February 20, 2015

The Basics of Civil Litigation Discovery

At some point after the filing of a lawsuit in Virginia Circuit Court, initial disputes over the sufficiency of the complaint are resolved. The parties are now on notice of their opponents’ claims and defenses. The process of getting to this point was the focus of my previous blog post. Contrary to what one sees on T.V. or movies, parties do not immediately proceed to going to trial. Instead, lawyers and their clients begin to prepare for trial in a period called “discovery.” Discovery involves finding out more facts about the case. This post provides an overview of the basics of civil litigation discovery, with a focus on its purposes and tools in real estate cases. Why is there such a lengthy process for this? Consider three purposes of discovery:

- Hoarding. Preventing one side or another from “hoarding” documents and information about the case to the unfair detriment of others. For example, in a case between different homeowners’ association factions over control of the board of directors, whoever happens to have access to the minutes, resolutions, notices, amendments, etc., kept by the association must provide them to the other.

- Surprises. Lawyers, as a lot, are attracted to springing surprises on their opponents at trial. However, it may be contrary to the principles of justice for one side to hand the other a large stack of documents they have never seen before during the trial and expect the witness questioning to be meaningful. Discovery can mitigate unfair surprise.

- Effectiveness of Trial. The public places greater confidence in trial results that are based on documents and facts rather than the decisions made in the absence of existing evidence.

The methods of discovery are more formal than the fact gathering conducted outside of litigation. Informal investigation includes researching the documents and information within one’s control, talking to friendly witnesses, checking what is publicly available or that one’s bank can provide. Usually this doesn’t answer all questions. So what are the available forms of civil discovery? There are quite a few. The most useful in real estate and construction cases in Virginia circuit court are:

- Document Requests. The rules allow a party to request in writing an opponent’s documents. A party seeking production of documents must send a written request. The responding party then has 21 days in which to respond as to documents within their possession, custody or control. In large cases it usually takes significantly longer than 21 days to resolve a document request. Reviewing the relevant documents of one’s opponent is a central element of trial preparation. Contracts and other documents created before the dispute cannot, absent forgery, be changed to adapt to someone’s current story. When the judge or jury goes to make determinations of facts, the credibility of the parties and the key documents carry great weight. If a party fails to produce a document requested in discovery, they are not normally allowed to use it as an exhibit at trial. The documents of a third-party can be requested by serving them with a subpoena duces tecum.

- Interrogatories. Information sought may not necessarily be reflected in a document. In discovery, a party may submit written interrogatories to another party, seeking answers to specific questions. For example, a party may inquire into the factual support for their opponent’s claims or defenses. Parties usually ask for disclosure of all persons having knowledge about the facts of the case. Interrogatories are also a good tool for finding out about expert testimony that one’s opponent may present at trial. The answering party must respond within 21 days. The answers must be signed by a party under oath or affirmation.

- Requests for Admissions. Last August, I posted an article about the role of a party’s admissions in a federal trial in Maryland. In that case, a lawyer made an oral admission in a closing argument. His opponent did not make a motion to have the admission deemed binding before the jury went to deliberate. The jury made a decision contrary to the admission. The jury verdict ignoring the admission survived post-trial motions and appeal. Party admissions can be requested in discovery before they come out at trial. Parties are entitled to submit to the opponent formal, written requests for admission. The 21 day deadline applies here as well. Admitted responses are binding. These can be useful for resolving uncontested matters so that the trial can focus on what’s disputed.

- Depositions. How will a party or witness react to a line of questions at trial? Does a party or witness know something that can be useful to preparing one’s own case? In discovery, a party may take oral depositions of parties, experts or other witnesses. The deposition usually occurs at a law office. The parties, the lawyers and the witness meet in a conference room with a court reporter. The court reporter places the witness under oath, and then records all of the lawyers’ questions, objections and witness answers. Depositions of parties and experts are an important part of pretrial discovery in large cases.

- View of Real Estate. In many real estate or construction cases, the most significant piece of evidence is the building or land itself. If ordered, the jury travels to the property to view it as evidence. More commonly, the appearance of property is put into evidence by photographs or video. A party not in possession or control of the real estate is entitled to view it. This can be an effective way of expanding one’s knowledge about the case.

