May 14, 2015

You May Be Targeted for Condominium Termination

When I was in grade school, one of the most discussed films was The Terminator (1984). Long before he became the “governator” of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger starred as a cyborg from 2029. A world-dominating cloud computing program sent the Terminator to assassinate the future mother of the leader destined to save humanity. Growing up in a family with four kids, my parents didn’t take us to the theater too often, especially ones like that. I initially learned about the Terminator through oral accounts from my classmates. In 2015, we are now about halfway to the date of the fictional dystopia that this monster came from. Luckily, we don’t have to deal with time-traveling robotic assassins yet. While this movie was science fiction, it was popular because it triggers fight-or-flight emotional responses from its audience.

In the world of condominiums, the threat of ownership termination creates fear, hardship and uncertainty. It is the job of owner’s counsel not to defeat robots but to provide counseling and advocacy to protect hard-earned property rights.

What is condominium termination? One of the unique features of condominium law is that under the law of many states, including Virginia, a super-majority of unit owners have the right to sell all of the units and common areas to an investor without the consent of the dissenting owners and directors. Condominium owners share walls, floors, ceilings, roofs, structural elements, and foundations with their neighbors, and these things can all fall apart. It makes sense to have a legal mechanism to address dire situations where the entire condominium can be liquidated so owners can cut their losses.

These legal procedures typically start with a super-majority, usually it is around 80%, adopting a formal plan of termination. Usually the Board of Directors of the association becomes the trustee of all of the property in termination. The Board hires appraisers to determine the fair market value of the individual units. The trustee enters into a contract with a purchaser for all of the real estate. The mortgage lenders, attorneys, settlement agents, appraisers, unit owners, etc. are all paid out of the proceeds of the sale to the investor. The termination provisions of the Condominium Act and the governing documents of the association provide framework for the process. On paper, the concept of condominium termination sounds like a reasonable accommodation for a super-majority consensus to address an extreme situation.

Unfortunately, now investors use the condominium termination statutes in ways that were probably not anticipated by the legislatures. Prior to the collapse of the real estate market in 2008, investors and developers converted many apartment buildings and hotels to condominiums. When the condominium market deteriorated, many associations found themselves with one investor owning a large number of units. The “bulk owner” controlled the association through its super-majority votes in owners meetings and on the board of directors. Certainly a less than ideal situation, especially for owner-occupants.

The bulk owners discovered the condominium termination statute. With their super majority votes, they had a legal theory upon which to sell all the units, including those of the minority owners to an investor, usually a business affiliate of the same bulk owner. Because the bulk owner controls the board of directors, they influence which appraisers calculate the respective values of the units. They also control the total purchase price where the bulk owner is, practically speaking, selling everything to itself.

The potential for self-dealing and abuse of property rights is obvious. The bulk owner naturally wants the unit appraisals and the overall purchase price to be low, to make the transaction more profitable. The governance of the association provides no real checks and balances or oversight because of the super-majority interest. Many associations use the flow of documents and financial information strategically. In adversarial situations, it is common to make only the legally-minimum amount of disclosures. In terminations, individual owners are left wondering what is happening, why and what rights they have, if any.

In The Terminator film, the bodyguard for the human target of the robot explains to her: “Listen, and understand. That terminator is out there. It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear.” Unassisted by counsel, condo unit owners have a frustrating time trying to communicate with the other side in termination proceedings.

According to the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation, since 2007 there have been 279 condominium terminations in the Sunshine State alone. See May 4, 2015, Palm Beach Post, “Condo Owners Win Protections, but Do They Go Too Far?” Faced with public outcry over loss of their homes or retirement income at grossly inadequate compensation, the Florida legislature recently passed HB643 to reform the condominium termination statute. While I am not a Florida attorney, I have a few observations:

- The bill continues to allow termination of the condominium without a court proceeding. I would support legislation that would forbid non-judicial condominium terminations without direct court supervision, unless 100% of the owners sign off.

- Owners get an option to lease “their” unit after termination. In certain circumstances, they may qualify for relocation expenses. For an owner suffering a financial hardship through loss of their home or rental property, for some this may seem to add insult to injury.

- Qualifying owners may receive their original purchase price as compensation. This may not help everyone, because buyers normally seek the lowest purchase price. Owners don’t buy condos high in anticipation of a termination. See April 27, 2015 South Florida Business Journal, “Florida Bill Could Make it Tougher for Developers to Terminate Condo Associations.”

