May 16, 2014

What Difference Does It Make? Technical Breaches By Banks in Foreclosure

If a bank makes a technical error in the foreclosure process, what difference does it make? This blog post explores new legal developments regarding the materiality of breaches of mortgage documents. Residential foreclosure is a dramatic remedy. A lender extended a large sum of credit. Borrowers stretch themselves to make a down payment, monthly payments, repairs, association dues, taxes, etc. If financial hardships present obstacles to borrowers making payments, usually they will do what they can to keep their home.

In order to foreclose, lenders must navigate a complex web of provisions in the loan documents and relevant law. Note holders frequently commit errors in processing a payment default through a foreclosure sale. Sometimes these breaches are flagrant, such as foreclosing on a property to which that lender does not hold a lien. Usually they are less significant in the prejudice to the borrower’s rights. For example, written notices may not follow contract provisions or regulations verbatim, or a notice went out a day late or by regular mail instead of certified mail. Regardless of their significance, these rules were either willingly adopted by the parties or represent public policies reduced to law.

When homeowners challenge foreclosures in Court, lenders frequently argue in defense that the errors committed by the bank in the foreclosure process are not material. One could express this argument in another way by quoting the title lyric to British band The Smiths’ 1984 song, “What difference does it make?” The lenders typically highlight that the borrowers fell behind on their payments, did not come current, and do not have a present ability to come current on their loans. Borrowers face an uphill battle convincing judges to set aside or block foreclosure trustee sales or award money damages for non-material breaches. However, last month, two new court opinions illustrate a trend towards allowing remedies to homeowners for technical breaches. A relatively small award of money damages may not give homeowners their house back, but it may provide some consolation to the borrower and provide an incentive to mortgage investors, servicers and foreclosure trustees to strengthen their compliance programs.

When homeowners challenge foreclosures in Court, lenders frequently argue in defense that the errors committed by the bank in the foreclosure process are not material. One could express this argument in another way by quoting the title lyric to British band The Smiths’ 1984 song, “What difference does it make?” The lenders typically highlight that the borrowers fell behind on their payments, did not come current, and do not have a present ability to come current on their loans. Borrowers face an uphill battle convincing judges to set aside or block foreclosure trustee sales or award money damages for non-material breaches. However, last month, two new court opinions illustrate a trend towards allowing remedies to homeowners for technical breaches. A relatively small award of money damages may not give homeowners their house back, but it may provide some consolation to the borrower and provide an incentive to mortgage investors, servicers and foreclosure trustees to strengthen their compliance programs.

Content of Written Notices Required by Mortgage Documents:

On June 13, 2010, Wells Fargo Bank sent Bonnie Mayo a letter telling her he was in default on her mortgage on her Williamsburg residence. The letter indicated that if she failed to cure within 30 days, Wells Fargo would proceed with foreclosure. The letter informed her that, “[i]f foreclosure is initiated, you have the right to argue that you did keep your promises and agreements under the Mortgage Note and Mortgage, and to present any other defenses you may have.” However, the Mortgage required the lender to state in the written notice the borrower’s “right to reinstate after acceleration and right to bring a court action to assert the non-existence of a default or any other defense of Borrower to acceleration and sale.” Ms. Mayo’s notice did not include this language. She did not bring a lawsuit until after the date of the foreclosure sale.

In her post-foreclosure lawsuit, Mayo alleged (among other claims) that this breach entitled her to rescind the foreclosure and receive money damages. Wells Fargo moved to dismiss this claim on the grounds that the difference between the contractually required language and the actual letter was immaterial. In an April 11, 2014 opinion, Judge Raymond Jackson observed that just because a breach is non-material does not mean it is not a breach at all. He reached a conclusion contrary to a relatively recent opinion of another judge in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Virginia courts recognize claims to set aside foreclosure sales for “weighty” reasons but not “mere technical” grounds. Judge Jackson suggested that the bar may be higher for a homeowner to set aside a foreclosure sale after it occurs than to block it from happening in the first place. The Court declined to dismiss this claim on the sufficiency of the notices. Judge Jackson found that the materiality of this breach was a factual dispute requiring additional facts and argument to resolve.

A foreclosure is less susceptible to legally challenge after a subsequent purchaser goes to closing. Thus, the bank’s omission of language informing the borrower of her right to sue prior to the foreclosure carried a heightened potential for prejudice. Whether Ms. Mayo had a likelihood of prevailing in an earlier-filed lawsuit is a different story.