Not all of these tools will need to be employed in every case. In addition to these forms of discovery, there are common areas where parties dispute over whether the discovery has been properly sought or provided. These are usually the subject of objections and motions:

- Relevance. Discovery cannot be used to explore any and every topic. The requests must explore relevant, admissible evidence or information that is reasonably calculated to lead to admissible evidence. Although not unlimited, the scope of discovery is broad.

- Confidentiality. A party may have confidentiality concerns about turning over documents or information. These concerns can be addressed by a protective order regulating the use and disposition of confidential documents or other information.

- Privileges to Withhold. Frequently attorneys will interpose objections to discovery requests. One justification for withholding documents is the attorney-client privilege. Communications between an attorney and his client are not subject to discovery. Despite the apparent simplicity of this concept, disputes over assertion of the attorney-client privilege are a frequent source of discovery disputes. There are other privilege and objections that are applicable in certain situations.

- Spoliation. In the age of computers, e-mails, text messages, computer files and other electronic data are easily created and easily deleted. Once litigation is threatened or pending, parties and witnesses should take action to preserve evidence, including electronically stored information for potential use in the lawsuit.

- Motions to Compel. Lawyers must make reasonable efforts to resolve disputes over the legitimacy of objections, the sufficiency of responses and other discovery disputes without putting it before a judge. When disputes cannot be resolved, typically one party will bring a motion to compel discovery against the other.

- Sanctions. The failure to obey discovery orders can subject a party to a variety of sanctions, including awards of attorney’s fees, dismissal of claims or defenses, exclusion of witnesses and other punishments.

By better understanding the basics of civil litigation discovery, one can adopt strategies that make better use of time, energy and resources pre-trial. Implementing discovery strategies proper to the needs and circumstances of the case pave the way towards a favorable result.

January 29, 2015

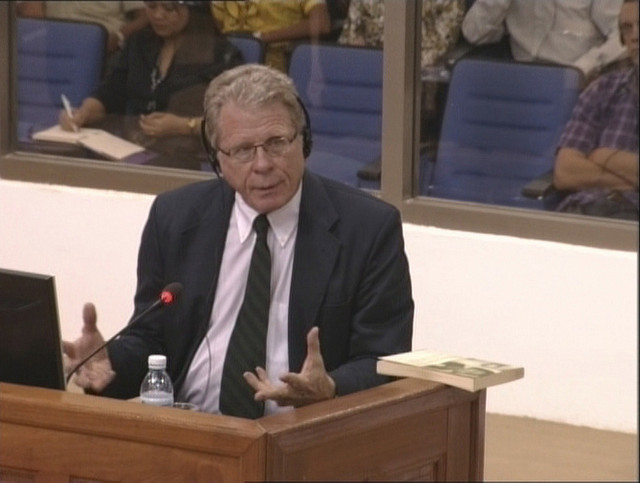

New Book Review: The Articulate Witness

One of the duties of a litigator is to prepare the client to testify at a deposition, mediation, hearing or trial. Clear, credible and cogent testimony puts the party in the best position to prevail. While judges, arbitrators and juries want to see the contracts and key documents, they also want to hear directly from the parties whose dispute is before the court.

Experienced trial attorneys know what to expect of themselves and their witnesses from the facts of the case. When it comes to public speaking, witness preparation typically includes discussion of the disputed facts and legal arguments in the case. While an attorney may not tell the client or witness what to say, he may ask practice examination questions. Witnesses quickly learn that courtroom or deposition testimony differs from ordinary conversation or interviews. A witness may have little or no public speaking training or experience. There may not be time for a witness to gain valuable experience in Toastmasters International or other activities to practice speaking skills. So how can a witness prepare herself to give effective testimony in her own case?