- The reform provides special protections for mortgage lenders designed to avoid situations where the borrower would be left with a deficiency on the loan. This doesn’t help owners who maintained responsible loan to value ratios.

- The bill strictly limits the ability of homeowners to contest the validity of the termination and the adequacy of the compensation. For example, the owner must petition for arbitration within 90 days of the termination. This is dramatically shorter than most limitation periods for legal claims. The new statute also limits the issues upon which the owner may contest the termination to the apportionment of the proceeds, the satisfaction of liens and the voting.

This statute revision provides additional detail about the respective rights of bulk and individual owners in condominium terminations. Unfortunately for the individual investors, it continues leaving the procedures (largely) self-regulated by the bulk investors and their advisors. The termination provisions in each state are different. Other state condominium acts may not address bulk ownership like Florida. Virginia’s hasn’t been revised since the 1990’s.

In order to terminate a marriage, corporation or other legal entity in a situation where the parties are deadlocked, usually the party seeking termination must file a lawsuit. If there is more than one owner on a deed to real estate, absent an agreement to the contrary, a suit must be filed before the parcel can be sold or sub-divided. Condominium terminations remain one of the few circumstances where super-majority owners have a procedure to self-deal in the property rights of minority stakeholders with little oversight.

If you own an interest in a condominium unit and received a notice indicating that another owner has proposed termination to the association, contact a qualified attorney immediately to obtain assistance to protect your rights. The application of state law and governing documents to the facts and circumstances are unique in each case.

I’ll be back (to this blog)!

photo credit: Richmond Skyline from 21st and East Franklin at Dusk via photopin (license)

May 6, 2014

Mortgage Fraud Shifts Risk of Decrease in Value of Collateral in Sentencing

On March 5, 2014, I blogged about the oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court in U.S. v. Benjamin Robers, a criminal mortgage fraud sentencing appeal. At stake was how Courts should credit the sale of distressed property in calculating restitution awards. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit interpreted the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act to apply the sales price obtained by the bank selling the property post foreclosure as a partial “return” of the defrauded loan proceeds. Robers appealed, arguing that he was entitled to the Fair Market Value of the property at the time of the foreclosure auction. According to Robers, the mortgage investors should bear the risk of market fluctuations post-foreclosure because they control the disposition of the collateral. See Mar. 5, 2014, How Should Courts Determine Mortgage Fraud Restitution?

Yesterday, the Supreme Court affirmed the re-sale price approach in a unanimous decision. The Court observed that the perpetrators defrauded the victim banks out of the purchase money, not the real estate. The foreclosure process did not restore the “property” to the mortgage investors until liquidation at re-sale.

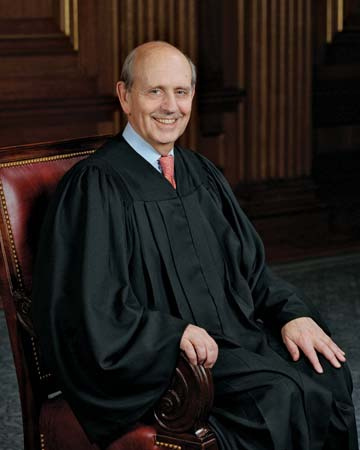

The Court focused on defense arguments that the real estate market, not Robers, caused the decrease in value of collateral between the time of the foreclosures and the subsequent bank sales. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote that:

Fluctuations in property values are common. Their existence (through not direction or amount) are foreseeable. And losses in part incurred through a decline in the value of collateral sold are directly related to an offender’s having obtained collateralized property through fraud.

Breyer distinguished “market fluctuations” from actions that could break the causal chain, such as a natural disaster or decision by the victim to gift the property or sell it to an affiliate for a nominal sum. See Lance Rogers, May 6, 2014, BNA U.S. Law Week, “Justices Clarify that Restitution ‘Offset’ is Gauged at Time Lender Sells Collateral.”

