January 24, 2014

Title Litigation: Centenarian Deed Decides Methane Royalty Rights

On January 10, 2014, the Supreme Court of Virginia decided CNX Gas Company, LLC v. Rasnake, interpreting disputed language in a 95-year-old deed. The Court determined who owned the mineral rights in a parcel of land in Russell County in Southwest Virginia. The contested deed contained both (a) words conveying a parcel and (b) limiting language that excepted certain property from the transaction. Ultimately, the words of conveyance prevailed over the words of limitation! The opinion is a useful collection of some of the rules about how to prepare, interpret or litigate a deed.

In 1887, Jacob & Mary Fuller conveyed the coal in a 414 acre tract in Russell County to Joseph Doran and W.A. Dick. In 1918, W.T. Fuller conveyed to Unice Nuckles a 75 acre portion of the Fuller family tract except that, “[t]his sale is not ment (sic) to convey any coals or minerals. The same being sold and deeded to other parties heretofore.”

Over 90 years later, CNX Gas Company holds a lease from the successor to Ms. Nuckles for the mineral rights (excluding coal) in the 75 acre tract. CNX produces coalbed methane from the parcel. Coalbed methane is a natural gas extracted from coal mines and sold as energy. The opinion does not discuss how methane is a “mineral.” The parties likely stipulated to that based on authorities not mentioned. The successors to W.T. Fuller sue CNX over the non-coal mineral rights. To resolve the dispute, the Court has to decide what the above-quoted language meant. Have the non-coal mineral rights been legally conveyed or not? Royalties to the coalbed methane hang in the balance.

When I initially read these facts, I wondered if perhaps I was missing something. Did the 1887 deed say something about non-coal minerals? Was there some other deed prior to 1918 conveying the minerals? Perhaps there was an unrecorded deed known to the parties in 1918. Since the opinion states the parties stipulated to the facts, the title examination must have revealed the answer to both questions to be “no.”

The Supreme Court of Virginia applied the following legal rules to resolve the title dispute:

- Is the language capable of being understood by reasonable persons in more than one way? One could assume the answer to be “yes,” since the issue found its way to the highest court in the Commonwealth. But lawyers have a reputation for torturing unambiguous language, so the question is appropriate. The Supreme Court found the deed ambiguous.

- Which interpretation favors the grantee (recipient)? Since the Grantors (usually sellers) are the ones who sign the deed conveying the property, it is only fair to assume that they chose their language carefully.

- Can the language of the deed be considered holistically? Since W.T. Fuller included all of those phrases in the deed, it is reasonable to harmonize them rather than pick and choose certain sections that favor one side over the other.

- Is the limiting language clear and unequivocal? A deed must have, among other things, words of conveyance, which generally describe the lot or parcel of land transferred. A deed may also include other language limiting or reserving certain interests excepted from the transfer, such as certain mineral rights. Unless the limiting language contrary to the general grant is expressed clearly and unequivocally, it will not be upheld in court.

The Supreme Court of Virginia applied these rules to find that the only “coals or minerals” not included in CNX’s leasehold interest are the coal rights conveyed to Joseph Doran and W.A. Dick in 1887. The Court entered judgment upholding CNX’s rights to extract the coalbed methane from the 75 acre tract. Words of conveyance prevailed.

P.S. – There is one other principle that the Court could have mentioned: when interpreting legal documents, the specific prevails over the general. Since the 1914 deed made reference to previous conveyances of natural resource rights, the plaintiffs’ stipulation to the absence of any other deeds locked them in.

January 13, 2014

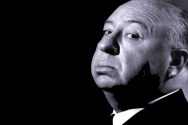

Reel Property: Hitchcock’s Skin Game

A working-class family is wrongfully evicted from their rental homes and may lose their jobs. A neighboring landowner and his shrewd agent try to stop the sharp-dealing landlord from destroying property values with industrial air pollution. Can they successfully escalate conflict without unintended fallout?

This is the subject of Alfred Hitchcock’s early film, “The Skin Game” (1931). The Skin Game is based on a play by John Galsworthy, a British lawyer who found a second career as a writer. Mr. Hillcrist (C.V. France) is an old-money landowner at odds with Mr. Hornblower (Edmund Gwenn), a nouveau-riche industrialist. Hillcrist objects to Hornblower’s purchase of neighboring pristine countryside for the construction of new smoke-belching factories. The two battle over competing visions for the Deepwater community in a series of increasingly sharp business practices. The Hillcrests’ agent, Mr. Dawker (Edward Chapman) plays an easily overlooked role in this dark comedy.

Jocelyn Codner observes in her blog, The Hitchcock Haul, that The Skin Game speaks to contemporary controversies surrounding land use, fracking and class warfare. Contemporary audiences may identify with the film in additional ways. The Skin Game’s audience remembers the horrors of global war. Worldwide recession brought high unemployment. Fear and desperation hide in the film’s shadowy scenes. These emotions unfold in total war between the neighboring landowners with tragic, unintended consequences. Tenants’ and neighbors’ rights versus job creation.

The aggressive business practices in the movie are frequent, rash and ill-considered. I found myself counting all of the legal claims and defenses that could potentially be brought in Court (this post makes no effort to interpret the facts under 1931 British law). Spoilers follow, but they are 83 years in the making!

