February 12, 2015

The Beginning of a Virginia Circuit Court Case

Many people will never be party to a lawsuit that goes to trial. For those that do, the first time may be the only time. Being a party to a Virginia circuit court civil case requires significant time, focus and resources for what may be several months or longer. What should a party expect from the beginning of a Virginia circuit court case? Because of the commitment required, parties to a lawsuit should familiarize themselves with the basics. This article is the first installment in a series providing a basic overview of Virginia circuit court civil cases. While the circumstances and details of each case are unique, the rules of court provide a basic outline of what to expect.

Pre-Lawsuit Negotiations: Before a lawsuit is filed, the parties and their attorneys usually communicate in efforts to achieve desired results without the necessity of a lawsuit. They exchange emails, demand letters, settlement offers and other correspondence articulating their interests, position and requirements. Why engage in this process if there already are grounds for a lawsuit? In the facts of many cases, there is a reasonable likelihood that the case can be settled without the necessity of filing suit. Not every case that ought to settle in fact resolves without filing suit. However, once suit is filed, the parties will be required to conduct the case in addition to engaging in any desired settlement negotiations. Often it is worthwhile to first see if things can be negotiated.

Filing the Complaint: If settlement negotiations don’t work, a party’s first step towards obtaining a judgment may be to file a complaint at the circuit court clerk’s office. In real estate and construction cases, this is usually done at the courthouse for the city or county where the property is located. Most real estate or construction cases are brought in Circuit Court. However, if the amount in controversy is $25,000.00 or less, the case will probably be brought in General District Court. Alternatively, some cases are brought in federal court.

To begin the case properly, the plaintiff’s best interests are served by investigating and analyzing the case with the lawyer. The complaint should include the proper parties with their correct names. The claims (e.g., breach of contract, breach of warranty, fraud, etc.) should be carefully considered and supported by sufficient factual allegations. The remedies (e.g., money judgment, declaration of rights, etc.) requested to the Court should be clear and supported by the claims. The parties defending the lawsuit can be expected to attack the complaint in whatever way they can. Making the complaint as strong as reasonably possible positions the plaintiff to have a greater likelihood of obtaining a favorable result in court or settlement. The plaintiff normally bears the burden of proof for the claims in the complaint. Parties should avoid simply putting some allegations together that merely forces the other side to respond. Time and focus spent on the complaint may prevent more time unnecessarily being spent strengthening or disputing over a claim later.

Service of Process: A lawsuit cannot proceed unless the defendants are formally put on notice. Normally this consists of having a sheriff’s deputy or private process server going out to each defendant’s house to serve them. There are several alternatives to direct hand delivery of the complaint on the defendant that may apply. Usually it takes a few days for the court personnel to process the paperwork. If the lawyers for the parties are already introduced, often the attorney will provide the defendants with a courtesy copy of the complaint before it is served.

Defendant’s Initial Response: Once the defendant is served, he normally has 21 days in which to respond. Failure to respond in a timely manner or obtain an extension can result in that party falling into default. Falling into default can result in significant waiver of rights to defend the lawsuit and possible entry of default judgment. Usually, defendants respond initially to complaints by filing a “demurrer” or some other motion designed to have the lawsuit dismissed. In the Virginia circuit courts, defendants often make substantial efforts in these early demurrers and motions. Unlike some other states, the defendant’s ability to get a case dismissed on a later pre-trial motion is limited in Virginia state courts. Since the plaintiff bears the burden of proving the allegations and generally upholding the legitimacy of the lawsuit, there are many possible grounds for a defendant to seek dismissal. What is a demurrer? At this stage the defendant usually cannot successfully challenge the truth of the facts asserted in the complaint. Instead, the demurrers typically argue that, for whatever reason, the complaint is not legally sufficient and must be revised or abandoned. For example, a plaintiff may allege various forms of wrongdoing and damages suffered. However, if a claim fails to properly articulate a causal connection between the wrongful conduct and the damages suffered, the defendant will probably argue that it is not legally sufficient. The demurrer or motion to dismiss may require a court hearing where the attorneys will argue before a judge over the sufficiency of the lawsuit. The parties themselves are usually not required to attend these hearings but may do so if they wish.

Defendant’s Answer and Affirmative Defenses: At the end of this initial motions practice phase, the defendants are usually left with claims that have survived and must be responded to directly. This is done by filing an answer containing numbered paragraphs responding directly to those in the complaint as admitted, denied or whatever other response is appropriate. In the same document, the defendants will also identify their affirmative defenses. For example, the defendant may assert fraud, that the plaintiff waived her rights by taking too long to file suit, or other defenses. Some affirmative defenses must be put with the answer to avoid being waived.

