October 31, 2019

Appeals Court Deems Association Street a First Amendment Public Forum

Disputes between individuals and HOAs frequently occur on the roads or sidewalks owned by the Association. The rights of way are usually the HOA’s largest budgetary and operational responsibility. The lot owners and their invitees rely upon the roads to access properties. State and local governments benefit financially by shifting the maintenance burden of the roads, sidewalks and drainage features onto an association that assesses dues on lot owners. Despite this public function, many associations or their residents want to use the roads’ “private” status to exclude undesired visitors or limit the roads’ use by lot owners. Representatives of the board may accost visitors as unwelcome. Managers may try to stop owners from communicating with residents on the sidewalks.

The declaration of covenants will contain provisions that define the respective rights of owners and the board with respect to common areas such as right of ways. By deed or “contract,” a lot owner may find that she has rights or duties with respect to these private roads that vary in scope or character from government-owned streets. However, owners are not the only parties that use HOA roads. HOA boards and committees are not the only authorities that regulate use of land in subdivisions. While the answers to most HOA problems are in the governing documents, sometimes broader legal principles apply. When do courts treat HOA roads or common areas as public forums for purposes of free speech analysis under the Bill of Rights? In July 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit considered such a case.

5325 Summer Avenue Property Owners Association, Inc. owns Virginia Run Cove, a two-lane asphalt street in Memphis, Tennessee. The public uses Virginia Run Cove to access a gas station, a church, a federal government office, and, since May 1, 2017 a Planned Parenthood Clinic. John Brindley, who does not live or work in this subdivision, decided to stand on this private street near Planned Parenthood’s parking lot to share with others his pro-life, anti-abortion message. In his Complaint, Brindley explained that he wanted to speak with Planned Parenthood patrons about alternatives to abortion without having to shout at a distance. His Complaint states that he wanted to share his views about abortion, as informed by his religious faith, in a nonviolent and non-harassing manner. Planned Parenthood complained to the Memphis police department that Mr. Brindley was trespassing on a private street in front of their business. The police arrived. Based on Planned Parenthood’s explanation that this was private property, they instructed Brindley to relocate. Under fear of arrest, Brindley left.

Mr. Brindley filed suit against the City of Memphis and representatives of its police department for infringing upon his First Amendment rights because Virginia Run Cove functions as a “public forum” for purposes of Free Speech analysis under the Constitution. Mr. Brindley did not name Planned Parenthood or the Association as co-defendants.

The case went up to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals after the federal trial-level court denied Mr. Brindley’s motion for a preliminary injunction.

On appeal, the outcome turned on how “public” Virginia Run Cove is for purposes of the First Amendment. Brindley contended that the road was a “traditional public forum,” requiring the court to strictly scrutinize governmental restriction on speech activities. The City of Memphis contended that it was a non-public forum, and the courts ought to defer to the police department’s actions.

Under federal case law, there is a strong presumption that public streets are traditional public forums. Also, the Supreme Court has held that a street does not lose its status as a traditional public forum simply because it is privately owned. If the street looks and functions like a public right of way, it suffices as a traditional public forum regardless as to who may hold ownership of it. The emphasis in this analysis is on how the road, sidewalk, park or other public space functions in the daily commerce and life of the neighborhood

The District Court for the Western District of Tennessee denied Brindley’s Motion for a Preliminary Injunction. The District Court Judge wrote:

When property is privately owned, it is subject to the First Amendment in proportion with the owner’s authorization of public use. “The more an owner, for his advantage, opens up his property for use by the public in general, the more do his rights become circumscribed by the statutory and constitutional rights of those who use it.” Marsh, 326 U.S. at 506. Inversely, where a property owner invites the public for a more limited use, reflected in a utilitarian design facilitating only the specific commercial purpose of the invitation, the balance tips in favor of the owner, as the limited invitation results in the retention of some of the property’s private nature. See Lloyd Corp. v. Tanner, 407 U.S. 551, 569 (1972).

Brindley v. City of Memphis, 2:17-cv-02849-SHM-dkv, 2018 U.S. Dist. Lexis 117481 (W. D. Tenn, Jul. 13, 2018)

The district judge denied the motion on the grounds that at the hearing, Brindley failed to carry his burden of establishing that the present or historic uses of Virginia Run Cove made it a “traditional public forum.”

On appeal, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals took up the question of how “public” Virginia Run Cove is for purposes of the First Amendment. Brindley contended that the road was a “traditional public forum,” requiring the court to strictly scrutinize governmental restriction on speech activities. The City of Memphis contended that it was a non-public forum, and the courts ought to defer to the police department’s actions.

Under federal case law, there is a strong presumption that public streets are traditional public forums. Also, the Supreme Court has held that a street does not lose its status as a traditional public forum simply because it is privately owned. If the street looks and functions like a public right of way, it suffices as a traditional public forum regardless as to who may hold ownership of it. The emphasis in this analysis is on how the road, sidewalk, park or other public space functions in the daily commerce and life of the neighborhood or community. The Sixth Circuit summarized the judicial opinions regarding whether a private street is a traditional public forum according to a two-part test: (1) is the privately-owned street physically indistinguishable from a public street and (2) does the street function like a public street. If both of these criteria are met, it is a “traditional public forum.” The Sixth Circuit observed that Brindley did not need to prove the past and present history of the use of Virginia Run Cove because consideration of its objective characteristics is sufficient. The appeals court arrived at a different result because it applied the First Amendment with greater generosity than the trial-level court.

The Sixth Circuit reversed the District Court. The appeals court found Virginia Run Cove physically indistinguishable from a public street. There were no signs or visual indicators that it was privately owned. The Court also found that the Cove functioned like public streets in the way it gave cars and pedestrians access to the businesses on that street. The City of Memphis argued that Virginia Run Cove was distinguishable from a public street because its street sign was blue, unlike the green signs used for public streets. The Sixth Circuit found that this open but subtle indicator to be insufficient to make Virginia Run Cove “distinguishable” as a nonpublic forum. This suggests that the “indistinguishable” requirement is not a rigid one.

The Court considered the effect of recorded land instruments. Under the Constitution, courts do not defer to state-law definitions whether the street is a publicly dedicated right of way to decide whether it is a traditional public forum. However, if such a dedication exists, that may be used in support of a free-speech argument. The final plat of the development contained a certification of dedication of the streets for public use.

The Sixth Circuit found that Virginia Run Cove is a “traditional public forum” for First Amendment purposes. The City admitted that under a strict scrutiny standard, they could not identify a compelling governmental interest in excluding demonstrators. The appeals court reversed the denial of the preliminary injunction and remanded the case to the District Court. On October 15, 2019, the District Court entered a consent order enjoining the city of Memphis police from infringing upon Brindley’s constitutionally protected right of self-expression on Virginia Run Cove.

Notice that the HOA was not party to this lawsuit. The complaint and opinion don’t mention HOA involvement. However, this case illustrates how the legal status of HOA common areas affect the rights of visitors and residents. This can be confusing if someone tells a visitor that they must leave because the right of way or common area is “private property.” Bill of Rights protections might not apply. This is further confused by the fact that HOAs often enjoy status as a tax-exempt entity because they perform a public benefit by maintaining roads, playgrounds and other public open spaces that would otherwise fall upon the government. HOA roads, easements and playgrounds are commonly used by persons who don’t reside or work in the community.

When people feel threatened in the HOA or condominium setting, they often call the local police department. While the police may have the authority to detain, arrest or summon someone under certain circumstances, they may not want to get involved in neighbor disputes. Also, the accused will have constitutional protections against governmental officers not ordinarily available in civil disputes. Its often unclear to whom an aggrieved party ought to state their claims in the event of a dispute involving an association.