This month, Brian K. Johnson and Marsha Hunter published a new book, “The Articulate Witness: An Illustrated Guide to Testifying Confidently Under Oath.” This edition is available in print or e-book format. Johnson & Hunter are consultants who train attorneys for a variety of public speaking settings. I have read one of their other books and attended one of their seminars. “The Articulate Witness” is useful to parties and witnesses seeking an overview of the legal testimonial process. It is a valuable resource for attorneys and law students seeking insights in how to better prepare their clients to testify. Professional experts evaluating their own habits and skills would benefit as well. The book is a breezy 50 pages with copious illustrations. I finished it riding on the D.C. Metro between the Judiciary Square & West Falls Church stations. The book focuses on the mechanics of speaking confidently in litigation situations, including cross-examination. The book would be useful to a witness when they first know that a deposition, hearing, trial, etc. will occur. It is not a good book to read the evening before the big day. The reader may desire to practice some of the exercises or discuss them with the attorney beforehand. The book is not a proper substitute for trial preparation with one’s attorney.

A common mistaken belief is that public speaking involves only expressing one’s thoughts using one’s voice. Johnson & Hunter do a great job of showing how it is also a “physical” activity, involving posture, gestures, handling exhibit documents, facial expression and eye contact.

“The Articulate Witness” is an excellent reference for witnesses,attorneys, experts or any other person whose profession or circumstances require him to speak in a legal proceeding. Mastery of the facts and laws is not sufficient. One must be prepared to cogently communicate one’s position to others.

photo credit: Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia via photopin cc

March 20, 2014

“Is This a Film?” Video Within Video in the Justin Bieber Deposition

How is technology used in deposition and trials? Last week I attended Technology in Fairfax Courtrooms: Come Kick Our Tires!, a Continuing Legal Education seminar sponsored by the Fairfax Bar Association. This program interested me because real estate and construction cases are rich in photographs, plats, large drawings, sample construction materials and other visual evidence. Courts across Virginia are installing high-tech equipment for use in presenting pictures, video, audio and other media in trials. This seminar is a useful overview of the technological sea change in trial practice, including presenting audio and visual recordings of depositions at trial.

The credibility of a party’s testimony is at the heart of any trial. Sometimes parties and other witnesses will change their testimony. Lawyers use deposition records to test credibility on cross-examination. A video or audio recording can recreate the deposition vividly for the jury. Impeachment by video is not a feature of most trials because of significant time and expense associated with use of the technology.

At the courtroom technology seminar, someone mentioned pop music superstar Justin Bieber’s March 6th video deposition. This video leaked to the news media. The lawsuit alleges that Mr. Bieber’s entourage assaulted a photojournalist. I usually avoid following the news about celebrities’ depositions. I am familiar with the usual witness behavior. I’ve taken depositions of parties, experts and other witnesses. A celebrity may not be any more prepared for a deposition than an ordinary person. I watched excerpts of the Justin Bieber deposition on YouTube to see if it illustrated any new strategies.

In one excerpt, attorney Mark DiCowden shows a video of a crowd of people next to a limousine. Mr. Dicowden asked Bieber to look at the “film” on a screen behind the witness. The witness glances at the screen, turns back to DiCowden and evasively responds, “Is this a film?” DiCowden tried to focus Bieber on the video to establish a foundation for questions. As a viewer, I struggled watching the screen within a screen while following the examination. To capture Justin Bieber’s interaction with the video, the court reporter zoomed out, making both the video and Bieber smaller. If counsel tried to use this at trial, I imagine the jurors, sharing monitors, would struggle with this as well, with the added distraction of live court action. Justin Bieber’s evasive remarks and body language stand out here in what might otherwise be a disjointed use of technology. Since only excerpts are available, it is difficult to determine whether he went on to actually answer substantive questions about the video.

I wonder whether Plaintiff’s decision to incur the expense of this video deposition (and any related motions) will ultimately be useful for settlement or resolving the case in the courtroom. How will the deposition record look to the jury weighing the credibility of the witness? The Justin Bieber deposition provides some insight into use of video exhibits within a video recorded deposition. Getting an adverse witness to alternatively focus on questions and a video playing behind him is a challenge.

Even if your case does not involve celebrities, a practice run helps to prepare you for a video deposition. For example, the attorney taking the deposition could experiment with different layouts for the camera, people, screen and other visual exhibits to see how they look on replay. On the other side, the witness may learn something from viewing a video of himself answering practice deposition questions. Retain a lawyer with trial and deposition experience with evidence similar to your dispute.

featured image credit: Steven Wilke via photopin cc