Failure to Conduct a Face-to-Face Meeting Prior to Foreclosure:

In 2002, Kim Squire King financed the purchase of a home in Norfolk, Virginia, with a Virginia Housing Development Authority mortgage. Her loan documents incorporated U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development regulations requiring a lender to make reasonable efforts to arrange a face-to-face interview with the borrower between default and foreclosure. Loss of employment caused King to go into default on her VHDA loan in March 2010. VHDA never offered King a face-to-face meeting. VHDA instituted foreclosure wherein the trustee sold King’s property to a third-party.

King filed a lawsuit seeking money damages and an order rescinding the foreclosure sale. The judge in Norfolk agreed with defense arguments that the error was not grounds to set aside the completed foreclosure or award compensatory damages. The court dismissed the lawsuit. Squire appealed to the Supreme Court of Virginia. The Justices upheld the dismissal of her request to set aside the completed foreclosure sale. The lawsuit failed to allege facts sufficient to show that the sale was fraudulent or grossly inadequate.The Supreme Court distinguished King’s situation from legal precedents where the borrower filed suit prior to the foreclosure. Surprisingly, the Court found that the trial judge erred in dismissing King’s claim for money damages arising out of the failure to arrange the face to face meeting. The Justices remanded the case to proceed on the damages issue.

When mortgage servicers and foreclosure trustees commit technical errors, what difference does it make? These new legal decisions show increasingly nuanced analysis of these particular issues. The materiality of the lender’s breach depends on a number of factors, including:

- The borrower’s apparent ability to reinstate the loan. If it is unlikely that the homeowner will get back on track, denying the bank foreclosure makes less sense.

- Did the borrower file suit before or after the foreclosure sale? A lawsuit can delay a foreclosure until the borrowers enforce their rights under the loan documents and incorporated regulations. However, unless the borrowers have a strategy to work-out the distressed loan or otherwise favorably dispose of the property, a pre-foreclosure lawsuit may only delay.

- The relationship between the technical error and the relief requested by the borrower. For example, if the loan documents require a notice to go out by certified mail and it only goes out by first class mail, but the borrower received it anyway, then there isn’t any prejudice.

- Money damages suffered by the borrower that arose out of the technical breach. Borrowers seek to keep their homes and to pay according to their abilities. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia and the Supreme Court of Virginia show an increasing willingness to hold lenders monetarily responsible for prejudicial lender breaches in the foreclosure process. A legal claim that partially offsets the lender’s judgment for the balance of the loan post-foreclosure may provide some consolation but may not avoid bankruptcy.

Discussed Case Opinions:

Mayo v. Wells Fargo Bank, No. 4:13-CV-163 (E.D.Va. Apr. 11, 2014)(Jackson, J.)

Squire v. Virginia Housing Development Authority, 287 Va. 507 (2014)(Powell, J.)

photo credit: Fabio Bruna via photopin cc

May 6, 2014

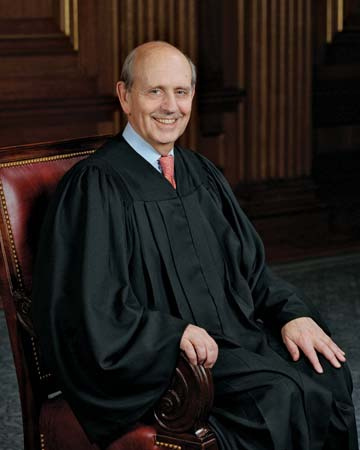

Mortgage Fraud Shifts Risk of Decrease in Value of Collateral in Sentencing

On March 5, 2014, I blogged about the oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court in U.S. v. Benjamin Robers, a criminal mortgage fraud sentencing appeal. At stake was how Courts should credit the sale of distressed property in calculating restitution awards. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit interpreted the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act to apply the sales price obtained by the bank selling the property post foreclosure as a partial “return” of the defrauded loan proceeds. Robers appealed, arguing that he was entitled to the Fair Market Value of the property at the time of the foreclosure auction. According to Robers, the mortgage investors should bear the risk of market fluctuations post-foreclosure because they control the disposition of the collateral. See Mar. 5, 2014, How Should Courts Determine Mortgage Fraud Restitution?

Yesterday, the Supreme Court affirmed the re-sale price approach in a unanimous decision. The Court observed that the perpetrators defrauded the victim banks out of the purchase money, not the real estate. The foreclosure process did not restore the “property” to the mortgage investors until liquidation at re-sale.