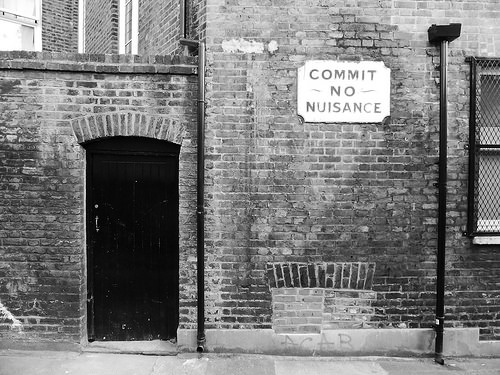

The growing body of case opinions defining privately owned roads or other open spaces as “traditional public forums” shapes the way that developers and HOA boards treat common areas and rights of way. Desires to have the government take over maintenance of roads for financial reasons runs contrary to restrictions on use for free speech. HOA boards may erect signage viewable to the public that may not be consistent with the terms of recorded instruments regarding the road or other common area. In fact, in some subdivisions, people may make a road or open space appear private when in fact the land instruments show that it is publicly dedicated. The signs may suggest that land is controlled by the HOA as a common area when in fact it is part of lots.

The City of Memphis did not attempt to appeal the adverse decision up to the U.S. Supreme Court. I see nothing to suggest that the Brindley case was incorrectly decided on appeal. This is good news, because every year more and more rights of way and park-like open spaces are developed as common areas of HOAs and condominiums. Citizens ought not to lose recourse to protections for speaking with others on public forums because they are developed as privately-owned land.

Judicial Opinions Discussed:

Brindley v. City of Memphis, 934 F.3d 461 (6th Cir. 2019).

Brindley v. City of Memphis, 2:17-cv-02849, 2018 U.S. Dist. Lexis 117481 (W. D. Tenn, Jul. 13, 2018).

October 24, 2019

Do I Even Have a HOA?

It’s usually clear to home buyers whether a HOA governs their subdivision. A well-maintained sign adorns the entrance. The community manager emails the buyer’s agent an official-looking disclosure packet. For many other landowners, especially in rural areas, it is not clear at the settlement table whether any HOA is active. Months or years after purchase, the owner may receive mysterious notices in the mail with demands to pay money or correct architectural features. This can come as an unpleasant surprise. The landowner may wonder whether this board or committee is for real or a rogue nonprofit. Does the owner have to obey the assessment or violation notice or can it be discarded as junk mail? The truth may not be revealed in the envelope enclosing the notice. The answer to this question is found by ordering a current title report for the property which will pull up all the declarations, easements, master deeds, amendments, plats, etc. This article focuses on problem solving for owners of lots in subdivisions. Questions about whether various legislative or bureaucratic acts are sound public policy fall outside the scope of today’s blog post.

Virginia courts treat the declaration of covenants as the “contract” to which all the lot owners and HOA are party. Recorded instruments may govern a lot even if the current owner didn’t sign anything, so long as the developer caused the covenants to encumber the subdivision. Courts enforce restrictive covenants where the intention of the parties is clear, and the restrictions are reasonable. In Virginia, restrictive covenants deemed doubtful or ambiguous are construed against the party seeking to enforce them. Without an act of the General Assembly facilitating enforcement, anyone (including the HOA) trying to impose the covenants against anyone else, likely must pursue several months or years of litigation with an uncertain outcome. Years ago, the General Assembly adopted the Property Owners Association Act and the Virginia Condominium Act. This legislation loosens the common law policies against restrictive covenants and provides procedures and powers that make it easier for a statute-qualifying association to collect assessments and enforce restrictions. For this reason, anyone that wants rules for the subdivision to be enforced without prohibitive cost, needs to confirm that the declaration qualifies for the POAA.

Whether the POAA applies matters in reality and is not a merely academic question or legal technicality. Without recourse to the POAA’s arsenal of remedies, the Association may not be able to impose and record fines through an internal hearing process for architectural violations and may be forced to bring a civil suit instead. The POAA allows HOA boards (where the declaration authorizes) to impose rules not stated in the recorded instruments on the community without amending the declaration. Without use of the POAA’s debt collection remedies, the HOA may abandon efforts to obtain assessments from owners because of fees associated with suing unpaying owners. Many abuses of power that cause consumers to complain about HOAs are enabled by these statutes that abrogate protections afforded to landowners under the common law.

The POAA includes the legal definition for an association or declaration to qualify for the rights and duties it provides. If the POAA doesn’t apply, there may still be a board or committee of some sort, but it will have less power. Without recourse to the POAA, covenants may still be enforceable, just not easily. The POAA “applies to a “Development” subject to a “Declaration.” To qualify under the POAA, the Declaration must contain terms such that the Association possesses both the power to (1) collect a fixed assessment or to make variable assessments and (2) a corresponding duty to maintain the common area. This must be expressly stated in the recorded documents and may not be inferred or implied. This legal test looks to what the recorded instruments say, not how things are actually functioning in the subdivision. For property to qualify as a “common area” under the POAA, it does not necessarily have to be conveyed, leased, or owned by an association. The POAA requires the court to construe how the declaration discusses any common areas.

This may seem like a simple definition that developers can easily fulfill by writing up the documents in accordingly. However, many declarations fail to meet this definition because they may impose on the lot owners the duty to pay assessments but fail to obligate the association to spend them on maintaining the common areas. Many developers may want to limit their maintenance obligations in the community while retaining effective control over the association. By failing to obligate the association to maintain the common areas, a developer may unwittingly put the community outside the POAA. This can be good or bad for a particular lot owner, depending upon how dependent they are on HOA services to enjoy their own lot. It is not always in a lot owner’s best interest for their subdivision to fall outside of regulation by the POAA. The POAA allows for reasonable attorney’s fees to a prevailing party. The lot owner may need to rely upon some other provision of the POAA to make their case. Sometimes, the aggrieved owner is the one who needs to enforce the covenants to vindicate their property rights. For example, if a lot owner needs the HOA to take responsibility for a problem with maintenance or operation of a common area, it may be counterproductive to undercut the boards authority to make repairs.

An “association” cannot unilaterally confer upon itself the POAA’s privileges simply by recording an instrument stating that it has the authority to assess the lot owners for common area maintenance and obligating the association to perform such maintenance. That would require an amendment. At common law, any amendment requires consent of 100% of the owners subject to the covenants. The POAA has its own “default” amendment provisions. Most declarations include amendment provisions that vary from the 100% common law requirement or the POAA’s 2/3 amendment provisions. Consultation with qualified counsel is necessary to determine what requirements apply. Lot owners must be wary about amendments because if the statute of limitations in the POAA for challenge to an amendment applies, the dissenting lot owner would need to file the challenge within one year of the effective date.

Do HOA covenants become unenforceable after lot owners get away with disobeying them for many years? Under Virginia law, the right to enforce a restrictive covenant may be lost by waiver, abandonment or acquiescence in violations. The party relying on such waiver must show that the previous conduct or violations had affected the architectural scheme and general landscaping of the area to render the enforcement of the restriction of no substantial value to the property owners. This legal standard sets a high bar for asserting such a defense.