Falsified mortgage applications cause a lender to make a loan that it would not otherwise extend. A restitution award mirroring what the lender would receive in a civil deficiency judgment is inadequate. The defendant’s conduct opened the door for the Court to shift the risk of post-foreclosure market fluctuation from the bank to the borrower. Robers did not single-handedly render the local real estate market illiquid. However, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor mentions in her concurrence, real estate takes time to liquidate. These banks did not unreasonably delay the liquidation process. The Court opinion did not mention the prominent role of origination fraud in the subprime mortgage crisis. The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision strongly rejected defense arguments that downward “market fluctuations” severed the causal connection between the origination fraud and the depressed sales prices obtained by the lenders.

The Court did not discuss the original purchase prices for Robers’ two homes. In many mortgage fraud schemes, loan officers find “straw purchasers” such as Mr. Robers for sellers who agree to provide kickbacks on the inflated sales prices. See Mar. 15, 2009, Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, “Amid Subprime Rush, Swindlers Snatched $4 Million.” The perpetrators do not disclose these kickbacks to the lenders. The mortgage originators also receive origination fees from the lenders on the fraudulent closings. Under this arrangement, the purchase price will naturally reflect the highest sales price the bank’s appraiser will support. The bank is defrauded both by the fictitious qualifications of the borrower and the exaggerated sales prices.

U.S. v. Robers may result in stricter, more consistent restitution awards in mortgage fraud cases. I wonder how it will be applied in cases where the defendant presents stronger evidence that the victims acted unreasonably in liquidating the property. The opinion seems to leave discretion to District Courts to determine whether a bank’s conduct or omissions breaks the connection between the mortgage fraud and the sales price.

March 6, 2014

How Should the Courts Determine Mortgage Fraud Restitution?

James Lytle and Martin Valadez ran a mortgage fraud operation. They submitted falsified applications and loan documents to mortgage lenders to finance the sale of real estate to straw purchasers. For procuring the purchasers and loans, Messrs. Lytle & Valadez obtained kickbacks from the sellers out of proceeds of the sales. See Mar. 15, 2009, “Amid Subprime Rush, Swindlers Snatch $4 Million.” Benjamin Robers was one of these “straw men.” Mr. Robers signed falsified mortgage loan documents for the purchase of two homes in Walworth County, Wisconsin. Lytle & Valadez paid Robers $500 per transaction.

Robers soon fell into default under the loans. A representative of the Mortgage Guarantee Insurance Corporation (“MGIC”) testified about its losses and those of Fannie Mae regarding one of the properties. American Portfolio held the lien on the other property. Robers pleaded guilty (as did Lytle & Valadez). In Robers’ sentencing, the Federal District Court based the offset value of the real estate on the prices obtained by the financial institutions in the post-foreclosure out-sales. The court ordered restitution of $166,000 to MGIC and $52,952 to American Portfolio.

What is restitution? Restitution is the restoration of the property to the victim. The term also encompasses substitute compensation when simply returning the defrauded property is not feasible. For mortgage fraud restitution, the outstanding balance on the loan is easy to calculate. More difficult is adjusting the loan balance for the foreclosure. In a criminal case, how much of an off-set is the defendant entitled for the home when the bank forecloses on it? On February 25, 2014, lawyers argued this question before the U.S. Supreme Court. Later this term, the Court will decide how to offset the foreclosure against the loan amount. Defendant Robers argues that the proper amount is the fair market value of the property on the date of the foreclosure. The government and the victim banks maintain that it should be the price that the bank actually sells the property to the next owner.

U.S. v. Benjamin Robers:

These questions came before the Court in Benjamin Robers’ an appeal from the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals and the Eastern District of Wisconsin. Robers argued that the Court wrongfully held him responsible for the decline in value of the homes between the dates of the foreclosure and the out-sales. He wants the Fair Market Value (“FMV”) of the property on the date of the foreclosure to serve as the proper off-set amount in the restitution award.

U.S. Mandatory Victims Restitution Act:

Under the Federal Mandatory Victims Restitution Act, when return of the property to the victim is impractical, the monetary award shall be reduced by, “the value (as of the date the property is returned) of any part of the property that is returned.” 18 U.S.C. section 3663A(b)(1). In mortgage fraud, the real estate is collateral. Usually the lender does not convey real estate to the defendant in the original sale. Rather, the defendant defrauded the lender out of the purchase money. At what point during the foreclosure process is the “property” “returned” to the victim? In oral argument, some of the Justices didn’t seem entirely convinced that the statutory return of the property language even applies. Justice Scalia observed that the banks were not actually defrauded out of money; the money went to the sellers. The banks thought they were getting a borrower who was more likely to repay over the course of the loan than he actually was.