- Violation of Covenants. In order to build new factories, Mr. Hornblower violated a covenant he made to Hillcrist when he turned out long-standing residential tenants. In Virginia, that would likely unfold as a contested unlawful detainer (eviction) action. Since the parties did not end up in Court, I assume that the Hillcrists failed to make the covenant legally enforceable.

- Bid Rigging. A mutually coveted parcel of land goes to a public auction. Ominously, the auction house’s lawyer reads the conditions of sale so softly that only the front row can hear. The Hornblowers and Hillcrists bid in concert with their own secret bidding agents to confuse their opponent and hike the price. Hornblower wins. Hitchcock uses quick camera work and multiple angles to build suspense and simulate confusion.

- Fraud. Hornblower’s daughter-in-law Chloe (Phyllis Konstam) has a secret past that includes employment by men to help them secure divorces premised upon adultery. This doesn’t come up much in the era of non-fault divorce, but giving false testimony for hire is sanctionable.

- Conspiracy. The Hillcrists’ estate agent, Mr. Dawker discovers Chloe’s past from her former client. Mrs. Hillcrist and Mr. Dawker decide to use the secret to extort Mr. Hornblower into selling them the contested parcel at a loss. The parties anticipated that disclosure of the secret would destroy Chloe’s marriage with the young Hornblower. The consideration of a sale from Hornblower to Hillcrist consisted of both (a) a written contract for cash and (b) a secret unwritten agreement not to reveal Chloe’s past.

- Breach of Contract: Upon pressure by the young Hornblower, Mr. Dawker violates the secret unwritten non-disclosure agreement and likely his fiduciary duties to the Hillcrists.

- Professionalism. In contemporary transactions, one would expect Mr. Dawker to be a licensed real estate agent. His role in the bid rigging and the conspiracy would potentially expose him to disciplinary action by the Real Estate Board.

- Assault. In a fit of rage, Mr. Hornblower throws his hands on Mr. Hillcrist’s neck.

- Defense of Unclean Hands: Although the evicted tenants temporarily get their cottage back, this victory falls flat because of the greater tragedy which brings Mr. Hillcrist remorse. Unclean hands foul the initial nobility of their cause.

Was there a moment when a more trusted advisor, be it a realtor, attorney, or friend, could have helped Hillcrest settle the dispute? The loud passions of the warring families obscure Mr. Dawker’s fateful role as agent in the “Skin Game.” In the final scene, loggers chop down one of the Hillcrists’ oldest trees. What goes around, comes around.

January 2, 2014

Can My Landlord Evict My Business Without Going to Court First? – Part II – Complications to Landlord Self-Help

In Virginia, landlords have a right to evict commercial tenants without going to Court first. This does not make it likely or wise. Even in jurisdictions where self-help is legal, it is unusual to see landlords piling up their tenants’ business property on the curb. There are several reasons why:

1. Lease Terms: Any self-help must comply with the terms of the lease agreement. The laws of Virginia and its neighbors vary regarding a landlord’s remedies upon the tenant’s default. Many commercial leases are forms adapted from use in other jurisdictions. These forms may be a challenge to interpret under Virginia law. Even terms drafted with an eye to the law of the jurisdiction may not contemplate the exercise of the self-help remedies desired by the landlord’s agents. The terms of some lease agreements eliminate the right of self-help eviction entirely. Many other leases do not clearly define the landlord’s rights to exercise self-help. When parties negotiate the lease agreement, tenants typically request that any detailed landlord self-help eviction terms be edited out. The landlord often finds himself reserving, in a general way, its common law remedies, including self-help, without defining how they may be exercised. When the issue comes up upon default, both parties experience uncertainty regarding how a court would view the landlord’s threatened action.

2. Possibility of Property Damage: The landlord may be averse to taking possession of the property in a way that may damage the tenant’s property or involve physical confrontation with the tenant’s personnel. The landlord may desire an award or settlement for the balance of the lease. Property damage counterclaims complicate collection efforts.

3. Forcible Entry Claims: In certain situations landlords and tenants may be punished criminally under forcible entry, detainer or trespass for aggressive action taken with respect to the premises and business property in dispute.

4. Bankruptcy Stay: If the tenant is in bankruptcy, then an automatic stay likely prohibits self-help. The dispute between the landlord and the debtor-tenant over rights to possess the space is addressed in federal bankruptcy court.

5. Sublease: The landlord-tenant relationship may be complicated by a subletting arrangement. A sub-landlord and the master-landlord may disagree regarding their respective rights to possess the sub-leasehold. Disagreements between the property manager and the sub-landlord may delay action.

6. Institutional Landlords: The organizational structure of the landlord may play a role. When the same individual is the owner and property manager of the building, that person will likely exercise broader discretion than in a more institutional context.

These issues do not necessarily preclude the use of self-help. A risk-adverse landlord may view going to court to gain possession as a desirable alternative.

What should a tenant do if the landlord is threatening to take possession prior to going to court? The simplest options are to (a) avoid falling into default or (b) plan a move-out in advance if a default appears imminent. In certain situations, the circumstances of the business or relationship with the landlord may be too complex or attenuated for that. The tenant may have business operations or valuable property to protect. In any case, careful consideration of the lease terms and cogent communication with the landlord are essential. Where property and income are at stake, potential risks associated with changing locks and removing property are too great for either side to view landlord self-help as the logical first step towards resolving a dispute. In these situations, a tenant is best served by interacting with the landlord through experienced brokers and lawyers.

photo credit: vasilennka via photopin cc