In Virginia, there are procedural requirements for sellers to disclose a host of materials to buyers, including the governing documents of any association to which the POAA applies. The seller does this by paying a fee to the association to send the buyer the materials. Then, the buyer has three days to review these materials and exercise a right to cancel the sale if they are not acceptable. However, the current disclosure system does not adequately protect buyers. Three days is insufficient for a buyer to obtain counsel to review and answer questions about the covenants. If there is something deficient about the disclosure process or dissatisfactory about the covenants, the buyer’s only remedy is to cancel the deal timely. Few purchasers ever do this. The practical effect of this disclosure packet system is to protect sellers and associations from subsequent claims of surprise by purchasers. For insurance purposes, the title company will provide the purchaser with a list of covenants, easements and other encumbrances on the title of the land. Few buyers pay attention to this information.

Virginia law requires associations to register with the Virginia Common Interest Community Board. These registration requirements obligate HOAs and Condominiums to submit annual reports of basic information about the association each year. However, a declaration of covenants may still be enforceable against a lot owner even if the association leadership fails to keep their registration current. Also, HOAs incorporated under the Virginia Nonstock Corporation Act must make submissions and pay fees to the State Corporation Commission each year to keep the corporate status from being cancelled. However, even if a HOA is listed as “automatically terminated” in its official corporate status, this is unlikely to nullify terms of the governing documents. Lot owners should consult with qualified counsel before disregarding HOA notices because they haven’t observed registration formalities with the government.

If covenants and easements pop up in the exceptions to a purchaser’s title insurance, it’s likely that lots in the subdivision are encumbered. This is not always a bad thing, when someone needs to be held responsible for maintaining roads and drains. Some people like the amenities that their HOA offers and want the restrictions to be vigorously enforced so that they don’t have to suffer what they consider eyesores. Other landowners are uncomfortable about paying assessments to a HOA who inadequately maintains the common areas and roads and enforces the covenants in an uneven and erratic fashion. Determining whether the subdivision and its association fall within the scope of the POAA, is essential for evaluating whether certain provisions are practically enforceable. Everyone wants peace of mind and a sense of certainty about what debts they are obligated to pay and what they can or cannot do on their land. Determining whether the association enjoys the powers and duties found in the POAA is the first step to achieving that peace of mind or taking the next step to vindicate their rights.

Selected Legal Authorities:

White v. Boundary Ass’n, Inc., 271 Va. 50 (2006)

Scott v. Walker, 274 Va. 209 (2007)

Anderson v. Lake Arrowhead Civic Ass’n, 253 Va. 264 (1997)

Dogwood Valley Citizens Ass’n v. Winkelman, 267 Va. 7 (2004)

Dogwood Valley Citizens Ass’n, Inc. v. Shifflett, 275 Va. 197 (2008)

Shepherd v. Conde, 293 Va. 274 (2017)

Village Gate Homeowners Ass’n v. Hales, 219 Va. 321 (1978)

Property Owners’ Association Act, Va. Code §§ 55.1-1800 through 55.1-1836

photo credit: Editor B Surreal Suburban Subdivision via photopin (license)

May 24, 2019

Injunctions in HOA Cases

Some people like to talk about awards of money damages or attorneys’ fees that the courts order losing parties to pay. Litigation involving landowners, HOA or condominium boards revolve around what remedies the court may apply if it sees things the same way as one of the parties. Contrary to the focus of many news articles, monetary awards may not be the essential remedy available in property rights or corporate governance cases. In Virginia, and elsewhere, the law makes awards of money damages or possession of property preferred remedies. However, in many cases, an award merely of money damages is insufficient to properly vindicate the rights of an aggrieved party. In disputes between owners and HOA boards or neighbors involving the use of land, claimants frequently ask for the court to order the defendant to do certain things or to stop performing improper actions. This is called an “injunction.” For example, a neighbor or the HOA may be causing a nuisance on a lot or common area (e.g., improperly diverting drainage water), that unreasonably damages or interferes with the adjoining landowner’s rights. There are other examples which do not involve nuisances. An aggrieved owner could just sue for money, but the offending party may continue with the wrongful behavior, which results in more damage or interference justifying another suit. A succession of suits for money damages doesn’t solve the root of the problem. Community associations and their members have ongoing relationships that usually only end if someone sells their property or dies. While courts apply high standards for aggrieved parties to obtain injunctive relief, the scope of subject-matter to which injunctions may apply is as broad as the topics addressed in the governing documents, the applicable statutes or other controlling legal principles, such as the doctrine of nuisance. Cases where structural failure may cause catastrophic injury to person or property absent corrective action often include requests for injunctive relief. The ongoing character of neighborhood disputes makes an injunction a powerful remedy. The purpose of this blog post is to summarize how injunctive relief may work in HOA, condominium or adjoining landowner disputes.

Community associations revolve around a declaration of covenants, and any amendments, that function as a “contract” between the association board, committees, the developer and the lot or unit owners. To interpret and enforce this “contract”, Virginia courts apply statutes and judge-made doctrines pertaining to restrictive covenants, easements and deeds. Under the judicial doctrines, if a party requests a court to enter an injunction against conduct that violates a covenant, they must show that the covenant is not ambiguous or presents other enforcement problems. Courts traditionally apply heightened skepticism towards enforcement of covenants and easements. This is why lobbyists asked the General Assembly to enact the Property Owners Association Act (POAA) and the Virginia Condominium Act (Condo Act) and their amendments. This legislation made it easier for association boards to enforce HOA covenants and powers. The POAA and Condo Act provide for injunctions (not excluding money damages or other relief) as a remedy available to lot or unit owners for breach of the association covenants by the board or an adjoining owner. If those statutes don’t apply, a claimant must go to the Circuit Court to obtain an injunction. The association statutes provide an exception, allowing HOAs, condominium boards or owners to go to the local Circuit Court or the General District Court for money damages or injunctions for violation of the declaration of covenants.

In Virginia state courts, to obtain an injunction, the complainant must show irreparable harm and lack of an adequate remedy at law. The Supreme Court of Virginia has held that when an injunction is sought to enforce a real property right, a continuing trespass may be enjoined even though each individual act of trespass is in itself trivial, or the damage is trifling, nominal or insubstantial, and despite the fact that no single trespass causes irreparable injury. The injury is deemed irreparable and the owner is protected in the enjoyment of his property whether such be sentimental or pecuniary. An injunctive order must be specific in its terms, and it must define the exact extent of its operation so that there may be compliance. The declaration of covenants, like other contracts, require parties to perform as prescribed. The entry of an order granting a motion for an injunction based on HOA or condominium covenants takes this a step further, because disobedience to a court order allows the aggrieved party to file a subsequent request with the court to hold the party bound by the injunction to be held in contempt. This is why attorneys seek to avoid having their clients become subject to injunction orders.

There are two main kinds of injunctive relief. One is a “permanent injunction” which the judge enters at the end of the case should she agree that such a remedy is proper in a final order. The other kind is a “preliminary” or “temporary” injunction which the court may enter on motion for the time between when the suit is filed and the trial. Preliminary injunctions provide immediate relief, subject to revision at the end of the case. In Virginia, different judges apply different legal standards for preliminary injunctions. Many draw from common law cases which do not articulate a uniform standard. Some judges apply the strict federal standard for preliminary injunctions, requiring a showing that (1) the plaintiff is likely to succeed on the merits, (2) the plaintiff is likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, (3) the balance of equities tips in his favor, and (4) an injunction is in the public interest. Preliminary injunction orders are unusual because waiting until the case is decided on the merits affords more due process to the defendant.