Robers argues that since title passes to the lender at the foreclosure, that is the “date the property is returned” for purposes of calculating restitution. He argues that Fair Market Value of the property at the time of the foreclosure is the proper off-set amount. This is consistent with decisions of some federal appellate courts.

Foreclosures in Virginia:

Note that in Virginia, and in some other states also practicing non-judicial foreclosure, formal title does not pass at the foreclosure sale. That is when the auction occurs and the bank or other purchaser acquires a contractual right to the auctioned property. The bank or other purchaser disposes of the property after obtaining a deed from the foreclosure trustee.

Government Sides with Victimized Lenders:

In Robers, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the government and the financial institutions. The court pointed out that banks are in the money business, not the real estate investment business: “The two cannot be equated. Cash is liquid. Real estate is not.” Obtaining title to the real estate collateral at the foreclosure sale gives the bank something that it must take further steps to liquidate into cash that can be re-invested elsewhere. As the new owner of the property, the lender must cover management, taxes, utilities, insurance and other carrying costs. Any improvements to the property likely suffer depreciation during any unoccupied period.

The Seventh Circuit observed that the Courts which adopt a contrary position ignore, “the reality that real property is not liquid and, absent a huge price discount, cannot be sold immediately.” What is the relationship between the liquidity of real estate and a Fair Market Value appraisal? Federal law contains a definition of FMV:

‘The fair market value is the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or to sell and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.’ 26 C.F.R. Sect. 20.2031-1(b), cited in, U.S. v. Cartwright, 411 U.S. 546, 551 (1973).

The FMV of property, “. . . is not determined by a forced sale price.” 26 C.F.R. Sect. 20.2031-1(b) The price to liquidate property immediately would be a forced sale, and hence not represent FMV. An appraisal seeks to value real estate in cash terms. If the seller makes dramatic compromises on price to sell a property immediately, that same is not a good comparable sale in a FMV approach.

The Seventh Circuit decided that “Robers, not his victims, should bear the risks of market forces beyond his control.” A bank agrees to accept real estate as collateral for a loan on the premise that the loan application is not fraudulent. A bank is in the real estate investment business when it lends money under these circumstances. The risk that it may become saddled with a foreclosure property later is managed in its underwriting process. In the case of fraud, the “you asked for collateral, now you get collateral” defense is not appropriate. Participants in organized mortgage fraud will not be deterred if the restitution award includes no more than a deficiency judgment awarded in a civil case.

The Seventh Circuit equates “FMV at the foreclosure date” with “liquidation at the foreclosure date.” However, the FMV approach seeks to avoid the downward pressures on price associated with compelled liquidation. The Seventh Circuit does not discuss the FMV method in detail. They likely inferred that the financial institution lenders would incur carrying costs between the foreclosure and the future date when the market allows the property to be sold for near FMV. When a neighborhood suffers from a rash of foreclosures, appraisers may struggle finding useful comparable sales that aren’t short sales, deeds-in-lieu or foreclosures.

Daniel Colbert, blogger for the American Criminal Law Review, points out that the bank has greater control over how market changes affect the out-sale price than the defendant’s fraud. Nov. 26, 2013, Foreclosing Restitution: When Has a Lender’s Property Been Returned? If the victim still owns the foreclosed property at the time the court sentences restitution, does it get both the house and the full restitution award? Such a result seems unlikely with most institutional lenders. Justice Breyer suggested that in such a case, the court would require an appraisal if the lender doesn’t want to sell within 90 days after sentencing.

Interest of Mortgage Investors in U.S. v. Robers:

Unfortunately, mortgage fraud schemes like Lytle & Valadez’s occurred in Virginia as well. Financial institutions holding mortgages on distressed properties cannot wait upon the outcome of a mortgage fraud prosecution. They must timely represent the interests of their investors. When to foreclose and re-sell the property is a business decision. A Supreme Court decision in favor of the government would strengthen mortgages as an investment. Tougher restitution awards would deter perpetrators of mortgage fraud. Mortgage investors can mitigate their losses in mortgage fraud cases by documenting the expenses they incur as a result of the fraud. To the extent such a borrower has any ability to pay, he will heed a restitution sentence more than an ordinary deficiency judgment.

photo credit: Marxchivist via photopin cc