The Court focused on defense arguments that the real estate market, not Robers, caused the decrease in value of collateral between the time of the foreclosures and the subsequent bank sales. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote that:

Fluctuations in property values are common. Their existence (through not direction or amount) are foreseeable. And losses in part incurred through a decline in the value of collateral sold are directly related to an offender’s having obtained collateralized property through fraud.

Breyer distinguished “market fluctuations” from actions that could break the causal chain, such as a natural disaster or decision by the victim to gift the property or sell it to an affiliate for a nominal sum. See Lance Rogers, May 6, 2014, BNA U.S. Law Week, “Justices Clarify that Restitution ‘Offset’ is Gauged at Time Lender Sells Collateral.”

Falsified mortgage applications cause a lender to make a loan that it would not otherwise extend. A restitution award mirroring what the lender would receive in a civil deficiency judgment is inadequate. The defendant’s conduct opened the door for the Court to shift the risk of post-foreclosure market fluctuation from the bank to the borrower. Robers did not single-handedly render the local real estate market illiquid. However, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor mentions in her concurrence, real estate takes time to liquidate. These banks did not unreasonably delay the liquidation process. The Court opinion did not mention the prominent role of origination fraud in the subprime mortgage crisis. The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision strongly rejected defense arguments that downward “market fluctuations” severed the causal connection between the origination fraud and the depressed sales prices obtained by the lenders.

The Court did not discuss the original purchase prices for Robers’ two homes. In many mortgage fraud schemes, loan officers find “straw purchasers” such as Mr. Robers for sellers who agree to provide kickbacks on the inflated sales prices. See Mar. 15, 2009, Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, “Amid Subprime Rush, Swindlers Snatched $4 Million.” The perpetrators do not disclose these kickbacks to the lenders. The mortgage originators also receive origination fees from the lenders on the fraudulent closings. Under this arrangement, the purchase price will naturally reflect the highest sales price the bank’s appraiser will support. The bank is defrauded both by the fictitious qualifications of the borrower and the exaggerated sales prices.

U.S. v. Robers may result in stricter, more consistent restitution awards in mortgage fraud cases. I wonder how it will be applied in cases where the defendant presents stronger evidence that the victims acted unreasonably in liquidating the property. The opinion seems to leave discretion to District Courts to determine whether a bank’s conduct or omissions breaks the connection between the mortgage fraud and the sales price.

March 6, 2014

How Should the Courts Determine Mortgage Fraud Restitution?

James Lytle and Martin Valadez ran a mortgage fraud operation. They submitted falsified applications and loan documents to mortgage lenders to finance the sale of real estate to straw purchasers. For procuring the purchasers and loans, Messrs. Lytle & Valadez obtained kickbacks from the sellers out of proceeds of the sales. See Mar. 15, 2009, “Amid Subprime Rush, Swindlers Snatch $4 Million.” Benjamin Robers was one of these “straw men.” Mr. Robers signed falsified mortgage loan documents for the purchase of two homes in Walworth County, Wisconsin. Lytle & Valadez paid Robers $500 per transaction.

Robers soon fell into default under the loans. A representative of the Mortgage Guarantee Insurance Corporation (“MGIC”) testified about its losses and those of Fannie Mae regarding one of the properties. American Portfolio held the lien on the other property. Robers pleaded guilty (as did Lytle & Valadez). In Robers’ sentencing, the Federal District Court based the offset value of the real estate on the prices obtained by the financial institutions in the post-foreclosure out-sales. The court ordered restitution of $166,000 to MGIC and $52,952 to American Portfolio.

What is restitution? Restitution is the restoration of the property to the victim. The term also encompasses substitute compensation when simply returning the defrauded property is not feasible. For mortgage fraud restitution, the outstanding balance on the loan is easy to calculate. More difficult is adjusting the loan balance for the foreclosure. In a criminal case, how much of an off-set is the defendant entitled for the home when the bank forecloses on it? On February 25, 2014, lawyers argued this question before the U.S. Supreme Court. Later this term, the Court will decide how to offset the foreclosure against the loan amount. Defendant Robers argues that the proper amount is the fair market value of the property on the date of the foreclosure. The government and the victim banks maintain that it should be the price that the bank actually sells the property to the next owner.