Association boards can sue for injunctions, but they don’t have to. The POAA and the Condo Act allow associations to fine property owners for violating covenants or rules when the declaration allows fines and the board strictly fulfills the requirements of the declaration and the statute. I don’t agree with these fine statutes because they enable HOAs to get a free pass from having to plead and prove breach of the covenants or the appropriateness of an injunction enforceable by contempt. In a sense, HOAs and condominiums are able to skip over months of litigation “due process” to determine if a remedy is proper for breach of the governing documents and instead, just enact a kind of contempt penalty. Owners don’t have the ability to jump ahead of the process and fine people without having to litigate for a year or more. Nonetheless, preliminary and permanent injunctive relief are powerful weapons for owners aggrieved by the wrongful actions of association boards or adjoining owners. Owners can draw from the governing documents, statutes and common law doctrines to achieve a judicial remedy or favorable settlement that resolves the dispute without forcing the owner to sell or engage in endless lawfare. Understanding what court remedies may be available, such as money damages, attorneys’ fees or injunctions is necessary in order to chart a legal strategy to resolve the dispute and achieve peace of mind.

2022 Update:

In 2022 I posted a new article, “Homeowner Injunction Claims Against HOAs.” This new article contains additional information regarding this important topic.

Selected Legal Authority:

Scott v. Walker, 274 Va. 209 (2007)

Va. Code § 55-515 (POAA – Compliance with declaration)

Va. Code § 55-513 (POAA – Adoption and enforcement of rules)

Farran v. Olde Belhaven Towne Owners’ Ass’n, 83 Va. Cir. 286 (Fairfax 2011)

Unit Owners Ass’n of Buildamerica-1 v. Gillman, 223 Va. 752 (1982).

Winter v. N.R.D.C., Inc., 555 U.S. 7 (2008)

Levisa Coal Co. v. Consolidation Coal Co., 276 Va. 44 (2008)

March 27, 2019

Rain, Rain, Go Away: Drainage Problems in the HOA

Drainage disputes among adjoining property owners are common anywhere developers subdivide and build on land. Raw land’s natural grading channels surface water into streams and rivers. Development plans frequently ignore potential drainage problems and construction disturbs drainage patterns, often causing water to divert or accumulate. When buildings and hardscapes replace trees and grass, soil cannot absorb water. Instead, the grading of the road, sidewalk, eaves or gutters channel water. All rainwater has to go somewhere. Unless a house or other building is on the top of a hill, a property owner may suffer from surface water diverted from adjoining parcels.

State common law governs the rights and responsibilities of adjoining property owners regarding surface water diversion. In residential neighborhoods, HOA roads, greenspace and other common areas encompass owners’ lots. Many lots lie at lower elevations from neighbors or common areas. Even if a developer constructs the subdivision according to an acceptable drainage design, all it takes is one neighbor or HOA board that improperly maintains or modifies drainage features to cause nuisances at lower-lying homes.

In Virginia and elsewhere, adjoining property owners are not strictly liable for damage or interference caused by changes they make to drainage conditions on their own property. Courts apply a reasonableness standard, but the burden is on the aggrieved neighbor to prove that the diversion of water is improper. The Supreme Court of Virginia’s judicial precedents provide guidance as to whether damaging changes to grading conditions on an adjoining property subject that owner to liability.

One leading Virginia case is Kurpiel v. Hicks. In 2011, Patricia and George Kurpiel of Stafford County sued their adjoining neighbors, Tammy and Andrew Hicks. The Kurpiels alleged that the Hicks stripped their land of vegetation, changed the elevation of their land, brought in additional fill dirt and caused stormwater, sediment and siltation to flow onto the Kurpiel lot. The Kurpiels sued the Hicks for trespass, requesting the Circuit Court to enter an injunction against the flooding.

Under Virginia’s common law, the courts view surface water as a “common enemy.” By general rule, owners may “fight off” surface water by construction or changing drainage conditions to their own property, even if this discharges additional water onto an adjoining parcel. This recognizes the higher landowners’ freedom to make changes to their land, within reason. The focus of this blog post are the exceptions to the common enemy doctrine, and how such exceptions may be tools to adjoining owners.

Unreasonableness:

The “common enemy” doctrine’s main exception provides that diversion of surface waters may not be done wantonly, unnecessarily, or carelessly, must not injure the rights of another, and must be a reasonable use of the land exercised in good faith. Whether any exception applies will depend upon each case’s unique facts. Many cases require the testimony of an engineer or another expert to professionally evaluate the sufficiency of drainage. Because the exception to the “common enemy” doctrine is fact specific, the reasonableness of the adjoining owner’s changes present a factual question to be decided at trial.

To sue an adjoining owner for flooding, the aggrieved party must choose one or more claims or “causes of action.” The “common enemy” doctrine applies regardless to whether the lawsuit is for trespass, nuisance or negligence. The adjoining owner may also be able to sue for violation of restrictive covenants recorded in the land records. The Kurpiels only sued for trespass, which provides that every owner is entitled to the exclusive and peaceful enjoyment of their own land, and redress if such enjoyment shall be wrongfully interrupted by another.

The Circuit Court of Stafford County dismissed the Kurpiels’ lawsuit on the grounds that it failed to allege sufficient facts to establish the “reasonableness” exception. The Supreme Court of Virginia reversed the decision, finding that the Circuit Court improperly short circuited the case, finding reasonableness of surface water diversion to be a factual issue for trial.

No Artificial Channels:

“Unreasonableness” is not the only exception available to flooded neighbors. The Supreme Court of Virginia held in other cases that a landowner cannot collect water into an artificial channel or volume and pour it upon the land of another to his injury. As one example, an owner cannot drain surface water into a ditch or pipe and aim that artificial channel onto an adjoining property.

Eaves of Buildings:

Sometimes disputed stormwater is from the eaves or gutters of a building. The water that drips from the eaves or downspouts of a building is not treated as “surface water” per the “common enemy” doctrine. Stormwater from a roof or downspout is another exception. There is no natural right of drainage from the roof of a building. This is consistent with the other exception, because gutters and downspouts are “artificial channels.”

Disturbing Existing Watercourses:

An additional exception is where the flow of water is in a defined channel or watercourse. In that instance, a landowner may not injure another by interfering with its natural flow.

HOA Covenants:

The afore described rule and exceptions define the obligations that adjoining property owners have to one another that arise where there are no covenants of record regarding nuisances and drainage. Most residential subdivisions have restrictive covenants, and many establish HOAs. Those covenants may include provisions regarding nuisances or other restrictions on how an owner may divert water. Those covenants will define the HOA’s rights and obligations to maintain common areas and rights of way. Some covenants contain provisions inserted in attempts to limit the liability of the homeowners association for property damage from stormwater problems. If the flooding comes from an adjoining lot or an HOA common area or road, the aggrieved lot owner needs copies of the declaration of covenants and any amendments to determine how they may add or subtract from the adjoining owners’ rights and responsibilities in dealing with the “common enemy.”

Courts do not apply local government-type legal standards in evaluating HOA actions. Also, courts do not interpret restrictive covenants encumbering real estate according to the general rules regarding garden-variety contracts. There are a few basic principles to consider when interpreting HOA covenants:

- Courts treat HOA covenants like “contracts” to which each party owning land in the subdivision are party, including the lot owners, the HOA, possibly the declarant and/or holders of easement rights such as utility companies.

- Courts interpret covenants according to conditions existing at the time the developer recorded the document. HOAs or lot owners commonly change grading and drainage on their lots to fend off the accumulation of rainwater in the cheapest means possible.

- The courts treat interpretation of what HOA covenants mean as “matters of law” discernable on motion or appeal without taking evidence. Applying them to disputable facts requires evidence at trial.

- The courts interpret covenants “as a whole,” resisting the tendencies of trial lawyers to quote language out-of-context.

- The courts enforce restrictive covenants where the intentions are clear and the restrictions are reasonable.

- While ambiguous covenants may be a challenge to enforce, courts may find that a party has a right that may not be explicit but is plainly implied by the language.

