May 6, 2014

Mortgage Fraud Shifts Risk of Decrease in Value of Collateral in Sentencing

On March 5, 2014, I blogged about the oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court in U.S. v. Benjamin Robers, a criminal mortgage fraud sentencing appeal. At stake was how Courts should credit the sale of distressed property in calculating restitution awards. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit interpreted the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act to apply the sales price obtained by the bank selling the property post foreclosure as a partial “return” of the defrauded loan proceeds. Robers appealed, arguing that he was entitled to the Fair Market Value of the property at the time of the foreclosure auction. According to Robers, the mortgage investors should bear the risk of market fluctuations post-foreclosure because they control the disposition of the collateral. See Mar. 5, 2014, How Should Courts Determine Mortgage Fraud Restitution?

Yesterday, the Supreme Court affirmed the re-sale price approach in a unanimous decision. The Court observed that the perpetrators defrauded the victim banks out of the purchase money, not the real estate. The foreclosure process did not restore the “property” to the mortgage investors until liquidation at re-sale.

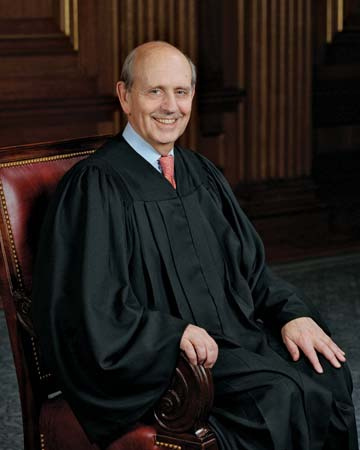

The Court focused on defense arguments that the real estate market, not Robers, caused the decrease in value of collateral between the time of the foreclosures and the subsequent bank sales. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote that:

Fluctuations in property values are common. Their existence (through not direction or amount) are foreseeable. And losses in part incurred through a decline in the value of collateral sold are directly related to an offender’s having obtained collateralized property through fraud.

Breyer distinguished “market fluctuations” from actions that could break the causal chain, such as a natural disaster or decision by the victim to gift the property or sell it to an affiliate for a nominal sum. See Lance Rogers, May 6, 2014, BNA U.S. Law Week, “Justices Clarify that Restitution ‘Offset’ is Gauged at Time Lender Sells Collateral.”

Falsified mortgage applications cause a lender to make a loan that it would not otherwise extend. A restitution award mirroring what the lender would receive in a civil deficiency judgment is inadequate. The defendant’s conduct opened the door for the Court to shift the risk of post-foreclosure market fluctuation from the bank to the borrower. Robers did not single-handedly render the local real estate market illiquid. However, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor mentions in her concurrence, real estate takes time to liquidate. These banks did not unreasonably delay the liquidation process. The Court opinion did not mention the prominent role of origination fraud in the subprime mortgage crisis. The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision strongly rejected defense arguments that downward “market fluctuations” severed the causal connection between the origination fraud and the depressed sales prices obtained by the lenders.

The Court did not discuss the original purchase prices for Robers’ two homes. In many mortgage fraud schemes, loan officers find “straw purchasers” such as Mr. Robers for sellers who agree to provide kickbacks on the inflated sales prices. See Mar. 15, 2009, Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, “Amid Subprime Rush, Swindlers Snatched $4 Million.” The perpetrators do not disclose these kickbacks to the lenders. The mortgage originators also receive origination fees from the lenders on the fraudulent closings. Under this arrangement, the purchase price will naturally reflect the highest sales price the bank’s appraiser will support. The bank is defrauded both by the fictitious qualifications of the borrower and the exaggerated sales prices.

U.S. v. Robers may result in stricter, more consistent restitution awards in mortgage fraud cases. I wonder how it will be applied in cases where the defendant presents stronger evidence that the victims acted unreasonably in liquidating the property. The opinion seems to leave discretion to District Courts to determine whether a bank’s conduct or omissions breaks the connection between the mortgage fraud and the sales price.