Court of Virginia still shares this viewpoint. On February 12, 2016, the Court decided Tvardek v. Powhatan Village HOA. That case was about the validity of an amendment to the HOA declaration, including its restrictive covenants. In ruling in favor of the homeowners, the Court reaffirmed the strict construction of covenants that run with the land, even in contemporary HOAs. Justice D. Arthur Kelsey’s opinion explains:

“The common law of England was brought to Virginia by our ancestors” in large part “to settle the rights of property.” Briggs v. Commonwealth, 82 Va. 554, 557 (1886). At that time, English common law had developed a highly skeptical view of restrictions running with the land that limited the free use of property. “Historically, the strict-construction doctrine was part of the arsenal of restrictive doctrines courts developed to guard against the dangers imposed by servitudes.” Restatement (Third) of Property: Servitudes § 4.1 cmt. a (2000).

Virginia real estate law generally views restrictive covenants as a threat to liberty. University of Virginia law professor Raleigh Minor prophetically wrote in his 1908 treatise, “perpetual restrictions upon the use of land might be imposed at the caprice of individuals, and the land thus come to future generations hampered and trammeled.” If only Professor Minor could see how property rights have eroded in many communities today.

The viewpoint of many people in today’s real estate industry and local governments is the opposite of what courts have traditionally held. Buyers are told that covenants protect their investments from barbarian neighbors who might do something to make the surrounding properties look undesirable. But as Professor Minor pointed out 100 years ago, these rules give an opportunity for capricious enforcement. Is the message of our contemporary industry an insight misunderstood by previous generations, an appeal to the preferences of certain buyers who dislike non-HOA neighborhoods or merely a sales pitch?

English common law recognized very few restrictive covenants running with the land. Those receiving judicial approval appeared to be limited to easements appurtenant “created to protect the flow of air, light, and artificial streams of water.” United States v. Blackman, 270 Va. 68, 77, 613 S.E.2d 442, 446 (2005); see also Tardy v. Creasy, 81 Va. 553, 557 (1886). Over a century ago, we noted that “attempts have been made to establish other easements, which the [historic common] law does not recognize, and to annex them to land; but the law will not permit a land-owner to create easements of every novel character and attach them to the soil.” Tardy, 81 Va. at 557. Since then, in keeping with our common-law traditions, Virginia courts have consistently applied the principle of strict construction to restrictive covenants.

The court applied this principle in the Tvardek case where the association sought to enforce an amendment to the declaration against certain owners who didn’t vote for it. As the court reaffirmed in this 2016 decision, restrictive covenants are not always enforceable. The Tvardeks opposed being deprived of their right to rent out their property. The covenant has to fall within a recognized category. The principle of “strict construction” works against the restrictor and to the benefit and protection of the owner.

A restrictive covenant running with the land that is imposed on a landowner solely by virtue of an agreement entered into by other landowners who are outside the chain of privity would have been unheard of under English common law. See generally 7 William Holdsworth, A History of English Law 287 (1925) (“Whether or not the burden of other covenants would run with the land, and whether or not the assignee of the land could be sued by writ of covenant, seem to have been matters upon which there is little or no mediaeval authority.”). Privity has long been considered an essential feature of any enforceable restrictive covenant. Bally v. Wells (1769) 95 Eng. Rep. 913, 915; 3 Wils. 26, 29 (“There must always be a privity between the plaintiff and defendant to make the defendant liable to an action of covenant.”). Many of our cases have recognized this common law requirement. See, e.g., Beeren & Barry Invs., LLC v. AHC, Inc., 277 Va. 32, 37-38, 671 S.E.2d 147, 150 (2009); Waynesboro Village, L.L.C. v. BMC Props., 255 Va. 75, 81, 496 S.E.2d 64, 68 (1998); Sloan v. Johnson, 254 Va. 271, 276, 491 S.E.2d 725, 728 (1997). We thus approach the statutory issue in this case with this historic tradition as our jurisprudential guide.

Someone is “in privity” with another if they have legal standing to sue them because he (or his predecessor-in-interest) was party to the contract that creates the rights at issue. The court affirmed the common law privity requirement, rejecting any suggestion that it should be discarded as outdated. For this reason, the legal requirements that the association disclose certain documents and the seller honor a right of cancellation of the purchase contract have the effect of establishing privity between the HOA and the subsequent purchaser. Do these statutes fairly balance the respective rights of resale purchasers and community associations?

The Tvarkeks did not contest that they were not bound to the HOA covenants that existed when they bought their home. Instead, they sought to have an amendment to the covenants declared invalid because the statutory procedures were not properly followed. If you are curious about the technical reasons why the court found this particular amendment invalid, there are other bloggers, such as Jeremy Moss, following community associations law developments in Virginia have written about Tvardek from this angle. An HOA may have hundreds of members. The membership changes every year. Most owners have never personally made any transactions with the developer or the owners who voted to amend the declaration of covenants. How can privity exist if the declaration can be amended without a signature from every owner? That’s where the legislature comes into play:

The Virginia Property Owners’ Association Act, Code §§ 55-508 to 55-516.2, expanded the concept of privity considerably beyond common-law limits. In general terms, the Act permits the creation of a restrictive covenant running with the land and enforceable against subsequent owners of the parcels covered by the declaration, whether or not they consent, so long as the association follows the statutorily prescribed procedures governing the association’s declaration and amendments to it.

The enactment of the HOA statutes do not wipe out the rule of strict construction of covenants that run with the land. Instead, the General Assembly expands certain exceptions to the privity requirement for the enforceability of restrictive covenants. The basic rule of skepticism holds. The Property Owners Association Act must be understood within the context of the common law.

One might think that the modern age of statutes would have marginalized the role of English common law, but this is not so. “Abrogation of the common law requires that the General Assembly plainly manifest an intent to do so.” Linhart v. Lawson, 261 Va. 30, 35, 540 S.E.2d 875, 877 (2001). We do not casually presume this intent. “Statutes in derogation of the common law are to be strictly construed and not to be enlarged in their operation by construction beyond their express terms.” Giordano v. McBar Indus., 284 Va. 259, 267 n.8, 729 S.E.2d 130, 134 n.8 (2012) (citation omitted). A statute touching on matters of common law must “be read along with the provisions of the common law, and the latter will be read into the statute unless it clearly appears from express language or by necessary implication that the purpose of the statute was to change the common law.” Wicks v. City of Charlottesville, 215 Va. 274, 276, 208 S.E.2d 752, 755 (1974).

Case law is very important to make sense of any HOA. Otherwise the statutes just seem to be an enablement of legal powers for the boards that are not found in the governing documents.