- Covenants are construed strictly against persons seeking to enforce them, and substantial doubt or ambiguity is resolved in favor of free use and against restrictions.

HOA directors frequently misunderstand their rights and duties. Many falsely believe that once the members elect the board of directors, they enjoy unfettered exercise of business judgment. Some believe that a lot owner can’t challenge decisions outside of the next election. Many HOA boards believe that when they award a contract to maintain or renovate a road or drainage system to the lowest bidder, lot owners can’t complain. This is not true. The HOA must fulfill the requirements imposed upon it by the declaration. The HOA, as a fiduciary, cannot show favoritism towards certain owners over others, and divert flooding away from one lot onto another lot. The HOA is liable in contract for failure to fulfill obligations clearly established by the declaration.

Under Virginia law, the fundamental purpose of a property owners association is to collect assessments from lot owners and spend those receivables on maintaining the common areas, such as roads, greenspace and drainage improvements. The Supreme Court of Virginia has held that if the declaration fails to require this, the governing body established by the covenants may not qualify for the various remedies and powers established by the Property Owners Association Act. This rule is consistent with federal law requiring community or public purpose for the spending of HOA assessments to preserve tax exempt status. It is often difficult for a HOA board evade its duties to maintain the common areas it owns.

If an HOA or adjoining neighbor makes changes to their property that causes a flood, the damaged landowner has rights. When the stormwater diversion is harmful, usually there is at least one legal theory by which the adjoining owner or HOA may be held accountable. Flooding of houses, yards and driveways is a nuisance that no landowner should have to live with.

Selected Legal Authorities:

Kurpiel v. Hicks, 284 Va. 347 (2012)(rule of reasonableness)

Third Buckingham Community, Inc. v. Anderson, 178 Va. 478 (1941)(channels)

Noltemeier v. Higginbotham, 32 Va. Cir. 388 (Spotsylvania Co. 1994)

Raleigh C. Minor, The Law of Real Property (1908)

Scott v. Walker, 274 Va. 209 (2007)(how to read covenants)

photo credit: r.nial.bradshaw 160404-neighborhood-sidewalk-morning-clouds.jpg via photopin (license)

February 6, 2019

Rental Restrictions in Virginia Condominiums

Teachers often compare property rights to a “bundle of sticks.” Each stick represents a discernable owner’s right such as the right to occupy, the right to use the community swimming pool, the right to live free of water intrusion, the right of access, and so on. One powerful right is the ability to rent out possession of the property. A property that cannot be conveniently rented is less useful, and therefore, less valuable.

Neighbors often view renters in a negative light. They view a community predominantly composed of owner-occupants as more vibrant than that of a community full of renters. Many view owner-occupants as wealthier, more committed to maintaining their property and more engaged in the community. Individual owners may desire the privilege of renting their own property while at the same time wanting their neighbors to be owner-occupants.

This conundrum readily manifests itself in condominium developments. High-rise condominium complexes often look and feel like rental buildings. Some investors shop for condominium units because they make great rental units during a housing shortage. However, condominium developers and managers frequently insert rental restrictions into covenants, bylaws or board-adopted regulations. While buyers and owners want the sale of their units to qualify for FHA-sponsored financing, current mortgage market conditions place pressure on the resale values for condominium units and the FHA imposes owner–occupant ratio threshold requirements for certain types of desirable financing options. For example, if the current applicable threshold is 51% owner-occupants, the current owners, as a group, will want to suppress rentals in the building to protect the resale value of their units. At the same time, those owners will individually have a personal interest in the option to rent their units if so desired. Therefore, rental restrictions in condominium governing documents are breeding grounds for conflict.

Many perceive short-term rentals as a threat to condominium communities since most condominiums are not set up to be operated as hotels or resorts. For example, a condominium concierge is not the same as a hotel receptionist, the amenities in a residential condominium differ from those found at a resort, and parking passes are often in short supply. In addition, short-term renters have a reputation for treating condominium units like hotel rooms, adding noise and traffic. To that end, it’s common for covenants or regulations of a condominium to contain provisions forbidding, discouraging or restricting the rights of owners to list and operate their units using Airbnb, HomeAway or other short-term rental websites.

Here we will discuss rental restrictions in Virginia condominiums. Every condominium association has different rental restrictions. In addition, the city or county may have separate rules (ordinances) of its own regulating short term rentals, which a short-term rental landlord must be aware of. This article focuses on where to look to find the applicable association rules and how to determine their enforceability. Frequently, rental restrictions cannot be enforced as clearly and certainly as management argues. For that reason, condominium unit owners owe it to themselves to fully understand the meaning and possible enforceability of the rental restriction rules they are bound by.

In condominium matters, one starts with the careful review of the declaration of covenants and bylaws. The condominium association is charged with administering the declaration of covenants. The Supreme Court of Virginia held that a condominium declaration is in the nature of a contract between the condominium association and the unit owners (including the unit owners among each other). One must look to Virginia law to determine how to interpret the declaration and what remedies may be available. The declaration and plats define the shape of the property rights that the owner can pass on to the tenant in a lease. The owner cannot convey rights to a tenant that the owner does not enjoy under the governing documents. Owners commonly incorporate the condominium instruments into the lease by reference to avoid situations where the tenant insists that they have a right to do something which the covenants do not allow.

The principal authority for interpreting covenants is the Virginia Condominium Act. Between 2015 and 2016, the General Assembly added provisions limiting the authority of a condominium association to restrict the rental of units. Va. Code § 55-79.87:1(A) provides a broad list of restrictions that a condominium board cannot impose unless provided for in the declaration or bylaws. Even if the amendments weren’t adopted, the Supreme Court of Virginia has held that a condominium association cannot do anything that isn’t explicitly or implicitly authorized in the governing documents. The legislature adopted this legislation during the emergence of short-term rentals. Let’s take a look at these restrictions that are permitted only if expressed in the governing documents or other parts of the Condominium Act:

- Condition or prohibit the rental of a unit to a tenant by a unit owner or make an assessment or impose a charge (except as otherwise provided by the statute). This seems helpfully broad to a unit owner challenging a board-adopted restriction.

- Charge a rental fee, application fee or other processing fee in excess of $50.00.

- Charge an annual or monthly rental fee.

- Require the unit owner to use a lease or addendum form prepared by the association.

- Charge any deposit from the unit owner or the tenant.

- Have the authority to evict the tenant or require the owner to delegate eviction power to the association. Buyers ought to be disturbed by provisions in condominium documents giving condominiums such authority.

Va. Code § 55-79.87:1(B) authorizes the association to require the unit owners to provide the names and contact information of tenants. Without such information, the association’s practical ability to enforce any rental restrictions in the covenants is limited. The authority to mandate registration is necessary to effectively regulate. This amendment made it easier to sort out what restrictions may be enforced without a deep dive into the case law.

Where the terms of restrictive covenants are clear and unambiguous, the duty of the court is to interpret them in accordance with their plain meaning. The association’s board or committee may not act in contravention of its governing documents. Unfortunately, many association governing documents are unclear, ambiguous or uncertain in meaning or effect, such that experienced judges, lawyers or professors may favor conflicting interpretations.

Attempts to use recorded covenants to restrict rental rights predates the rise of short-term rental websites. In Scott v. Walker, the Supreme Court of Virginia considered case precedents in deciding whether an HOA covenant requiring real property be used only for “residential purposes” would prohibit short term rental of a single-family dwelling. The Supreme Court of Virginia found the covenant ambiguous and for that reason construed it in favor of free use of land.