U.S. v. Benjamin Robers:

These questions came before the Court in Benjamin Robers’ an appeal from the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals and the Eastern District of Wisconsin. Robers argued that the Court wrongfully held him responsible for the decline in value of the homes between the dates of the foreclosure and the out-sales. He wants the Fair Market Value (“FMV”) of the property on the date of the foreclosure to serve as the proper off-set amount in the restitution award.

U.S. Mandatory Victims Restitution Act:

Under the Federal Mandatory Victims Restitution Act, when return of the property to the victim is impractical, the monetary award shall be reduced by, “the value (as of the date the property is returned) of any part of the property that is returned.” 18 U.S.C. section 3663A(b)(1). In mortgage fraud, the real estate is collateral. Usually the lender does not convey real estate to the defendant in the original sale. Rather, the defendant defrauded the lender out of the purchase money. At what point during the foreclosure process is the “property” “returned” to the victim? In oral argument, some of the Justices didn’t seem entirely convinced that the statutory return of the property language even applies. Justice Scalia observed that the banks were not actually defrauded out of money; the money went to the sellers. The banks thought they were getting a borrower who was more likely to repay over the course of the loan than he actually was.

Robers argues that since title passes to the lender at the foreclosure, that is the “date the property is returned” for purposes of calculating restitution. He argues that Fair Market Value of the property at the time of the foreclosure is the proper off-set amount. This is consistent with decisions of some federal appellate courts.

Foreclosures in Virginia:

Note that in Virginia, and in some other states also practicing non-judicial foreclosure, formal title does not pass at the foreclosure sale. That is when the auction occurs and the bank or other purchaser acquires a contractual right to the auctioned property. The bank or other purchaser disposes of the property after obtaining a deed from the foreclosure trustee.

Government Sides with Victimized Lenders:

In Robers, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the government and the financial institutions. The court pointed out that banks are in the money business, not the real estate investment business: “The two cannot be equated. Cash is liquid. Real estate is not.” Obtaining title to the real estate collateral at the foreclosure sale gives the bank something that it must take further steps to liquidate into cash that can be re-invested elsewhere. As the new owner of the property, the lender must cover management, taxes, utilities, insurance and other carrying costs. Any improvements to the property likely suffer depreciation during any unoccupied period.

The Seventh Circuit observed that the Courts which adopt a contrary position ignore, “the reality that real property is not liquid and, absent a huge price discount, cannot be sold immediately.” What is the relationship between the liquidity of real estate and a Fair Market Value appraisal? Federal law contains a definition of FMV:

‘The fair market value is the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or to sell and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.’ 26 C.F.R. Sect. 20.2031-1(b), cited in, U.S. v. Cartwright, 411 U.S. 546, 551 (1973).

The FMV of property, “. . . is not determined by a forced sale price.” 26 C.F.R. Sect. 20.2031-1(b) The price to liquidate property immediately would be a forced sale, and hence not represent FMV. An appraisal seeks to value real estate in cash terms. If the seller makes dramatic compromises on price to sell a property immediately, that same is not a good comparable sale in a FMV approach.

The Seventh Circuit decided that “Robers, not his victims, should bear the risks of market forces beyond his control.” A bank agrees to accept real estate as collateral for a loan on the premise that the loan application is not fraudulent. A bank is in the real estate investment business when it lends money under these circumstances. The risk that it may become saddled with a foreclosure property later is managed in its underwriting process. In the case of fraud, the “you asked for collateral, now you get collateral” defense is not appropriate. Participants in organized mortgage fraud will not be deterred if the restitution award includes no more than a deficiency judgment awarded in a civil case.

The Seventh Circuit equates “FMV at the foreclosure date” with “liquidation at the foreclosure date.” However, the FMV approach seeks to avoid the downward pressures on price associated with compelled liquidation. The Seventh Circuit does not discuss the FMV method in detail. They likely inferred that the financial institution lenders would incur carrying costs between the foreclosure and the future date when the market allows the property to be sold for near FMV. When a neighborhood suffers from a rash of foreclosures, appraisers may struggle finding useful comparable sales that aren’t short sales, deeds-in-lieu or foreclosures.

Daniel Colbert, blogger for the American Criminal Law Review, points out that the bank has greater control over how market changes affect the out-sale price than the defendant’s fraud. Nov. 26, 2013, Foreclosing Restitution: When Has a Lender’s Property Been Returned? If the victim still owns the foreclosed property at the time the court sentences restitution, does it get both the house and the full restitution award? Such a result seems unlikely with most institutional lenders. Justice Breyer suggested that in such a case, the court would require an appraisal if the lender doesn’t want to sell within 90 days after sentencing.