Additional Claims: A defendant may have a claim against the plaintiff, another defendant or a third party that may be related to the facts of the case. This initial response phase is the normal time for such claims to be asserted. A counter-claim, cross-claim or claim against a third party is in many respects treated like a separate lawsuit that will go to trial with the initial lawsuit because of the common factual issues.

Scheduling Orders and Trial Dates: Around this time the court will set the trial date. A party should provide her attorney with dates to avoid (vacation, travel, etc.) for trial. Additionally the attorney and client will discuss whether a trial by or without a jury should be requested. When the attorneys set the case for trial, the court may enter a scheduling order setting certain deadlines for the progress of the case. Once the trial date is set, the attorneys, parties and witnesses should reserve the trial dates on their calendars.

There is a lot of activity that goes on in a Virginia circuit court case before the parties give their own personal testimony. In the next installment in this series, I will provide an overview for the discovery process, where each side requests testimony, property viewings, documents and information from their opponents and third parties. The facts and circumstances of each case are different and may require additional procedures or other variations from the outline provided above. If you have a real estate or construction claim against another party, discuss the matter with a qualified attorney to avoid unnecessary waiver of any rights. If you have been made a defendant to a lawsuit, consult with an attorney admitted to practice before the court where the suit is filed to avoid falling into default or other waiver of rights.

January 29, 2015

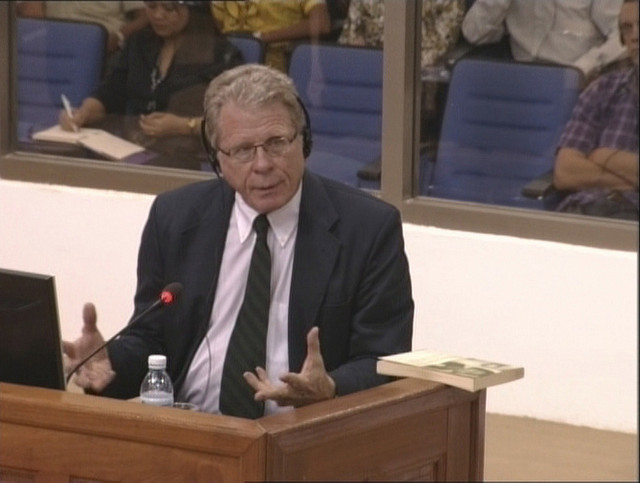

New Book Review: The Articulate Witness

One of the duties of a litigator is to prepare the client to testify at a deposition, mediation, hearing or trial. Clear, credible and cogent testimony puts the party in the best position to prevail. While judges, arbitrators and juries want to see the contracts and key documents, they also want to hear directly from the parties whose dispute is before the court.

Experienced trial attorneys know what to expect of themselves and their witnesses from the facts of the case. When it comes to public speaking, witness preparation typically includes discussion of the disputed facts and legal arguments in the case. While an attorney may not tell the client or witness what to say, he may ask practice examination questions. Witnesses quickly learn that courtroom or deposition testimony differs from ordinary conversation or interviews. A witness may have little or no public speaking training or experience. There may not be time for a witness to gain valuable experience in Toastmasters International or other activities to practice speaking skills. So how can a witness prepare herself to give effective testimony in her own case?

This month, Brian K. Johnson and Marsha Hunter published a new book, “The Articulate Witness: An Illustrated Guide to Testifying Confidently Under Oath.” This edition is available in print or e-book format. Johnson & Hunter are consultants who train attorneys for a variety of public speaking settings. I have read one of their other books and attended one of their seminars. “The Articulate Witness” is useful to parties and witnesses seeking an overview of the legal testimonial process. It is a valuable resource for attorneys and law students seeking insights in how to better prepare their clients to testify. Professional experts evaluating their own habits and skills would benefit as well. The book is a breezy 50 pages with copious illustrations. I finished it riding on the D.C. Metro between the Judiciary Square & West Falls Church stations. The book focuses on the mechanics of speaking confidently in litigation situations, including cross-examination. The book would be useful to a witness when they first know that a deposition, hearing, trial, etc. will occur. It is not a good book to read the evening before the big day. The reader may desire to practice some of the exercises or discuss them with the attorney beforehand. The book is not a proper substitute for trial preparation with one’s attorney.

A common mistaken belief is that public speaking involves only expressing one’s thoughts using one’s voice. Johnson & Hunter do a great job of showing how it is also a “physical” activity, involving posture, gestures, handling exhibit documents, facial expression and eye contact.

“The Articulate Witness” is an excellent reference for witnesses,attorneys, experts or any other person whose profession or circumstances require him to speak in a legal proceeding. Mastery of the facts and laws is not sufficient. One must be prepared to cogently communicate one’s position to others.

photo credit: Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia via photopin cc