William Scott and Suzanna Scott owned a lot in the Harbor Village HOA on Smith Mountain Lake. Their lot was located near Roanoke. After purchase, the Scotts began to use their property as a short-term rental. Donald and Charlotte Walker, their neighbors, were unhappy about the Scotts’ short-term renting. They sued the Scotts. The Circuit Court of Bedford County found that rental on a nightly or weekly basis is not “residential” because the property is not being used as a domicile. Understanding the Circuit Court’s view is not difficult. A hotel or bed and breakfast is a business, not a collection of homes. If a hotel guest doesn’t pay, then the hotel probably won’t need to file an eviction lawsuit.

The Supreme Court of Virginia construed the covenant according to the plain meaning rule and the rule that errs on the side of free use when there is doubt or ambiguity.

It is . . . the general rule that while courts of equity will enforce restrictive covenants where the intention of the parties is clear, and the restrictions are reasonable, they are not favored, and the burden is on him who would enforce such covenants to establish that the activity objected to is within their terms. They are to be construed most strictly against the grantor and persons seeking to enforce them, and substantial doubt or ambiguity is to be resolved in favor of the free use of property and against restrictions.

Scott v. Walker, 274 Va. 209 (2007).

Given the limitations imposed by the Condominium Act and the series of decisions by the Supreme Court of Virginia, condominium unit owners owe it to themselves to not take their board or manager’s word for it when they waive a board-enacted “Policy Resolution” regarding the rental of units. The rules may not be enforceable or may not be enforceable in the manner that the board of directors wants. The right to rent out a condominium unit may determine whether the owner can keep the property. The Supreme Court of Virginia’s method of interpreting ambiguous covenants in favor of free use is something that any attorney dealing with rental restrictions in Virginia condominiums must fully understand.

Discussed Authorities:

Sully Station II Community Ass’n v. Dye, 259 Va. 282 (2000).

Va. Code § 55-79.87:1 (Condominium Act – Rental of Units).

Scott v. Walker, 274 Va. 209 (2007).

photo credit: sjrankin Unsettled Weather via photopin (license)

September 21, 2017

Standing to Sue While Sitting on the Board

Standing is a party’s right to make a legal claim in Court. When the judge comes out to sit on the bench, she will read the cases and the parties or their attorneys come forward as called. “Standing” is the right to seek a legal remedy as shown by the facts alleged. Judges ordinarily decide questions of standing without ruling on the merits of the case. That said, a party dismissed for lack of standing cannot win. Standing just means that the case can proceed.

“Standing” has been in the news lately. There was a federal court complaint filed a monkey, Naruto, who in 2011 took a selfie with a camera and later sued David Slater, the owner of the camera for copyright infringement. The monkey and photographer litigated over whether the nonhuman primate has standing to sue under the U.S. Copyright Act. The notoriety of the suit increased the popularity of the photograph, raising the stakes in the case. The case settled this month, so we may never know whether a monkey can have standing. (I am doubtful because monkeys do not have upright posture. They walk on their feet and the knuckles of their hands and do not “stand” like we do.) In most cases, the question of standing is not controversial. If someone is party to a contract, they ordinarily have standing to sue under that contract. If someone runs into my mailbox with their car, I have standing against them because they damaged my property.

The question is not always so clear. For example, in community associations, the declaration of covenants defines legal relationships among the board and owners. If an owner feels that that their rights have been infringed by the actions of others in their community, who do they have standing to sue? There are numerous possibilities:

- The HOA as a corporate entity

- Individual officers or directors

- An architectural review committee

- Individual neighbors

- Local land use officials

- The developer or declarant

This is relevant to whether the owner actually has a case. Because of filing deadlines, expenses and headaches, owners need to avoid “going ape” on the wrong party. If the HOA is not an issue, then the owner would have to look at another theory such as trespass, nuisance, negligence or other type of right that may exist outside of community associations law. When the dispute involves a right or duty imposed by the governing documents of an HOA or powers of the board, then the answer will be found in interpretation of the covenants and other governing documents. The answer may not be apparent from the four corners of the HOA covenants. Owners have rights, duties and potential remedies that exist under statute or common law that may be implied by, but not specifically referenced in, the association documents.

The Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia considered the doctrine of standing in HOA matters earlier this year. Wilfred Welsh owned a townhouse in Washington, D.C. He was a Director and Secretary of the Chaplin Woods Homeowners Association. Welsh was unhappy because Beverly McNeil and Alvin Elliott rented their townhouse to Oxford House. Oxford House organized a small group home for women recovering from alcoholism and substance abuse. Welsh pointed to the fact that persons living in this townhouse were not party to the Oxford House lease. Welsh contended that the Oxford House lease was not approved by the board. A board majority did not share his views so he filed a lawsuit against McNeil and Elliot in his own name. Welsh did not name Chaplin Woods as a party. Chaplin Woods made no effort to formally intervene in the case.

McNeil and Elliot filed a counterclaim against Welsh, asserting that he violated the Fair Housing Act and the D.C. Human Rights Act by his opposition to their request for an accommodation for their tenants. They said that as Secretary, he delayed and obstructed their request for an accommodation by not transmitting Oxford House’s letter to the HOA’s attorney. Welsh insisted that he had standing to sue McNeil and Elliot because the Bylaws granted individual members the same rights as the Association to enforce the governing documents. After he filed suit, the board formally approved the lease agreement to Oxford House. Welsh argued that McNeil and Elliot could not sue him for Fair Housing because he was just a single board member with no power to exercise the HOA’s corporate powers on his own. So Welsh v. McNeil had two juicy HOA law issues: (1) Can an owner individually enforce governing documents after the board waived the right to enforce? and (2) Can a rogue director or officer be sued individually under housing discrimination laws for obstructing a request for a reasonable accommodation for a disability?

For a few years, Oxford House functioned with leases with the owners that were not approved by the Board. Apparently, the occupants simply lived in the townhouse without board action to approve the leases or kick them out. When pressed on this issue, Oxford House formally requested a reasonable accommodation under fair housing laws. Oxford House sought permission for the women to live in the house, which would facilitate their recovery from substance abuse challenges without having their individual names on lease agreements approved by the board. Oxford House wanted the board to approve a lease in its corporate name. The lawyers for the HOA and Oxford House went back and forth on this.

Before the board decided, Mr. Welsh filed a complaint in his own name against McNeil and Elliot. He wanted the Court force them to stop leasing their property in a manner not contemplated by the bylaws. The rules required the leases to be in the names of the occupants. Welsh’s suit was not sanctioned by the board. After the suit was filed, the board met and decided to approve the disability accommodation request. Welsh apparently attended this meeting but did not vote, citing a conflict of interest caused by his pending suit. The President sent McNeil & Elliot a letter saying that the HOA approved the lease. The board did not subsequently walk back on this approval. This threw a “monkey wrench” of sorts into Welsh’s case. Was Welsh’s claim rendered moot by the board’s formal decision to waive the community’s rights to enforce the bylaw?

Both sides moved to dismiss each other’s claims as lacking standing to sue. The judge agreed with both and dismissed both claims. He found that because the board approved the lease, there no longer was a dispute to be litigated. He observed that Welsh did not sue the HOA so he had no way of disputing the board’s decision without suing them directly.