Interest of Mortgage Investors in U.S. v. Robers:

Unfortunately, mortgage fraud schemes like Lytle & Valadez’s occurred in Virginia as well. Financial institutions holding mortgages on distressed properties cannot wait upon the outcome of a mortgage fraud prosecution. They must timely represent the interests of their investors. When to foreclose and re-sell the property is a business decision. A Supreme Court decision in favor of the government would strengthen mortgages as an investment. Tougher restitution awards would deter perpetrators of mortgage fraud. Mortgage investors can mitigate their losses in mortgage fraud cases by documenting the expenses they incur as a result of the fraud. To the extent such a borrower has any ability to pay, he will heed a restitution sentence more than an ordinary deficiency judgment.

photo credit: Marxchivist via photopin cc

January 31, 2014

Cold Temperatures in a Slow Economy: Insurance Claims from Frozen Pipes in Unoccupied Buildings

NBC News reported Wednesday that home insurance claims for damage resulting from frozen pipes are so high that insurers are hiring temporary adjusters to handle increased claims:

“We anticipate a large spike in frozen pipe claims,” said Peter Foley, the [American Insurance Association’s] vice president for claims. “In Washington, D.C., some of my colleagues have already had them in their own homes.”

What State Farm describes as a “catastrophe” comes while many families & communities struggle to make ends meet under the current economic conditions. These insurance claims can run as high as $15,000 in residential dwellings. A commercial property or multi-family housing can sustain even greater damages.

In many communities in Virginia, homes and commercial buildings remain vacant this winter because the local real estate market has not yet come back or the properties are only used seasonally. Frozen pipe damage is compounded in vacant buildings because:

- Few occupants take precautions to protect pipes from bursting before they move out of a building.

- Usually no one checks up on an unoccupied building when it is extremely cold. If there is a landlord, property manager, bank or other institutional investor, they aren’t likely to give a vacant building individual attention.

- No one is there to observe the damage as it develops, so greater drywall, carpet, mold, and other damage can occur.

These types of problems tend to result in litigation between the owners, banks, neighbors and insurance companies. This blog post explores three recent cases:

Hiring a Property Manager: Panda East Restaurant, Massachusetts

From 1987-2006, Issac Chow owned and operated the Panda East restaurant in Northampton, MA. Mr. Chow also purchased a house in Hadley, MA, for his employees to live in. While the restaurant was in business, Richard Lau managed both the restaurant and the house. When Panda East went out of business, all of its employees moved out of the house. Chow instructed Lau to keep the heat on in the Hadley house during the winter of 2006-07. Unfortunately, that winter the house suffered damage from burst frozen pipes. An inspector determined that the heat had been turned off. The flooding ruined carpets, furniture and drywall throughout the house.

Mr. Chow brought suit against Merrimack Mutual Fire Insurance Company in Massachusetts. On appeal, the Court could not determine what Chow did, if anything, to engage Lau as property manager for the house after the restaurant closed down. Since the employment relationship between Chow and Lau was unclear, the Court could not determine who was negligent. Chow v. Merrimack Mut. Fire Ins. Co., 83 Mass. App. Ct. 622 (2013). The Panda East case shows that:

- Cold winters are a time bomb to an unoccupied house (or other building) not winterized to prevent frozen pipes.

- Owners must consider retaining a manager or house-sitter for properties that “go dark.”

- Written property management agreements work better than verbal directions. A contract document can clearly define the scope of the manager’s responsibility.

Homeowner’s Negligence: Potomac, Maryland

In addition to suing the insurance company, some lawyers try to sue public utilities for damages arising from frozen pipes in an abandoned home. Izatullo Khosmukhamedov and Zoulfia Issaeva brought a lawsuit against Potomac Electric Power Co. (PEPCO) for leaving the electricity on in their unoccupied house, which later suffered damage from burst frozen pipes.

These Plaintiffs primarily lived in Moscow, Russia. This couple owned a second home in Potomac, Maryland. Apparently, they grew tired of paying the heating and electric bills. After a stay in October 2008, they sought to turn all of these services off. In the following winter, the pipes in the house froze, burst and caused extensive damage. They made no effort to winterize, heat the property, turn off the water main or drain the pipes. In their lawsuit, they argued that PEPCO failed to completely turn-off the electricity, thus allowing the well water pump to push water into the house, intensifying the damage.