Welsh did have standing to sue when he filed his complaint. An HOA has the primary responsibility for enforcing its covenants, rules and regulations. However, an individual owner also has standing to enforce the governing documents unless they provide otherwise. If the HOA simply takes no action, then ordinarily an owner may bring his own action. The question in Welsh v. McNeil was what happens to the owner’s cause of action if the board “preempts” it by deciding one way or the other? The Court of Appeals interpreted the Bylaws to mean that once the board acted to approve the lease, an individual like Welsh was thereafter deprived of his claim: “Generally speaking, a homeowner’s association has the power to release or compromise any claim it has the right to assert, and to do so over the objection of individual homeowners, who then are bound by the association’s resolution of the claim.” The D.C. Court of Appeals cited the 1985 decision Frantz v. CBI Fairmac Corp., where the Supreme Court of Virginia observed that where a condominium association has the authority to bring a claim against a violation of a common right, it also has the power to compromise that claim and that the individual unit owners would be bound by that compromise.

The D.C. Court of Appeals observed that it would not make sense to give individual owners the power to “override” decisions of the board of directors when it comes to matters of community interest. The Court was careful to recognize that one must distinguish between matters of community concerns and individual property rights. For example, if one owner rents out their property in a manner that violates the rules or fails to abide by architectural appearance rules, then this is something that an individual owner could not legally enforce once the board took it up. On the other hand, the board has no authority to unilaterally compromise the claim of an individual owner against the board itself or another owner.

If an owner’s interests in a claim for enforcement against another owner is no different than any other owner, then it is probably one of common concern that the board can “foreclose” or “preempt” by pursuing, waiving or settling. On the other hand, if the owner’s own property rights were damaged, infringed or invaded, then it may not be something that the board can take away.

Wilfred Welsh did not contend that he was asserting any right other than the same right the association possessed to enforce against McNeil and Elliot for the common interests of the community. This makes sense because Welsh’s interests were not affected by having fellow residents whose names were not written on any deed or lease any differently than any other townhouse owner.

If Welsh was unhappy with the way that the board decided to compromise the claim for himself and everyone, he would not be completely without options. Welsh could have tried to sue the association directly for breaching their contractual duties to him by deciding the issue about the Oxford House as they did. But he did not.

Welsh argued that the HOA’s decision did not moot his claim because the board did not properly approve the lease. He contended that the board did not actually obtain the requisite number of votes to approve the lease. The Court of Appeals decided that whether they did or not, the President sent a letter to McNeil and Elliot did, and the board never retracted that letter. McNeil and Elliot had a right to rely upon the President’s letter.

Many people are attracted to involving themselves in HOA boards and committees because they believe enforcement of the rules will prevent the “wrong” types of people from moving into their community. Many may fear recovering alcoholics or drug addicts living on their street. For many people HOAs seem to carry an aura of exclusivity that they find very attractive. I don’t like these attitudes – what if my neighbors were to decide that they consider me to not be the kind of person they want living near them? HOAs tend to weaken individual property rights and strengthen the notion that someone else can do a better job of deciding how an owner should use their own property. I also believe that societal problems like substance abuse are too complex to be solved by NIMBY initiatives.

This case would have unfolded very differently if a majority on the board agreed with Welsh. That is certainly not unheard of. Housing discrimination cases against HOAs and condo boards are common. The board could have denied the accommodation request outright, attempted to enforce the leasing rules, or allowed Welsh to proceed on his own without ruling one way or the other.

Some of my readers may be wondering how it can be fair for the board to take away rights provided to owners by the governing documents by waiving or settling the violation. Bear in mind that an average homeowner in a HOA does not want every other member of the association to have the authority to sue for alleged violation of the governing documents. It is in the interest of owners to narrow the number of parties who can assert legal claims against them.

The other issue raised in this case is whether a director or officer, acting on his own without the support of a majority of the board can engage in conduct opening himself up to liability under housing discrimination laws. The residents of Oxford House could be found to be disabled persons entitled to accommodation because they seek treatment for drug and alcohol abuse. The D.C. Superior Court ruled that Welsh could not suffer personal liability because as a single board member he could not bind the association. The question was rendered moot because the board ultimately approved the Oxford House lease. However, Welsh did not argue that it was moot because he contended that the approval of the lease was not valid and binding. The Court of Appeals reversed, finding that the fair housing claims against Welsh could proceed. While Welsh had no power to ultimately decide the accommodation requests on his own, as corporate secretary he had an ability to delay board decisions by holding onto written requests and not forwarding them on to the board’s attorney or other representatives. McNeil and Elliot alleged that Welsh substantially contributed to delays to approval of the accommodation. The Court of Appeals observed that delays like this, which go on for considerable lengths of time with no apparent end in sight have the effect of an outright denial. While McNeil and Elliot may not ultimately prevail on their fair housing claim against Welsh, the Court of Appeals ruled that it may proceed through the courts.

In any dispute involving property associations, an owner who has suffered damage or invasion of property rights must carefully consider the party against whom she may have a legal claim. She must also consider whether the association or other owners also have a claim, and whether the association can compromise or waive such claims for everyone. For many owners, it may not make sense to pursue claims against neighbors for the kinds of claims that the board can come along and make moot by a decision at a meeting. Claims like technical violations of architectural conformity standards may not make sense to bring because the commitment required to pursue such legal action might not result in any money or rights upon the claimant. Understanding the difference between “private” claims between owners and “common” claims is important to bringing or defending any case among individual owners in a community association. Qualified legal counsel can help to sort through and interpret the governing documents to provide critical insight into the nature of a claim by an owner, neighbor or association.

Case Citations:

Welsh v. McNeil, 162 A.3d 135 (D.C. 2017)

Frantz v. CBI Fairmac Corp., 331 229 Va. 444 (1985).

photo credit: A. Nothstine LeDroit Park Rowhouses via photopin (license) (Does not depict any property described in article, to my knowledge)

July 28, 2017

Freedom of Speech is a Hot Topic in Community Associations

Freedom of speech is a hot topic in community associations. Some of these First Amendment disputes concern the freedom of a property owner to display flags, signs or symbols on their property in the face of board opposition. Conflict between association leadership and members over free speech also spreads into cyberspace. One such case recently made its way up to Florida’s Fifth District Court of Appeals. On July 21, 2017, the appellate judges reversed part of the trial court’s ruling in favor of the association. Howard Adam Fox had a bad relationship with certain directors, managers and other residents of The Hamptons at MetroWest Condominium Association. Several lessons here for anyone who communicates about associations on the internet.

The July 21, 2017 appeals opinion does not describe the social media communications and blog posts that gave rise to the dispute. I imagine that they consisted of personal attacks that may have been alleged to contain slanderous material. The details are left out of the opinion, probably with a sensitivity towards the persons discussed by Mr. Fox online. In general, I do not like the spreading of false, slanderous statements in personal online attacks. To the extent that Fox had legitimate grievances about goings on at the Hamptons at MetroWest, the character of his criticisms seems to have eclipsed any merit. There are usually better ways of solving problems than angrily venting them in online forums.

The board filed a complaint seeking a court order prohibiting Mr. Fox from, “engaging in a continuous course of conduct designed and carried out for purposes of harassing, intimidating, and threatening other residents, the Association, and its representatives.” The association alleged Mr. Fox violated the governing documents of the condominium by his blog posts and social media activity. The court granted an ex parte injunction prohibiting the alleged wrongful conduct. This means that the judge initially considering the case did not wait for Mr. Fox to make a response to the lawsuit. Later, Mr. Fox and the board reached a written settlement wherein Fox agreed to cease certain activities. The final order in the court case incorporated the terms of the settlement. Making terms of the settlement a part of the final order means that the association does not have to start its lawsuit all over again to enforce the deal. They just need to bring a motion for contempt if Fox violates the order. Howard Fox represented himself and did not have an attorney in the trial court and appellate litigation.