The Federal judge in Maryland dismissed their claims on summary judgment before trial, observing that:

It is well-settled, both in Maryland and other jurisdictions, that a property owner can reasonably foresee the danger that water pipes may freeze in the winter and breaches the duty of ordinary care by failing to adequately heat and/or drain them.

Koshmukhamedov v. PEPCO, No. 8:11-cv-00449-AW (D. Md. Feb. 19, 2013)

Judge Williams dismissed Plaintiffs’ claim against PEPCO. This case illustrates skepticism shown to Plaintiffs in frozen pipe cases where they failed to take reasonable precautions.

Most residential property insurance policies specifically exclude coverage if the property goes unoccupied. In a related case, this couple also sued their property insurer, State Farm. The same judge decided that the home was “unoccupied” and thus excluded from coverage by the terms of the policy. Koshmukhamedov v. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., 946 F. Supp. 2d 443 (D. Md. May 28. 2013)

Insurance Claims in Foreclosure: Holiday Inn Express, Burnet, Texas

On our road trip, dear reader, we first warmed ourselves up with an a la carte dim sum brunch in Massachusetts. For lunch, we had a backfin crabcake in Maryland. The last stop on our trip takes us to a beef brisket dinner in central Texas. Our final case study shows how cashflow and property damage can compound problems for a business owner facing foreclosure. This double whammy presents special challenges to the bank and property insurer as well.

In late 2009, a Holiday Inn Express franchisee stopped making its mortgage payments to the bank that had lent the money for the purchase of the hotel building in Burnet, Texas. On January 9, 2010, the hotel suffered extensive damage from frozen pipes. On January 28, 2010, the bank sent the owner a foreclosure notice. A few days later, the property insurer sent the owner and bank a payment check. This was not cashed due to the disputes between the bank and owner. The owner and the insurance company could not agree on a proper estimate for the damage from the frozen pipes.

On March 2, 2010, the bank foreclosed on the property and purchased it at the sale. The hotelier then sued the bank, insurance company and the subsequent purchaser. The former owner sued the insurance company for not fully compensating for the damage he alleged to be $133,681.62. The Court of Appeals of Texas focused on relevant language in the insurance company’s contract with the owner and the Bank’s loan documents for the hotel. Lenders typically require borrowers to maintain adequate insurance on the property. That way, the loan is adequately secured in the event that damage and default occur around the same time. Usually, a lender’s rights to the security under the loan documents are limited to the principal, interest and other indebtedness owed. A claim for insurance proceeds comes into play to the extent the foreclosure sale price does not satisfy the sums of money owed to the bank.

In Virginia, the foreclosure trustee must file an accounting with the commissioner of accounts that reconciles the indebtedness, sale price and other credits and debits that the bank is entitled to under the loan documents and law. Each state has its own foreclosure procedures.

The Texas Court of Appeals explained that the Bank was only entitled to any portion of the insurance claim proceeds necessary to satisfy any deficiency after the foreclosure. It appears that the Court sought to avoid a windfall to any party seeking to muscle the proceeds during the chaotic foreclosure period. Peacock Hospitality, Inc. d/b/a Holiday Inn Express-Burnet, 419 S.W.3d 649 (Ct. App. Tex. Nov. 27, 2013)

Neither foreclosures nor frozen pipe damage occur in a vacuum. An exceptionally focused owner might take measures to prevent catastrophic damage to a distressed property in an attempt to fetch the highest possible foreclosure sale price. When a property is in financial distress, its owners and lenders must also attend to any signficant insurance claims that may become an element of the foreclosure accounting.

Conclusion:

These three cases illustrate why, as attorney Jim Autry says, “An abandoned building is more of a liability than an asset.” Frozen pipes present a serious threat to the value and habitability of unoccupied homes and commercial buildings. Except for a few “hot” areas, much of Virginia (and the country at large) has a significant inventory of uninhabited homes and commercial properties. This winter’s cold spells present unique challenges to property managers, water utilities, banks, owners and insurance companies. When a family or business must negotiate with more than one of these parties to resolve legal issues surrounding a distressed property, an experienced attorney can provide critical counseling and representation.

photo credit:

Ryan D Riley via photopin cc (for demonstrative purposes only and does not depict any of the actual properties described in this article)