Soon thereafter, the association filed a motion for contempt, alleging that Fox violated the settlement and final order. In the contempt proceeding, the trial court went further than simply enforcing the terms of the settlement. The judge forbade Fox from posting or circulating anything online about any residents, directors, managers, employees, contractors or anyone else at the Hamptons. The judge required him to take down all current posts. If someone asked him on social media about his community, and he wanted to respond, he would have to call them on the telephone.

Fox appealed this contempt order on the grounds that it violated his First Amendment rights under the U.S. Constitution. The Fifth District Court of Appeals agreed. The trial court’s ruling was what is called a “prior restraint.” The contempt order did not punish him for past wrongful actions. It looked permanently into his future. Prior restraints against speech are presumptively unconstitutional. Temporary restraining orders and injunctions are “classic examples” of prior restraints.

The appellate court focused on the public nature of the type of speech the lower court order forbade. This makes sense. While an association is private, it is a community nonetheless. There is no real conceptual difference between online communications and other types of speech. Matters of political, religious or public concern do not lose their protected status because the content is insulting, outrageous or emotionally distressing. In a condominium, many matters of community concern could easily be characterized as political, religious or public. Federal, state or local rulemaking may impact the common business within the association. While community associations are “private clubs,” the things that members communicate about are mostly public in the same sense as town or city ward communities. To paraphrase this opinion, “hate speech” is protected by the constitution, unless certain very limited exceptions apply, such as obscenity, defamation, fraud, incitement to violence, true threats, etc.

This Florida appellate court found that the trial court violated Fox’s First Amendment rights when it ordered the “prior restraint” against him making any posting of any kind online related to his community. On appeal, the court preserved the rulings finding contempt for violation of the settlement agreement. So, Fox must still comply with the terms of the settlement. The case will go back down for further proceedings unless there is additional appellate litigation. Nerd-out further on the constitutional law issues in this case by reading the useful Volokh Conspiracy blog post on the Washington Post’s website.

The appeals court did not find that any covenants, bylaws, settlements, or other association agreements violated the First Amendment. This opinion does not mean that people cannot waive their rights in entering a private contractual relationship with each other.

Usually, only “state actors” can be found to violate the Constitution. An association is not a “state actor” because it is not really governmental. Here, the “state actor” in the constitutional violation was the trial-level court and not the association. What difference does it make? Ultimately, the courts, review the validity of board actions, determine property rights and enforce covenants. The association board requested relief that apparently lacked support in the covenants or the settlement agreement. To protect their rights, owners must understand when their board is doing something or asking for relief outside of its contractual authority.

There is one final point that the court opinion and the Volokh Conspiracy blog do not discuss which I want my readers to appreciate. Owners of properties in HOAs do not simply have a right to communicate with each other and the board. They have an obligation. The covenants, bylaws and state statutes provide for the board to be elected by the members. Members can amend governing documents by obtaining a requisite of community support. The non-director membership is supposed to be an essential part of the governance of the association. If the members and directors do not have an effective means to communicate with each other, then the community cannot function properly. Community associations can have thousands of members and residents. The may cover the acreage like that of a town or small city. The internet, in both password protected and public sites provides a convenient way for information and messages to be shared. Limits on an owner’s ability to communicate with her board or other parties to the “contract” prejudices her rights under the governing documents. I do not like covenants or bylaws that limit an owner’s ability to obtain information or communicate concerns within the governance of the association. Donie Vanitzian recently published a column in the LA Times entitled, “Freedom of Speech Doesn’t End Once You Enter a Homeowner Association.” She discusses proposed California legislation to enshrine owners’ rights to assemble and communicate with each other about community concerns. Ms. Vanitzian makes an important point that because speech may be deemed “political” should not justify management suppression. Having rights to participate in the meetings of one’s HOA without the right to talk about what is going on is like owning land deprived of any right of way or easement to the highway. While the new Florida opinion does not discuss this point, it is consistent with the basic values of the First Amendment.

For Further Reading:

Photo Credit:

torbakhopper pictures in the night : san francisco (2014) via photopin (license)(does not depict anything discussed in article)

July 20, 2017

Are Legal Remedies of Owners and HOAs Equitable?

Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy recently wrote in an opinion that, “Property rights are necessary to preserve freedom, for property ownership empowers persons to shape and to plan their own destiny in a world where governments are always eager to do so for them.” Murr v. Wisconsin, 198 L.Ed.2d 497, 509 (U.S. Jun. 23, 2017). This principle goes beyond the eminent domain issues in Murr v. Wisconsin. Many HOAs and condominiums boards or property managers are eager to make decisions for (or ignore their duties to) owners. In the old days, legal enforcement of restrictive covenants was troublesome and uncertain. In recent decades, state legislatures made new rules favoring restrictive covenants. Sometimes owners seek to do something with their property that violates an unambiguous, recorded covenant. I don’t see that scenario as the main problem. What I dislike more is community associations breaching their specific obligations to owners, as enshrined in governing documents or state law. Is the ability to enforce the covenants or law mutual? Are legal remedies of owners and HOAs equitable?

Why HOAs Wanted the Power to Fine:

Take an example. Imagine a property owner decides that it would be easier to simply dump their garbage in the backyard next to a HOA common area than take it to the landfill. Let’s assume that does not violate a local ordinance. Or substitute any other example where a property owner damages the property rights of others and the problem cannot be solved by a single award of damages. Before legislatures adopted certain statutes, the association would have to bring a lawsuit against the owner, asking the court to grant an injunction against the improper garbage dumping. This requires a demand letter and a lawsuit asking for the injunction. The association would have to serve the owner with the lawsuit. The owner would have an opportunity to respond to the lawsuit and the motion for the injunction. An injunction is a special court remedy that requires special circumstances not available in many cases. The party seeking it must show that they cannot be made whole only by an award of damages. The plaintiff must show that the injunction is necessary and would be effective to solve the problem. The legal standard for an injunction is higher than that for money damages, but it is not unachievably high. Courts grant injunctions all the time. However, the injunction requires the suit to be filed and responded to and the motion must be set for a hearing. Sometimes judges require the plaintiff to file a bond. Injunction cases are quite fact specific. The party filing the lawsuit must decide whether to wait for trial to ask for the injunction (which could be up to one year later) or to seek a “preliminary” or “temporary” injunction immediately. If the judge grants the injunction against the “private landfill,” the defendant may try to appeal to the state supreme court during these pretrial proceedings. These procedures exist because property right protections run both ways. Those seeking to enjoin the improper dumping have a right, if not a duty, to promote health and sanitation. Conversely, the owner would have a due process right to avoid having judges decide where she puts her trash on her own property. If the court grants the injunction, the judge does not personally supervise the cleanup of the dumping himself. If an order is disobeyed, the prevailing party may ask for per diem monetary sanctions pending compliance. That money judgment can attach as a lien or be used for garnishments. These common law rules have the effect of deterring the wrongful behavior. This also deters such lawsuits or motions absent exigent circumstances. Owners best interests are served by both neighbors properly maintaining their own property and not sweating the small stuff.

Giving Due Process of Court Proceedings vs. Sitting as both Prosecutor and Judge:

If association boards had to seek injunctions every time they thought an owner violated a community rule, then the HOAs would be much less likely to enforce the rules. The ease and certainty of enforcement greatly defines the value of the right. Boards and committees do not have the inherent right to sit as judges in their own cases and award themselves money if they determine that an owner violated something. That is a “judicial” power. Some interested people lobbied state capitals for HOAs to have power to issue fines for the violation of their own rules. To really give this some teeth, they also got state legislatures to give them the power to record liens and even foreclose on properties to enforce these fines.

Statutory Freeways Bypass the Country Roads of the Common Law: